How Obama is helping inmates pay for college

Despite a 22-year ban on financial aid for the incarcerated, Obama launched a pilot program to connect as many as 12,000 inmates to federal scholarships starting next month.

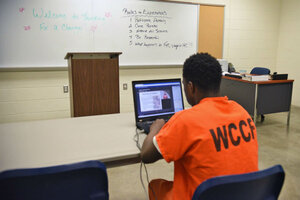

An inmate takes a class toward earning a high school diploma at the Washington County Correctional Facility in Pennsylvania, where state law and federal law entitles inmates under 21 to a free public education. This week Obama launched a pilot program to help connect inmates with higher education in partnership with 67 US colleges and universities.

Celeste Van Kirk/Observer-Reporter/AP

Starting next month, thousands of US prison inmates will be able to access federal financial aid to continue their higher education studies.

These new students, which could number up to 12,000, will remain in their prison facilities learning through online classes, classroom-based instruction, or a combination of the two, reports the Washington Post. But the Obama administration hopes that the pilot financial aid program will open doors for the inmates when they leave the system.

“We all agree that crime must have consequences, but the men and women who have done their time and paid their debt deserve the opportunity to break with the past and forge new lives in their homes, workplaces and communities,” Education Secretary John B. King Jr. said on a call with reporters Thursday. “This belief in second chances is fundamental to who we are as Americans.”

The pilot program is part of a larger, bipartisan effort to reform the US justice system. It includes measures ranging from "ban the box" so felons don't have to report criminal history on job applications to rolling back lifetime sentences on drug-related crimes and commuting the sentences of low-level and nonviolent drug dealers.

The Second Chance Pell Pilot Program will enable inmates to access Pell grants, which are federal education scholarships of $5,815 or less per year. By slating this as a trial, the US Education Department can circumvent a 1994 Congressional ban on awarding Pell money to inmates. The trial has been over a year in the making: last summer the Obama administration publicly announced the executive action to launch the program in 2016.

At the time, Republican Rep. Chris Collins, filed his own bill, the "Kids Before Cons Act," which would study whether students enrolled at charter or private schools under a voucher program are less likely to end up in prison than children in traditional public schools. The idea behind the Collins bill: Reduce imprisonment on the front end, rather than spending money on the back end.

“The Obama administration’s plan to put the cost of a free college education for criminals on the backs of the taxpayers is consistent with their policy of rewarding lawbreakers while penalizing hardworking Americans,” Collins (R) of New York told Politico.

The Obama initiative brings together more than 100 federal and state adult penitentiaries and 67 colleges and universities, the majority of which have offered some version of prison-based education in the past, according to the Washington Post. Inmates must be within 5 years of leaving prison in order to access the funding.

In 1994 when Congress voted to stop the funding, as part of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, there were 25,168 inmates using the funding for higher education, who made up 1 percent of all grantees, reports the Post. The vote was part of the stringent criminal justice policies that were put in place in the 1990s and under President Bill Clinton, who signed the ban on Pell grants for inmates, after Congress decided roughly 3 to 1 that the money shouldn’t be used for inmates when other citizens were struggling to pay for higher education.

But there has been much criticism of the zealous criminal justice measures taken during that era, even by Mr. Clinton himself, and there's a shift underway to find a better model.

The Pell funding trial reflects a broader national conversation about how to improve the corrections system and the transition of inmates back into society after incarceration.

“Definitely I think there is a movement to reconsider what is being done within correctional facilities and to expand the opportunity for rehabilitation through college-level education,” John Dowdell, co-editor of The Journal of Correctional Education and director of the Gill Center for Business and Economic Education at Ashland University in Ohio, told The Christian Science Monitor’s Harry Bruinius earlier this year.

And the benefits of rehabilitation through education have been born out in the research.

In a federally funded 2013 study by the RAND Corporation, research showed that inmates who took part in correctional education programs had “43 percent lower odds of returning to prison than those who do not,” and that the inmates who participated in either academic or vocational programs had a 13 percent higher employment rate when they left prison than those who did not.

“Our findings suggest that we no longer need to debate whether correctional education works,” said Lois Davis, the project's lead researcher. “But we do need more research to tease out which parts of these programs work best.”

There are many such programs already in place across the United States. Bard College, for example, offers tuition-free degrees for inmates as part of the 15-year-old Bard Prison Initiative, which awarded 300 degrees in in 2013. Students from the initiative made national news last fall when their debate team, made up of three students from Eastern New York Correctional Facility, beat Harvard University’s team in a match, reports the Monitor’s Patrick Torphy.

The success of the 12,000 students expected to benefit from the Second Chance program's Pell grants will be watched in the coming years, and could influence whether Congress decides to lift the ban and expand access to more of the nation's inmates.