How to free modern slaves: Three tech solutions that are working

From satellite surveillance of illegal fishing boats to online sleuthing into recruitment practices, activists are finding new ways to fight back. Part 5 of a series on human trafficking.

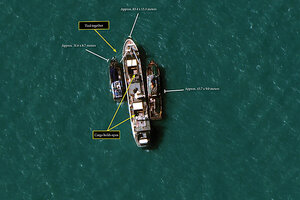

A high-resolution satellite image of the Silver Sea 2 that shows a transshipment with two slave fishing boats off the coast of Papua New Guinea.

Courtesy of DigitalGlobe

This story was designed to be read on the Monitor's long-form platform.

The WorldView-3 satellite is powerful enough to spot a manhole from 380 miles above the Earth’s surface. So taking high-resolution shots of a 266-foot refrigerated cargo ship should be a routine job.

The hard part for DigitalGlobe, a Colorado-based commercial vendor for space imagery, was finding the reefer. But once it was spotted in the South Pacific anchored off Papua New Guinea, the satellite hurtled into position. The image it captured on July 14 confirmed what investigators had feared: the ship was receiving slave-caught fish from illegal trawlers.

“We were able to very clearly see the fishing boat with the two illegal trawlers up against it,” says Taner Kondanaz, director of DigitalGlobe’s “Seeing a Better World” program, adding that their cargo holds were open. “That was irrefutable evidence.”

Evidence is what law enforcement needs to go after the perpetrators of modern-day slavery. In this case, though, it wasn’t a police unit behind the camera but a team of investigative journalists at The Associated Press. Photographing the trawlers offloading their catches onto the reefer was a key moment in its months-long investigation into human trafficking on the high seas.

The two trawlers were known to have slave laborers onboard, while the reefer, the Silver Sea 2, was found linked to the supply chains of major American food sellers. The AP’s work has led to the release of more than 2,000 fishermen and fueled protests over the business practices of companies including Walmart, Sysco, and Kroger.

The AP investigation has since wound down, but its innovative use of global tracking and satellite technology has caught the attention of anti-trafficking advocates and government officials. It was the first time a high-resolution satellite camera had been used to capture human trafficking in action.

The operation’s success provides a glimpse of the potential for technology to aid in policing the vast and lawless ocean. Finding a way to efficiently replicate it, in addition to developing newer technologies, could help free the thousands of fishermen held in captivity on the open seas – and expose other abuses in global industries like fishing.

“What happens on the ocean is largely out of sight and out of mind,” says Karen Sack, managing director of Ocean Unite, a nonprofit group focused on sustainable fishing and marine conservation. “These technologies can help shine a light on its darkest corners.”

Eyes in the sky

Monitoring the ocean, which makes up 71 percent of the Earth’s surface, has long been a daunting task. A lack of resources and political will has turned huge swathes of international waters into a modern-day Wild West, where illegal fishing and forced labor often take place with impunity.

“The outlaw ocean results from a void of jurisdiction,” Robert Stumberg, a Georgetown University law professor, said at a briefing for the Senate Caucus to End Human Trafficking in Washington on Sept. 29.

Professor Stumberg says the evolution of technology can create a momentum of its own as public awareness about slave-caught seafood grows and policymakers begin to take notice. Advancements in satellite imagery, remote sensing, and digital mapping promise to improve enforcement and transparency in seafood supply chains.

“There are six degrees of separation between the buyer on one end and the boat that’s using slave labor on the other end,” he says. “Anything that can help connect the dots is helpful.”

At the request of the Senate caucus, Stumberg analyzed $300 million worth of government purchases of fishery products that he says were most likely produced by slave labor. He concluded that the more information gets added to the federal spending database, the better equipped the government will be to make informed buying decisions.

Outside of government, one of the most ambitious initiatives launched in recent years is Global Fishing Watch, an online platform that uses satellite data to visualize commercial fishing activity worldwide. The program’s primary target is illegal fishing, but its developers say it has the potential to help track slave fishing ships once it’s made publicly available next year.

“The data and technology exist right now to track individual vessels,” says John Amos, president of SkyTruth, an environmental watchdog group that’s helping to build Global Fishing Watch and assisted in the AP investigation. “You just need to know you’re interested in them.”

Beyond sea slaves

As awareness about human trafficking grows, advocates are looking for ways to expand technological capabilities to take on the problem in its many forms, including trafficking in the fishing industry. The International Labor Organization estimates that 14.2 million people are victims of forced labor in private economic activities. Only a fraction of them are forced to work on fishing ships on the high seas.

For its part, DigitalGlobe, the commercial satellite operator, has extended its humanitarian surveillance program to monitor suspected slave-operated brick kilns in India and fisheries on Lake Volta in Ghana.

Even the US government is pushing for new technologies. On Oct. 28, it launched a competition to find new high-tech solutions to labor trafficking in global supply chains in partnership with Humanity United, a Washington-based nonprofit organization. The grand-prize winner will be announced in April and awarded $250,000 to build a late-stage prototype of its design.

“There’s been a shift in the way that major corporations are thinking about what they need to do to tackle forced labor in their supply chains,” says Catherine Chen, director of investments for Humanity United. “There’s a really unique opportunity here.”

* * * * *

During World War II, US scientists imagined a hypothetical analog computer that would supplement the human brain. They called it Memex, a play on the words “memory” and “index.”

Last year, the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, announced the launch of a new program of the same name that could fundamentally change the way people gather information from the Internet.

Memex, in its modern iteration, is a tool for scanning the hidden corners of the World Wide Web, and for connecting bits of information that have long proved elusive for investigators. And developers, prosecutors, and advocates say it can be a powerful tool for exposing and uprooting human trafficking, which thrives in dark corners.

“The technology can provide a help here for finding the answer,” says Wade Shen, program manager at DARPA’s Information Innovation Office. “We can raise the price on this. We can make it harder for it to happen.”

To understand what Memex does, and how it could aid human trafficking investigations, start with the Web itself and the way most people use it.

When the average person goes online, he or she types a few words into a search engine such as Google. Those search engines then do a split-second sweep of a vast informational index; data that the search engine has already collected, parsed, and stored.

These indexes are spectacularly broad, since they are meant to provide quick information in response to any possible query. But they are not particularly deep. In other words, there is a lot of information on the web that will never come up in a Google search.

Some of it is content that commercial search engine crawlers are just not good at picking up, such as a changing menu on a restaurant website. But it also includes content that is hidden on purpose: the “dark web.” The dark web is an intentionally anonymous Internet, built on top of the existing Internet structure but without the markers of source and destination addresses that leave a fingerprint with every search.

Free speech and illegal drugs

The dark web, many advocates say, plays an important role in global free speech. Activists in repressive countries, for instance, can use it to connect with one another without risk of being discovered. Journalists can get past censorship rules. Whistleblowers can leak information about their companies without worrying about retribution.

But it is also a haven for criminal activity. On the dark web, marketplaces exist for everything from child pornography to illegal guns and drugs to sex trafficking. Silk Road, for instance, a black-market website that the FBI shut down in 2013, earned tens of millions in commissions for its operator.

Memex helps investigators open up the entire web – light and dark – by letting them access information in its hidden regions, and by cataloging that information in a way that finds patterns between sites. These patterns are crucial to making sense of the data. Investigators can scan a huge number of dark web prostitution adds and build links between them based on phone numbers or particular images – aspects that would be difficult to categorize using commercial search engines. (They might be able to connect seemingly unrelated sex advertisements, for instance, by locating the same woman in photographs.)

“When sex traffickers create online ads for their victims’ sexual services, they leave a digital footprint that leads us to their criminal activity,” said Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. in a press release earlier this year. His office says it is using Memex in numerous sex trafficking investigations – including a case late last year in which a man was sentenced to 50 years to life in prison for kidnapping a 28-year-old woman and forcing her into prostitution.

“Because those ads are frequently removed or intentionally hidden on the ‘dark web,’ it puts them beyond the reach of typical search engines, and therefore, beyond the reach of law enforcement. With technology like Memex, we are better able to serve trafficking victims and build strong cases against their traffickers,” says Mr. Shen.

Scaling up the solution

Now Shen and his colleagues at DARPA want to figure out how Memex can best help combat the broader crime of labor trafficking.

“It’s a bit of a different story,” Shen says. “Unlike with sex trafficking, the product is not directly advertised on public forums. So one of the things we’ve been looking at is, where is the publicly visible point in this supply chain?”

One idea is to scan websites where migrant workers can give feedback on their experiences with recruiters and US employers. Memex might be able to connect these reports with job advertisements or placements in the US in order to trace anonymous claims of abuse.

The program might be able to dig up leads by analyzing hiring patterns in different parts of the country. Investigators could also track down suspicious “help wanted” ads that are posted in the wrong region or on low profile websites – a possible indicator of an unscrupulous employer trying to prove that they tried and failed to hire Americans, thus opening the door to hire migrants with temporary work visas.

“With Memex we can start to allow investigators to look within a space to track and trace the movement of goods,” Shen says. “In all of these trafficking scenarios, the question is how do you attack the supply chain? How do you get at the movement of goods and where they end up?”

* * * * *

MEXICO CITY – It wasn’t until José arrived on the job site in New York that he realized he’d been duped.

The high-paying construction job promised in 2007 by a crooked recruiter in Mexico ended up being an underpaid and abusive carnival gig.

“When they told us the job was now the fair, paying much less, they said, ‘You are here for work. If you have a problem, go back to Mexico,’” José says. He’d paid over $1,000 in upfront fees to secure the job, and going home in debt wasn’t an option, even if it meant working 20-hour shifts and being barred from leaving the carnival grounds.

Back in his small town in central Mexico, José tells everyone who asks that there’s a way to avoid being sucked into modern-day slavery, as he was. He encourages them to use a website, Contratados.org, that allows migrant workers to anonymously rate, review, and research companies and recruiters – essentially a Yelp for migrant workers.

The website, launched a year ago by the Centro de los Derechos de Migrants (CDM), an advocacy group, asks temporary workers in Mexico traveling to the US on visas to share their experience – good or bad. The goal is to shine a light on bad practices so that workers can avoid being abused or trafficked.

Under the guest worker program, recruiters and employers hold most of the cards. Recruiters choose who they will hire or leave behind, and workers are bound by their visas to their employers. That makes it all the more essential for workers to know who is playing by the rules and who is to be avoided.

More than 140,000 Mexicans traveled to the United States as guest workers last year. It’s illegal in both countries for recruiters to charge fees, but many do. In a 2013 survey, CDM found that nearly 60 percent of workers said they had paid money upfront to a recruiter.

“The more information that’s out there, the better,” says Jennifer Gordon, a law professor at Fordham University in New York who has written extensively on global labor recruitment. And the key is connecting that information to the workers, she says.

Not all temporary workers are literate or have regular access to the Internet, so Contratados.org also accepts reviews via text message and telephone. CDM staffers transcribe the messages and vet the reviews before posting for identifying information.

Reluctant reviewers

Some migrants are reluctant to write a review – even if the post is anonymous – for fear of reprisals by future recruiters or employers. It often requires a prod from CDM to overcome this fear.

A young woman who asked to be identified by her initials, BRS, says she wrote her review both to warn other migrant workers and to have her own voice heard. When she was 24-years-old, she went to New York to work as a nanny, paying $1,500 upfront. The company that contracted her pulled her out of its training classes on her first day, saying she’d not disclosed a terminal illness. BRS denied the claim, but the employer sent her home and kept most of her deposit. When she applied to another company using her existing visa, the company declined to hire her because they’d heard about her “reputation.”

“I wrote my review because it’s important to raise your voice to tell your side of a story, especially when it seems like no one official will listen,” BRS says. “If someone sees my experience it might make them consider things a little harder.”

In its first year, Contratados.org tracked visited from nearly 400,000 people, and reviews included experiences of physical, verbal, and sexual abuse, poor housing conditions, and withheld wages. The project is funded by grants, though CDM hopes to license versions of the platform to transnational advocacy groups in other regions, such as Southeast Asia.

José would like to return to the US on another work visa since he can’t pay off his debt from New York on the roughly $80 per week he makes in Mexico.

“I’ll do my research with this tool,” before signing on with another recruiter, he says. “But the truth is, we want to work. At the end of the day we want to go legally to the US and work.”

Nov. 16: In Florida's tomato fields, a movement toward ethical labor grows.

Nov. 9: From England's pews, a quiet abolitionist finds his voice on slavery

Nov 2: One woman's journey from Staten Island slavery to being her own boss.

Oct. 26: Modern slavery: Labor trafficking is everywhere and nowhere