In Trump win, Europeans see threat to 'bedrock' transatlantic values, ties

Commentary: The unexpected victory has shocked capitals, which are shifting from chronic crisis management to acute damage control.

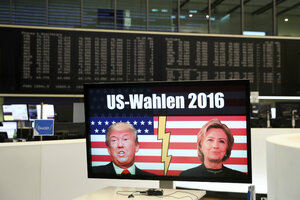

A TV screen showing US President-elect Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton is pictured at the stock exchange in Frankfurt, Germany, Nov. 9, 2016.

KAI PFAFFENBACH/Reuters

Berlin

Dismay swept Europe as American voters selected reality-TV tycoon Donald Trump as the next American president – and put his restless finger rather than Hillary Clinton’s steady hand on the nuclear button.

The first German government official to comment on Mr. Trump’s upset, Defense Minister Ursula von der Leyen, called the win a big shock, nudging the president-elect to drop the isolationism he has preached, and pointedly asking what his intentions are on NATO and on Russian President Vladimir Putin, whom Trump has singled out for praise for his alpha-male leadership.

Already, the Europeans are shifting down from chronic crisis management to acute damage control. They will try to salvage as much as possible of the transatlantic relationship that has been the bedrock of the West in preserving liberal values and shaping open international institutions in the post-World War II world. In an era when democracies feel especially besieged by a rising, assertive China and a declining, and therefore defiant Russia, they will seek to stabilize a Europe in flux.

At a time when centrist parties have shrunk across the continent, the Europeans will strive to minimize the impetus that Trump’s nativist triumph gives to Europe’s own jubilant populist parties. And they will try, somehow, to regain the trust of all the losers in their own domestic constituencies who feel excluded from the general prosperity in the technological disruption and influx of Middle Eastern, Asian, and African refugees, whom they blame for stealing jobs from them.

Along the way, European officials will mourn the failed candidacy of Hillary Clinton, who embodied the continuity they had hoped for in the West’s leading democracy. They knew her well from her three decades in the public arena. She prepared for the presidency with detailed policies drawn up by large teams of senior advisers whom European officials have mingled with over decades. She worked hard as secretary of State on the trade agreements that Trump wants to rescind – and that Europeans deem essential if the West is not to repeat the beggar-thy-neighbor protectionism that led to the depression of the 1930s. Her blend appealed strongly to conservative Europeans, who wanted to perpetuate the post-1945 European Community system under US patronage that finally seemed to have banished war on one of the bloodiest continents in history.

By contrast, few European officials know Trump personally. They can judge him only through his anti-elite insurgent campaign in which he cast doubt on longstanding American commitments to defend allies, preached both economic and geopolitical neo-isolationism – and praised as his own strongman idol Vladimir Putin, who shattered heartland Europe’s longest peace in history by launching an undeclared war on Russia’s independent neighbor Ukraine in 2014.

Even fewer European officials know Trump second-hand through his advisers. The president-elect, regarding foreign-policy experts as members of the establishment that he has now swept aside, sees little need for banks of consultants; he trusts his own instincts. On being told by one adviser that America stocks apocalyptic nuclear weapons with no intent to use them except as a deterrent, he protested and asked why the US shouldn’t use them if it possesses them. The alarm this raised among senior military officers with nuclear responsibility gave rise to black jokes about how they might have to save the world by ripping the launch code out of the nuclear football.

It would thus be hard to exaggerate the dread of a Trump victory among both European elites and populaces. In Germany, the continent’s largest and most influential country, some 73 percent supported Clinton and 80 percent thought that a Trump victory would hurt transatlantic relations, according to Forsa and ZDF TV opinion polls just days before the election.

Even these high negatives don’t begin to express the angst in Europe about Trump, as felt most viscerally by Germans haunted by their nation’s history of succumbing in the 1930s to a Führer whom they initially scorned as a clown.

Brookings Institution Fellow Constanze Stelzenmueller – a German who since childhood has admired the America that rescued Europe and the Germans from the atrocities of Hitler, from post-World-War-II devastation, and from the threat of the 20-plus Soviet divisions that stayed on for half a century after the war in (eastern) Germany – expressed her foreboding about “this dystopian US election” most trenchantly. She noted Trump’s Star of David tweet, which “would have meant instantaneous, irredeemable disgrace” in today’s Germany but was hardly noticed in the US. And as a Harvard-trained student of the US Constitution and rule of law, she deplored Trump’s broad hints to his supporters to use their guns on Clinton or “lock her up.”

“If it can happen here [in America], it can happen anywhere,” she worried. “Certainly what sets Trump apart from any major US politician – let alone presidential candidate – in living memory is his overt, chilling contempt for the fundamental principles of the Constitution. That is familiar to a German in the worst possible way.”

Geopolitically, the European Union must now go beyond its trademark soft power to take over Washington’s three-generation-long security guarantee of Europe, even as that American commitment fades. It must expand the leadership of Chancellor Angela Merkel in calling Putin’s bluff and containing a Russia that is far weaker than the old Soviet superpower but tries to compensate domestically for its plummeting health, educational, and living standards by nuclear saber-rattling and bellicose military gambles in Ukraine and Syria.

Back in 2014, Ms. Merkel was the one who stated immediately that Russian annexation of Ukraine was an unacceptable violation of international and treaty law, told powerful German businessmen that they must subordinate their Russian profits to respect for rule of law, and pushed unanimous financial sanctions on Russia – which remain in place – through the EU. She is said to be the one European leader Putin does not consider weak and the one he most wants to unseat.

In the case of Ukraine, Merkel first saw herself as only a temporary placeholder of Western power until such time as the US might reengage in Europe. The Trump victory and US isolationism, however, now make her the default long-term leader on the continent.

On the European level, member states must hold the European Union together after the United Kingdom’s casual Brexit referendum pulled the plug on British membership last summer and upset the internal balance that in the 1950s solved the 150-year-old “German question” by embedding Europe’s most dynamic nation in a peaceful integrated Europe.

The EU and its member states must rebuild domestic community trust at a time when that stupendous 1940s restoration of peace is only a faint memory for generations who have never known war. More broadly, it must regain its sense of identity and confidence in a post-liberal era when Russian, Chinese, Turkish, and Hungarian governments are hailing authoritarianism as the corrector of capitalism’s flaws – and a new, autocratic end-of-history theory is contesting the democratic end-of-history one that Francis Fukuyama proclaimed when the cold war ended a quarter-century ago.

Trump’s election has launched an unsettling new normal for transatlantic relations, the West, and democracy.

Elizabeth Pond is a former European Bureau Chief for The Christian Science Monitor.