Why even some US allies are hedging their bets on Ukraine

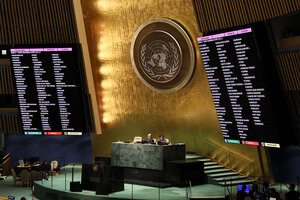

With the names of countries displayed on screen, voting starts in a special session of the United Nations General Assembly on Russia's invasion of Ukraine, at U.N. headquarters in New York, March 24, 2022. Nearly 50 states abstained or did not vote to condemn the invasion.

Brendan McDermid/Reuters

London

It is a compelling snapshot of the diplomatic jolt caused by Vladimir Putin’s attack on Ukraine: the remarkable shoulder-to-shoulder unity among the United States and its European allies in opposition to the invasion.

But like all snapshots, it doesn’t tell the whole story.

It’s like a close-up that misses key details that would be captured by a wide-angle lens: in this case, the dozens of countries across Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and Latin America that have been hedging their bets on the invasion and steering clear of unequivocal condemnation.

Why We Wrote This

The number of nations refusing to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine highlights a reluctance to take sides between the U.S. and a Russia-China axis. The “democracy vs. autocracy” battle may not be so straightforward.

In a United Nations General Assembly vote this month, only four of 193 member states sided with Russia in voting “no” on a call for an end to the aggression: Belarus, Syria, Eritrea, and North Korea.

Nearly 50 states, though, most of them in the developing world, either abstained or stayed away altogether.

And a number of other countries – including Israel and the Gulf oil states, Brazil, and NATO member Turkey – clearly voted yes only reluctantly.

The Gulf States promptly spurned U.S. President Joe Biden’s call for them to pump more oil and help Western Europe wean itself from Russian energy supplies. Israel ruled out any military help for Ukraine and, like Turkey, sought to position itself as a potential mediator between Kyiv and Moscow. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro pointedly declined to criticize Mr. Putin even after his country’s “yes” at the U.N., proclaiming neutrality on the invasion.

How exactly all this will affect the shape of world politics when the war is over may partly depend on how it ends. But the number and variety, both regional and political, of the “don’t knows” suggest a far more complex arrangement than the straightforward battle between democracy and autocracy that President Biden wants to wage.

It also poses a challenge for Washington and its allies: how to engage, reach out, reassure, and, where possible, reinforce ties with these countries – especially since they include key regional powers like India, South Africa, and Brazil.

Why the hesitancy to condemn Mr. Putin’s war?

There’s no single explanation, although a disproportionate number of the countries holding back are indeed undemocratic.

In some cases, the bet-hedging is down to Cold War-era ties with the Soviet Union, or current military and economic ties with President Putin’s Russia. In others, it’s a legacy of unresolved issues dating from Western colonial times or, in South America, historic resentment of U.S. policy. Other nations, such as Brazil and Saudi Arabia, are engaged in ongoing quarrels with Washington.

Yet more broadly, most of these countries seem to be looking toward a post-Ukraine-war world in which they figure they may be best off steering some kind of middle course between the U.S. with its democratic allies on the one hand, and Russia (and above all, China) on the other.

Even if Mr. Putin does emerge weakened from the war, both he and Chinese leader Xi Jinping have spent recent years building economic, political, and security ties with the developing world.

American outreach to the Ukraine holdouts will probably come to the fore only once the fighting in Ukraine is over.

India is a prime example. Though ruled by an increasingly Hindu-nationalist government, it remains the world’s most populous democracy. The Biden administration had been making efforts to strengthen U.S.-Indian relations before the Ukraine invasion.

Officials in Washington will be aware of Delhi’s desire not to burn diplomatic bridges with Moscow. Russia sells India both oil and half its weapons, and Moscow is seen as something of an insurance policy against further flare-ups on India’s border with China. But the U.S. will still hope to strengthen ties over the longer term.

South Africa may be viewed in similar terms: In its case, reluctance to denounce the invasion is due partly to the fact that veterans of Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress still remember, and value, Soviet support during apartheid.

Brazil could prove more complicated: The Biden administration has so far largely cold-shouldered President Bolsonaro, seeing him as a populist soulmate of former President Donald Trump.

The Middle East, too, could present a thorny challenge: The Gulf countries’ hesitancy about lining up behind the U.S. on Ukraine, and Israel’s too, reflects their growing concern over Washington’s retreat from their region given its “tilt” toward Asia and its competition with China.

With Washington now having to add new European military, economic, and diplomatic demands to its China focus, it is hard to see how it might seriously re-engage in the Middle East.

Overall, the geopolitical scenario most likely to emerge amid what’s being seen as a “new Cold War” may turn out to involve a throwback to the original Cold War: the 120-strong Non-Aligned Movement of nations that were not formally aligned with either of the then-dominant superpowers.

One of its founding prime ministers: Jawaharlal Nehru of India.