Why the US didn't intervene in the Rwandan genocide

After a disastrous peacekeeping mission in Somalia, the US vowed to stay away from conflicts it didn't understand.

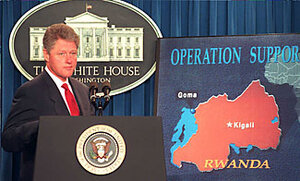

In this 1998 file photo, President Bill Clinton addressed reporters in the White House Briefing Room in July about the humanitarian situation in Rwanda. Four years after the Rwandan genocide, Mr. Clinton asked Congress to approve $320 million in emergency funds to supply food and water to hundreds of thousands of refugees in Rwanda.

AFP/NEWSCOM/FILE

Johannesburg, South Africa

The Clinton administration and Congress watched the unfolding events in Rwanda in April 1994 in a kind of stupefied horror.

The US had just pulled American troops out of a disastrous peacekeeping mission in Somalia – later made famous in the book "Black Hawk Down" – the year before. It had vowed never to return to a conflict it couldn't understand, between clans and tribes it didn't know, in a country where the US had no national interests.

From embassies and hotels in Kigali, diplomats and humanitarian workers gave daily tolls of the dead, mainly Tutsis but also moderate Hutus who had called for tribal peace. The information came in real time, and many experts say that the US and the Western world in general failed to respond.

'We knew before, during, and after'

"During World War II, much of the full horror of the Holocaust was known after the fact. But in Rwanda, we knew before, during, and after," says Ted Dagne, a researcher at the Congressional Research Service in Washington, who has traveled to Rwanda on fact-finding missions. "We knew, but we didn't want to respond."

In an official letter written as late as June 19, 1994, the then-UN-Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali showed exasperation at the numbers of peacekeepers that member nations were willing to provide.

"It is evident that, with the failure of member states to promptly provide the resources necessary for the implementation of its expanded mandate, UNAMIR (the United Nations Assistance Mission in Rwanda) may not be in a position, for about three months, to fully undertake the tasks entrusted to it," Mr. Boutros-Ghali wrote. Within a month of the writing of this letter, the genocide ended, as Paul Kagame's Rwandan Patriotic Front took full effective control of Rwanda.

US support for a rapid-action force

Mr. Dagne, a Congressional aide at the time, says that if the Clinton administration had called for a rapid-action force to stop the killings in Rwanda, Congress would have supported him. Letters from bipartisan panels of Congress back this up.

"We are writing to express our strong support for an active United States role in helping to resolve the crisis in Rwanda," wrote Rep. Bob Torricelli (D) of New Jersey, in a letter of April 20, 1994, signed by Republicans and Democrats alike. "Given the fact that approximately 20,000 people have died thus far in the tragic conflict, it is important that the United States endeavor to end the bloodshed and to bring the parties to the negotiating table."

But time and again in that spring and summer, President Clinton replied with more pleas for the government and the rebels to stop the violence themselves, and suggested that the underarmed, overstretched UN peacekeeping mission on the ground was the right group to lead the way.

"On April 22 ... the White House issued a strong public statement calling for the Rwandan Army and the Rwandan Patriotic Front to do everything in their power to end the violence immediately," President Clinton wrote on May 25, 1994, to Rep. Harry Johnston (D) of Florida. "This followed an earlier statement by me calling for a cease-fire and the cessation of the killings."

With Congress looking toward the president, and the White House looking toward the UN, nothing was done, and the genocide ran its course.

"At the end of an administration, they write a report, and Rwanda was at the top of the failures list for the Clinton administration, so this is something that they acknowledge themselves," says Dagne.

If there is a lesson learned from Rwanda, Dagne says, it is that the international community needs to avoid giving the impression that it is willing or capable of rescuing civilians in a conflict. "It's important to build the capacity of people to do the job themselves [of protecting themselves]," Dagne says. "We must not give the expectation that people will be saved."