Aid groups return to Darfur – with new names

The decision by Mercy Corps, Care, and others to go back to Sudan's troubled region after being kicked out in March opens fresh debate over how to deliver aid to people living under oppressive regimes.

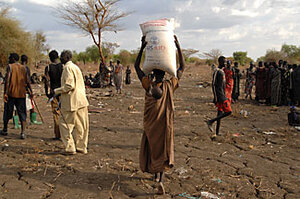

An internally displaced woman of the Murle tribe carries her ration of food from the World Food Program at a distribution point in Pibor, Sudan, on March 21. Sudan disputed a statement made by UN humanitarian chief John Holmes that it would allow expelled aid groups back into Darfur.

Tim McKulka/UNMIS/ AFP/NEWSCOM/FILE

Nairobi, Kenya

First, they were returning. In a statement last week, the United Nations chief humanitarian official said four aid agencies expelled from Darfur in March for "spying" had been given permission to come back to the wartorn region of Sudan, where more than 4 million people depend on help.

Then they were not.

Over the weekend, the Sudanese government said that it would not allow to return any of the 13 international groups kicked out as part of Khartoum's retaliation against the International Criminal Court's decision to issue a warrant for the arrest of President Omar al-Bashir.

Instead, the groups would have to register as new agencies in order to operate in Darfur. Critics say that is a cynical ploy by Khartoum to use the aid groups to help limit Darfur death tolls, while at the same time tightening the already firm limits on their freedom of speech and action.

Both Mercy Corps and Care have played along by releasing statements that they were not returning. Rather, Mercy Corps Scotland and Care Switzerland applied to work in the country.

The decision to return exposes rifts within the agencies and is opening fresh debate on how best to deliver aid to people living under oppressive regimes.

"This is exactly what we were worried about – that NGOs will now have to bend over backward to keep the government happy, putting out press releases like this that make no mention of the humanitarian emergency or the fact that they were expelled in the first place," says one aid worker with experience of dealing with Khartoum officials. "It's as if there are no red lines beyond which we won't be pushed."

The cost of being expelled

The British aid agency Oxfam estimates that expulsion cost $5 million in severance pay to national staff, confiscated cars, computers, and other equipment.

Members of staff had personal items such as iPods and laptops taken.

Many complained of heavy-handed treatment. Some were subjected to intimidating questioning by state security officers.

Others were detained in Khartoum and denied exit visas until their organizations forked over six months' pay to Sudanese staff who had lost their jobs.

Since then, aid officials have been campaigning for their return.

Heavy US lobbying

Sen. John Kerry (D) of Massachusetts and Scott Gration, President Obama's special envoy to Sudan, both lobbied the Sudanese government on the issue of aid groups' expulsions during visits to Khartoum.

Both left with assurances that expelled agencies could return as long as they adopted new names and logos.

As a result, Care Switzerland, Mercy Corps Scotland, and Padco, an international development consulting firm, have all begun the registration process. Save The Children Sweden is already operating in Darfur, after Save The Children US was expelled.

A bad precedent?

Aid workers will not speak openly about the decision, given the sensitivity of the subject. But some have privately expressed concern about the precedent it sets.

"It seems there is a big divide between [headquarters], which sees Darfur as a high-profile emergency and the sort of place it is important to work in, and people who worked there and suffered intimidation and bullying," says an aid worker now based in Nairobi, Kenya. "Khartoum now thinks it can do whatever it wants and get away with it. Who's to say we wouldn't spend millions of dollars building up our programs, only to be kicked out again in a few months?"

Saving lives

The organizations returning, however, say the only factor that matters is their ability to deliver assistance to people in need.

Ross Hornsey, spokesman for Mercy Corps Scotland, said: "Of course we don't have guarantees. We are happy to get our registration through, because there's a humanitarian imperative to get aid through."

He added that aid agencies often face bureaucratic and logistical hurdles given the nature of humanitarian emergencies, which often play out against amid war or civil unrest.

More than 200,000 people have died during six years of fighting in Sudan's remote western region.

Almost 3 million people have been forced into aid camps to escape clashes.

Aid desperately needed

More than 1 million of those were receiving food from expelled aid groups. Another million relied on organizations like Care and Oxfam for drinking water.

Medical teams from Doctors Without Borders were tackling two meningitis outbreaks when they were expelled.

For now, aid officials believe many short-term needs are being met by aid groups and United Nations agencies that remained in Darfur. But they warn that the long-term impact could be devastating, particularly with the rainy season starting this month.

Sudan's new twist on divide and rule

Fouad Hikmat, Darfur analyst with the International Crisis Group, says Khartoum was up to its old tricks, using tactics of divide and rule – this time directed at aid agencies, rather than tribes or rebel groups.

"I would have thought [the aid groups] should have stuck together, insisted they had done nothing wrong, and established clear criteria for their return – guarantees on access, security, visas, an end to smears in the media. With that established, then they could think about returning," he says. "Instead, Khartoum has done a rather clever job of giving the US envoy what he wanted, but without any guarantees [that] conditions for the NGOs are going to be any better."