At last, a court to try Somali pirates

Most navies catch and release Somali pirates. But Kenya's new pirate court, funded by the UN, aims to bring legal clarity to a complex international crime.

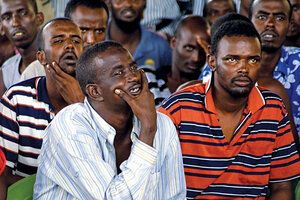

Unidentified suspected Somali pirates at the Shimo la Tewa Prison near Mombasa, Kenya, listen as they are addressed by the head of the European Union delegation to Kenya. The suspects await trial in a new court paid for by a coalition of nations through the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

AP

Nairobi, Kenya

On a busy road within sight of the white sands of Kenya's Indian Ocean beaches, a stone's throw from luxury tourist hotels, a tall, black, barred gate is guarded by a man with an automatic rifle.

Beyond it, up a short driveway, stands the imposing breeze-block building that is now the focus of international efforts to prosecute Somalia's pirates. It is Shimo la Tewa maximum-security prison, 10 miles north of the coastal city of Mombasa.

Last week, the first hearings were held in a courtroom designed to ease the immense pressure on a country leading the way in bringing pirates to justice.

The court was paid for with money from the United States, the European Union, Canada, Australia, and others, channeled through the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). "This, we hope, is going to go a long way to improving the efficiency of the trials, in a secure, modern environment," says Alan Cole, coordinator of a counterpiracy program at the UNODC office in Nairobi.

There had been concerns over busing suspected pirates daily to and from the main courtroom in Mombasa, which does not have a secure dock and which is swamped with nonpiracy cases. There, witnesses, lawyers, and the public milled around, raising further worries about security. With the court now on the grounds of the prison holding the suspects, concerns have been eased, Mr. Cole says.

Kenya is holding the highest number of piracy suspects in the region, with 105 on trial and 18 already convicted, with sentences ranging from seven to 20 years. Other Somali pirate suspects are being tried or held in the US, Germany, Spain, and France. In the Netherlands last month, five Somalis were sentenced to five years each in the first convictions of Horn of Africa pirates in Europe.

Puntland (the breakaway enclave north of Somalia), the Seychelles, and the Maldives hold others. But how Mombasa became the de facto headquarters of modern world piracy trials is unclear and open to legal question, critics say.

As attacks by the seaborne buccaneers soared in 2009, Kenya signed a memorandum of understanding with the US and Britain, and undertook an informal agreement with the EU, to prosecute pirates arrested in the waters off its anarchic neighbor. Before this, the legal framework was opaque, drawing partly on jurisprudence from the Barbary Wars off North Africa 200 years ago.

Most navies that capture Somalis engaged in piracy in the Indian Ocean typically release them after confiscating their weapons. The catch-and-release policy means most suspected pirates are put back in their boats, and are free to return to Somalia and go back to stealing ships and ransoming them.

One reason for the catch-and-release policy is that it's not clear which country should prosecute these cases.

"The situation is further complicated by the fact of multiple jurisdictional aspects of international shipping," Edward White, an expert in admiralty law in Jacksonville, Fla., wrote in a recent analysis.

Vessels often are flagged to countries with cheap licensing, like Liberia. The ship might be owned by a firm in a second country, chartered by one in a third, and crewed by sailors from still elsewhere.

But most Western nations have been wary of agreeing to capture pirate suspects, many of whom were expected to claim asylum in the countries where a trial is held.

The Indian Ocean archipelago of Mauritius, was approached first, eventually refused to host the pirate court. Kenya stepped up last year. Its penal code prohibits piracy, it borders Somalia, and its judicial system was seen as one other countries could work with.

But the process is slow. Witness depositions are hard to gather. There were worries over what to do with pirates once they complete their sentence, or are acquitted. Kenya complained it could not pay to return dozens of Somalis to their homeland, and was worried that they would stay in Kenya. (Canada has offered funds to the UNODC for repatriations, Cole says.)

But as the cases built up in a judicial system clogged by more than 1 million trials dating to 1984, according to a recent report, authorities became frustrated. The justice minister snapped earlier this year that Kenya would stop accepting pirate suspects unless other countries helped. It is a strategy that appears to have paid off.

First, the courtroom at Shimo la Tewa was built with $5 million of international donations. The Seychelles agreed that it, too, would prosecute pirates. The UNODC is refurbishing the main prison in Victoria. Tanzania will soon begin talks over taking suspects.

"It's important that we get more help," says Donald Muyundo, a defense lawyer representing pirate suspects. "Building a new court is not enough. What about training more magistrates, employing more translators, helping the defense build its capacity in the way that prosecutors have been helped. They have the backing of the international community. For the defense, it's just me."

RELATED STORIES: