A 'novel' idea for spreading literature in Africa: The cellphone

Publishers across the continent are increasingly targeting readers with mobile phone apps and other technologies that are far cheaper than either e-readers or traditional books.

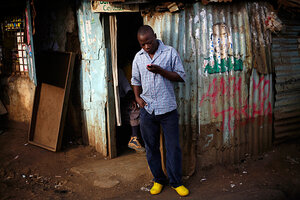

A man wearing yellow shoes checks his phone in Kibera, Africa's largest slum, in Nairobi, Kenya, in March. Cellphones are 'a huge component of how consumption is happening here,' Angela Wachuka, executive director of Kenya’s Kwani Trust says.

Jerome Delay/AP

New technology and new thinking are helping African literature leapfrog the high costs of traditional publishing and reach new readers across the continent.

As e-readers boom in popularity in the West, African publishers are stretching their reach with the help of a device millions already have in their pockets: their cellphones.

"You can give people instant access to work now," says Angela Wachuka, executive director of Kenya’s Kwani Trust, which publishes the popular Kwani? literary journal. "Before, you had to rely on delivery or people coming to find you."

Mobile internet now accounts for well over half of all web traffic in some African countries, and it is expected to grow 25-fold on the continent in the next four years, according to the Groupe Speciale Mobile Association, an industry organization.

Cellphones are "a huge component of how consumption is happening here," Ms. Wachuka says, noting that she's seen Kenyans devour hundreds of pages of text on their tiny screens, plowing through tell-all memoirs and other accounts of the country's recent political turmoil.

For now anyway, much of that literature is pirated, but Kwani is taking the approach that if the e-literate get a taste for free, at least some will pay for more.

There's an app for that

To that end, the group has been working with experts from Nairobi’s pool of mobile phone innovators to develop its own literature app, which will run on both smart phones and the "feature phones" ubiquitous around the continent, which offer Internet connectivity but are cheaper and less sophisticated than their smart phone cousins.

Wachuka envisions making 600- to 2,000-word excerpts from Kwani? literary journal available via the app, which she expects to be tested in the next few months and launched in November. The app is expected to be rich in supplementary features as well, she says, including podcasts, videos, and interactive content like chats with writers and text-message poetry contests.

Going digital has meant "a complete revamp of how we produce content," Wachuka says. "We’re basically creating an entirely new product. It’s an extension of what we do already, but it’s a reshaping of things and spaces.’’

Last year, Kwani for the first time worked with 3Bute (pronounced "tribute") a site where users can access graphic novel versions of fiction and journalism. But 3Bute is not a read-only experiences. Users can add comments that pop up on the screen, becoming part of the story.

Dan Raymond-Barker, books marketing manager at UK-based New Internationalist, a non-profit publisher, cites 3Bute and Kwani as examples of the innovative, collaborative thinking Africans are bringing to e-publishing.

"It’s not necessarily about the commercial approach – selling books. It’s about people sharing ideas," he said. "You capture someone’s imagination. You capture their interest. By doing that, you have opened the opportunity to sell them something."

A new literary conversation

New Internationalist works with Kwani and other publishers in Africa to distribute anthologies – including in e-book form – of winners of the Caine Prize, which recognizes outstanding African short story writers.

Increasingly in recent years, Mr. Raymond-Barker says, bloggers in Africa and elsewhere have fueled discussion of Caine Prize shortlisted stories, which New Internationalist makes available on its web site before the winner is announced.

"That’s another great thing that’s happening, the way people can talk about anything, including literature" on the Internet, Raymond-Barker says. "The consumers are becoming the reviewers, the critics."

Last year, 3Bute created mashups of the Caine Prize short list, says Caine Prize administrator and literary scholar Lizzy Attree. Her organization also works with publishers to produce e-anthologies, the first in 2009.

"In Africa, where distribution is so hard, e-publishing is the way forward," Ms. Attree says. It is "the key to getting younger people involved."

She acknowledged, though, that much of the potential has yet to be realized. She still hears complaints from readers in Africa that bandwidth limitations can make downloading an e-book slow and uncertain.

Reaching new readers

Attree has put Caine Prize winners in touch with Worldreader, a Western, donor-funded non-profit that distributes pre-loaded e-readers to schools across Africa and has recently developed its own mobile reading app, which it says is now on 5 million phones, most of them in Asia and Africa.

She encourages them to allow the organization to use their work for free. Short stories, she says, may be particularly attractive for someone reading on a mobile phone.

"We have a great faith in the short story as such a vehicle for our time," she says.

Like Kwani’s Wachuka, Attree believes that readers who start with free stories might go on to buy books. They also might go on to be writers who will one day submit short stories to Caine Prize judges, Attree says.

Sudanese novelist Leila Aboulela is a Caine Prize awardee who allowed Worldreader to include her winning story, "The Museum," in its library.

"It’s a very good way of reaching points of the world where it’s difficult for books to reach," Ms. Aboulela says.

From her home in Scotland, she says she can easily imagine her short story being read on mobile phones in Africa.

Unlike in the West, she says, many African readers grew up with phones as their primary reading device, rather than books or computers.

"People there are much more comfortable with technology than even we are here in the West," she says.