Suppressed under apartheid, Namibia’s music survives in ‘Stolen Moments’

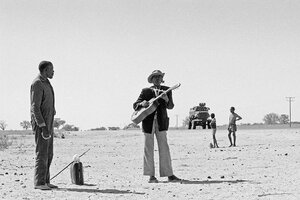

A musician plays the guitar in this archive image from Namibia. The project “Stolen Moments” is cataloging thousands of Namibian pop songs from the apartheid era.

John Liebenberg/Courtesy of Stolen Moments

The music was like nothing Aino Moongo had ever heard before. A whistle floated above a skittering guitar melody, and then a voice broke in, low and mournful.

When her friend, the German filmmaker Thorsten Schütte, shared the recording of Namibian singer Ben Molatzi with her in 2010, Ms. Moongo, who had worked in the entertainment industry for years, was stunned.

Why had she never heard of this musician, she wondered? What was his story?

Why We Wrote This

Why are artists so often targeted by regimes? Perhaps, under apartheid, it was black singers’ audacity to assert that their lives and dreams mattered – and stretched beyond segregation’s rigid boundaries.

Together, the pair, along with Namibian musician Baby Doeseb, began to investigate, touching off a project that would eventually sprawl across the past decade and two continents: to collect and revive the vast catalogue of Namibian pop music censored and suppressed under apartheid South African rule.

Imagine you were used to “the blaring church and propaganda songs that were sold to you as your country’s musical legacy,” Ms. Moongo wrote ahead of an exhibition in London last year based on the project, which is called “Stolen Moments.” “Until all at once, a magnitude of unknown sounds, melodies and songs appear. This sound, that roots your culture to the musical influences of jazz, blues and pop from around the world, is unique, yet familiar. It revives memories of bygone days, recites the history of your homeland and enables you for the first time to experience the emotions, joys and pains of your ancestors.”

Until its independence in 1990, Namibia was a colony of South Africa, subject to its humiliating system of segregation. Apartheid dictated where black South Africans and Namibians could live and who they could love, the kinds of work they could do and the kind of education they could receive.

In this system, the very act of pop music itself was a rebellion, says Ms. Moongo, because it was a reminder that black people still lived audaciously, stretching beyond apartheid’s ambitions. As the lyrics of the 9,000 songs in the “Stolen Moments” catalogue attest, they loved and dreamed and searched for identity, they celebrated life’s milestones and pined for the pretty girl down the road. And most of all, they snatched joy from the jaws of a system enforced by brutality.

“What’s remarkable to me about this music is that it takes Western pop music and mixes it with African musical traditions and experiences, so in a sense it’s taking something that was imposed on you and transforming it to be your own,” says Henning Melber, a Namibian-German political scientist and author of the recent Op-Ed, “Pop culture: restoring Namibia’s forgotten resistance music.”

“To me that’s an extremely subversive act of resistance.”

The apartheid government seemed to agree. For decades before Namibian independence, pop musicians and their fans were hassled, arrested, and prevented from releasing records. What little music was recorded, meanwhile, was played on radio stations segregated by language, ensuring that even the most popular bands couldn’t profit widely.

“When we started searching for these musicians and doing interviews, we often hit a wall. So many people didn’t want to go back into their memories of this painful era,” Ms. Moongo says.

That’s true, she says, not just for musicians but for the country as a whole. Ms. Moongo, who grew up as a refugee in Sweden, says she eventually stopped asking her parents about their early lives in Namibia because she could see the immense pain those memories churned up. “Many young Namibians are in the same situation as me, and it’s hard to build a country like that, that doesn’t remember its own past,” she says.

But slowly, she says, the “Stolen Moments” archive is helping to unfurl those memories, and remind Namibians of their own rich musical heritage.

“That shouldn’t be just something that’s stored gathering dust in the belly of the state broadcaster,” she says. “It needs to be heard.”