The national archives built from a crumpled napkin

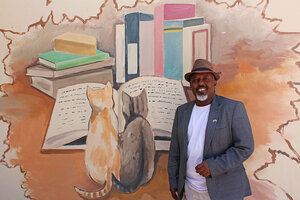

Hargeisa Cultural Center founder Jama Musse Jama, a mathematician and publisher, poses in front of one of the many murals scattered throughout the complex.

Ryan Lenora Brown/The Christian Science Monitor

Hargeisa, Somaliland

How do you build a national archive for a country that doesn’t exist?

The same way you build anything here. From the ground up. In this case, quite literally.

It was 1991, and in the bombed-out ruins of Somaliland’s newly proclaimed capital city, a woman selling camel milk tea and laxoox, spongy Somali pancakes, handed a customer a piece of paper off the ground so that he could wipe the dirt off his hands.

Why We Wrote This

This book lover from Somaliland launched a library to bring the world back home. But his carefully curated archives send another message, too: Our own history, our culture – our humanity – matter just as much.

But as Jama Musse Jama prepared to crinkle the paper in his hands, his eyes snagged on the text. These were the trial records from a famous court case a decade earlier that had sent hundreds of student activists to prison.

Mr. Jama was on his way to Italy, where he was to begin work as a mathematics professor. But in the meantime, he asked the tea seller if he could take the rest of her papers, which she had gathered off the road near her stall. And then he wandered the rest of the gutted-out city center, picking up whatever he could find.

At the time, Somaliland was mostly trying to forget. For three years, it had been bombed into submission in a brutal civil war waged by Somalia’s government in Mogadishu. Up to 90% of its capital, Hargeisa, was destroyed. It had recently declared its independence, trying to build something new from the rubble.

But one day, Mr. Jama thought, Somaliland might want to remember.

Three decades later, the papers he gathered in 1991 have become the foundation of the library and informal national archive he is building here. Like Somaliland itself, the project is a radically DIY institution, built from the bottom up with little outside help. And also like the self-declared republic, which is not recognized by a single other nation, its very existence is an act of defiance.

“This country is poor. Most of its budget must go to the basic needs of its citizens ,” says Mr. Jama in the melodic, Italian-inflected English he perfected during his years in Pisa. “But when you remove arts and culture from the equation of a society, you remove the thing that makes humans humane. I wanted to make sure that never happened here.”

Bringing readers the world

“Here,” of course, is a place that technically does not exist. Not on a world map. Not in the United Nations General Assembly. Not on the roster of FIFA member states, or the Olympics’ Parade of Nations.

As far as the world is concerned, Somaliland is just a province of Somalia that has, in the words of the CIA World Factbook, “secessionist aspirations.” But on the ground, its independence hardly feels aspirational. It has its own government and its own borders. There is a Somaliland police force, a Somaliland army, a Somaliland shilling. It holds its own elections and collects its own taxes.

But the nation’s lack of recognition has left it deeply isolated. Most Somalilanders cannot travel, either because their passports aren’t recognized or because they simply don’t have the money.

A decade and a half ago, that isolation led Mr. Jama to an idea many considered outlandish.

“You want to give people access to the world,” he remembers thinking. “And since most people here cannot travel, the world must come to them, and what better way than through books.”

Not everyone agreed.

“People said, this isn’t the right place, this isn’t the right time,” he says. But he tuned out those voices, and in 2008, he organized the first Hargeisa International Book Fair.

That year, 200 people came to the event. By the 2010s, that number had soared to nearly 10,000.

Not just any books

But Mr. Jama worried about what would happen to that enthusiasm the other 360 days of the year. There were few bookshops in Somaliland, and even fewer libraries. What was there left much to be desired. He remembers browsing a library in the coastal city of Berbera that had been stocked with books from overseas donors. On the shelves he found five dozen pristine, unread copies of a text called “Coping With Alcoholism” – awaiting readers in a place where alcohol is illegal and “you can probably count on one hand the number of people with a drinking problem,” he says.

So when he founded the Hargeisa Cultural Center in 2014 and began building its library, he had one strict rule: No donated books, unless the title was one he and his librarians had specifically requested.

“We didn’t want castoffs,” he says.

For librarian Moustafa Ali Ahmad, that rule is important. Africans, he says, shouldn’t see their libraries as charity projects where Westerners’ well-thumbed beach reads and self-help books go to retire. Instead, he says, he tries to build the kind of library he wishes he had access to as a child – full of African fiction and thick reference books.

“I believe deeply in the idea of traveling through books,” he says.

Today, the library builds its collection through a wish list compiled by center librarians and patrons, which prospective donors can buy from. When he travels back and forth from Europe, Mr. Jama lugs home a suitcase full of new books for the library.

But perhaps the most important element of his collection, and the centerpiece of the archive he began compiling three decades ago, is a collection of 14,000 cassette tapes.

Their contents capture the deep orality of Somaliland society. Some contain underground pop music banned under Somalia’s Siad Barre regime of the 1970s and ’80s. Others are poems, radio plays, or recordings of news broadcasts. And many are simply oral “notes,” recorded and mailed back and forth between families in Somaliland and their relatives in the diaspora.

“This is the heart of our society,” Mr. Jama says. “And this is the heart of our archive.”