Doha agreement could actually worsen chances for peace in Darfur

Guest blogger Laura Jones from the Enough Project writes that the Doha peace process in Darfur is more a fig leaf for the Sudanese government than genuine progress.

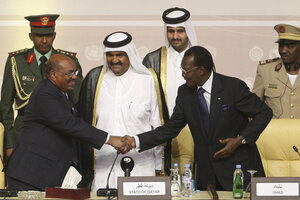

Sudan's President Omar Hassan al-Bashir (L) shakes hands with his Chadian counterpart Idriss Deby as Qatar's Emir Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani (2nd L) looks on after the official signing of a peace accord between Sudan and Darfur rebel group Liberation and Justice Movement (LJM) in Doha on July 14.

Reuters

Late last week, the Sudanese government and the Liberty and Justice Movement, or LJM, agreed to adopt the Doha Document for Peace in Darfur, as well as a separate protocol on LJM’s political participation and the integration of its limited forces into the national army. While the signing of these documents could in many ways be considered progress, there is little hope that they will lead to any sort of comprehensive and sustainable peace for Darfur.

There have been numerous indications that the results of Doha will, in fact, be little more than a blip on the radar screen, particularly for those still in Darfur. The first and most frequently discussed flaw is the lack of inclusion of key rebel groups in the agreement, including the Justice and Equality Movement, or JEM, and the factions of the Sudan Liberation Army, SLA-Minni Minnawi and SLA-Abdel Wahid. These groups are still engaged in military operations on the ground while the Sudanese Armed Forces continue to aerial bomb their suspected locations. Further, unlike these other groups, LJM was in many ways the creation of international mediators involved in the Doha process keen on unifying the many rebel factions in Darfur into a single entity that would negotiate with the government on behalf of the people of Darfur. The real result was a rebel group with limited political or military influence on the ground and little support from Darfuris. The All Darfur Stakeholder Conference which was meant to gain popular support for the LJM-negotiated agreement was itself defective in that participation was in many respects controlled and those present at the conference never actually reviewed the document. The ability of LJM to actually assist in the attainment of peace in the region is therefore highly in doubt.

The international community’s enthusiasm for the outcome of the two-year process was well-reflected in the attendance at the signing ceremony on July 14. While a number of African dignitaries, including the presidents of Chad, Eritrea, and Sudan itself were present at the event, high-ranking western diplomats were conspicuously absent. The implication, of course, is that none of the western countries involved in the negotiations felt this event significant enough to attend – a poor indication of how successful they feel this agreement is likely to be.

Unfortunately, the outcome of the Doha process may be worse than just ineffectual; there is a very real possibility that it will negatively impact future negotiations and processes. After the signing of the LJM-government deal, the government’s representative told JEM that any further negotiations would be limited to the status of combatants and participation in government, despite the fact that JEM had earlier provided significant changes to the draft text of the main peace document. JEM was also informed that it had three months to make the decision to sign on to the LJM agreement. True to form, the government is thus removing the possibility of meaningful negotiations with a group whose buy-in is necessary for ending conflict in Darfur, while claiming that it is genuinely seeking peace.

The outcome documents from Doha also allow the government to push for a domesticated process, which it has been anxious to launch since the introduction of its New Strategy for Darfur late last year. By claiming that it legitimately engaged in the Doha process and signed a peace document, the government will likely feel it has legitimate grounds to push for the ‘next phase,’ which is engagement in Darfur. This approach has gotten some degree of support from the likes of Ibrahim Gambari, the African Union-United Nations Joint Special Representative for Darfur and the new interim joint mediator, who is pushing a similar move known at the Darfur Political Process, or DPP. Yet moving the peace process inside Darfur only facilitates government manipulation and avoids any sort of international oversight or criticism. The opening for a new internal process that the signing provides could therefore work against the prospects for long-term peace and stability.

While any document that speaks of a move toward peace should be recognized as a positive development, it is important that the international community recognizes the potential for the situation to deteriorate as a result. Moving forward, it is essential that that the international community isn’t hoodwinked yet again. If we’ve learned anything from our engagement with the Sudanese government, it’s that "progress" in Sudan generally comes at a price that is paid by its people.

– Laura Jones blogs for the Enough Project at Enough Said.