Colombia's 'neo-paramilitaries' on the rise

'Successor groups' of right-wing paramilitaries are growing fast, causing a steep rise in violence in many areas, according to a new report from Human Rights Watch.

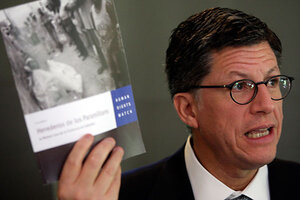

Director of Human Rights Watch's Americas division José Miguel Vivanco holds up the organization's report on Colombia during a news conference in Bogota Wednesday. US Congress will likely pass a free trade deal with Colombia if the Andean country confronts rising violence by former paramilitary leaders who have formed new crime gangs, Washington-based Human Rights Watch said.

John Vizcaino / Reuters

Bogotá, Colombia

New criminal organizations born from defunct paramilitary groups pose an increasing threat to human rights and security in Colombia and often function with complacency from local authorities, Human Rights Watch warned in a report released Wednesday.

Human Rights Watch said that by the most conservative estimates, the “successor groups” of right-wing paramilitaries have at least 4,000 members. The organizations, mostly led by former mid-level leaders of the militias, regularly kill, commit massacres, and forcibly displace individuals and entire communities. And as the ranks have swelled, the groups have consolidated into six main organizations and are present in 24 of Colombia’s 32 provinces.

The groups are committing “egregious abuses and terrorizing the civilian population in ways all too reminiscent of the AUC,” the report said, referring to the federation of paramilitary groups called the Self-Defense Forces of Colombia.

The new independent groups are sometimes known as “neo-paramilitary” groups, but the government generally refers to them as BACRIM, short for criminal bands.

“Whatever you call these groups … their impact on human rights in Colombia today should not be minimized,” said José Miguel Vivanco, Americas director at Human Rights Watch. “Like the paramilitaries, these successor groups are committing horrific atrocities, and they need to be stopped.”

(You can read the Human Rights Watch report here.)

Locals raise alarm

Local human rights groups and conflict analysts have also raised the alarm over the “heirs” to the paramilitary militias that demobilized under a deal with the government between 2003 and 2006. The Nuevo Arco Iris Corp., a think tank in Bogotá that tracks the evolution of Colombia’s four-decade-old conflict, said in its yearly report that violent activity by these successor groups in 2009 topped that of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the country’s main leftist rebel group.

In some areas, the groups’ operations have resulted in a dramatic increase in violence. In Medellín, for example, the homicide rate has nearly doubled in the past year, That has led President Álvaro Uribe to propose a controversial plan to pay students the equivalent of $500 a month to act as informants on the new criminal bands that are fighting for control of the city.

Less ideological

Like the demobilized militias, the new groups are dedicated for the most part to managing drug production and trafficking routes, but they do not seem to have a central command or the political slant of their forebears.

“Whether they are political or not, the government has the responsibility to protect human rights,” said HRW's Maria McFarland, who authored the report.

And the Fundacion Ideas Para La Paz research group warned in a separate report last month that these groups could consolidate into a loose federation similar to the one that brought together the paramilitary militias. "It is probable that the phenomenon is moving toward [the groups] seeking recognition as political actors in the armed conflict even if these groups dedicate most of their efforts to drug trafficking and other illegal businesses,” the report said.

Mr. Vivanco said the Uribe administration has failed to treat the rise of the successor groups with sufficient urgency. “The government has taken some steps to confront them, but it has failed to make a sustained and meaningful effort to protect civilians, investigate these groups’ criminal networks, and go after their assets and accomplices.”

Human Rights Watch also expressed concern over the reported tolerance of the activities of successor groups by some local authorities, noting that both prosecutors and senior members of the police said that such acquiescence was a real obstacle to their work.

Nonetheless, police reported capturing 2,118 members of the successor groups last year and last week announced an offensive in 18 provinces against them. The government has offered up to $250,000 for information leading to the capture of the leaders.