El Salvador election: Is 'democratic revolution' fading?

As Salvadorans go to the polls to elect their next president, the leading FMLN remains torn between its guerrilla heritage and the need to play politics and win votes.

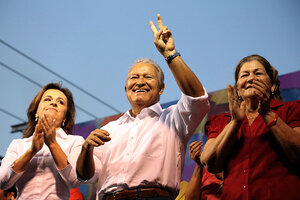

Current Vice President and presidential candidate of the ruling Farabundo Martí Liberation Front (FMLN) Salvador Sanchez Ceren, flashes a victory sign to supporters flanked by his wife, Margarita Villalta (r.), and first lady Vanda Pignato, at his closing campaign rally in Soyapango, El Salvador, Wednesday, Jan 29, 2014.

Luis Lopez/Salvador Sanchez Ceren presidential campaign press office/AP

SAN SALVADOR

Tomás Minero joined the Farabundo Martí Liberation Front (FMLN) as a teen in the 1980s, just as this country’s bloody civil war was getting underway.

For the next 11 years he fought for the Marxist guerrilla group: running offensives, escaping prison, and getting shot twice.

After the FMLN signed peace accords, disarmed, and became a leftist political party in 1992, Mr. Minero and many other former fighters followed. Minero is now mayor of Ciudad Delgado, a crowded, working-class municipality just northeast of El Salvador’s capital.

“It’s a thousand times harder to be a mayor than a guerrilla,” he says, sitting in his sparsely decorated office. “As a guerrilla you need only to fight, to plan, and to have a strong conscience. To be a mayor you’re not dreaming, but resolving.”

Minero’s dilemma is representative of today’s FMLN as a whole.

It took the FMLN replacing its hard-line former comandantes with Mauricio Funes, a popular television journalist without guerrilla ties, for it to win the presidency in 2009 after nearly two decades of conservative rule.

As Salvadorans go to the polls today to elect their next president, the FMLN remains torn between its guerrilla heritage and the need to play politics and win votes. And where it had formerly called out other parties’ shortcomings as the longtime opposition, it has since found itself accused of concealing its role in a controversial truce between gangs, and is taking heat for underhanded legal maneuvers and business dealings.

The FMLN is "more interested in conquering the hearts of the old oligarchy – because they’re now their business partners – than conquering the hearts of the poor,” says William Osmar Chamagua, a pastor and the director of Radio Mi Gente, a community station in San Salvador.

The presidential race is projected to be tight, with FMLN candidate and current Vice President Salvador Sánchez-Cerén slightly edging out conservative National Republican Alliance (ARENA) party candidate Norman Quijano in polls, with a third-party candidate, former President Antonio Saca, siphoning votes from the right. No candidate is expected to gain the necessary 50 percent of the vote in this first round, and the race is expected to go to a runoff next month.

'The' opposition

“The FMLN today is very different from the FMLN of the war,” Mr. Chamagua says, adding that changes are to be expected when former guerrillas go from the mountains to legislative seats and business meetings in fine hotels.

Following the peace accords, the FMLN gained steadily in influence and even seemed poised to win the presidency in 2004, until the party nominated hard-line former guerrilla commander Schafik Handal as its candidate. Mr. Handal died two years later, and his death, some say, paved the way for the alliance of the FMLN and now-outgoing President Funes.

Conservative politicians couldn’t scare voters by painting Funes as a communist, and Funes’s election “permitted [the FMLN] to work with sectors of society that would not [otherwise] work with” them, such as business leaders, says Minero, the mayor. The Funes administration has overseen some successful transportation and infrastructure projects, partly thanks to such relationships.

But during its five years in power, the FMLN has been quick to deflect criticisms and, some say, silence opposition. Protests broke out in June 2011 after Funes signed a law demanding all five judges in the country’s highest court reach unanimity to hand down a ruling. Many regarded the move as political — a way to chastise judges who’d taken on thorny corruption cases, and to keep a war-related amnesty law from being challenged.

Last September, United States Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) cautioned against extending some $277 million in US investment aid to El Salvador, saying it remained “a country of weak democratic institutions where the independence of the judiciary has been attacked,” among other sharp criticisms. Funes and Mr. Sánchez-Cerén responded defiantly, calling Mr. Leahy ill-informed.

In recent months Funes and the FMLN have come under fire for denying their role in a truce between the country’s two most violent street gangs. And an investigation by the online newspaper El Faro revealed that an $800 million energy conglomerate, Alba Petróleos, has ties to high-level members in the FMLN – something government officials won’t publicly address.

The FMLN has difficulties dealing with criticism, in part “because they have always thought of themselves as the opposition,” says Ellen Moodie, associate professor of anthropology and Latin American studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The party, which has shed its Marxist ideology and claims “democratic revolution” as its aim, has broken with traditional social movements, such as communal organizations of workers and farmers, says Dagoberto Gutiérrez, part of the FMLN’s high command during the war and now a vice rector at San Salvador’s Lutheran University.

Critics on the left, including Mr. Gutiérrez, say most of the social programs FMLN has instituted are little more than giveaways to the poor: free glasses of milk in schools, shoes for children, and school supplies.

Though the FMLN has instituted credits for small farmers and reduced school fees, most of its programs are “palliatives – not something that will break the cycles and generations of poverty,” says Jeannette Aguilar, director of the Institute of Public Opinion at the Central American University in San Salvador.

But they have generated goodwill, especially among voters in poor rural areas, Ms. Aguilar says, and this is helping Sánchez Cerén in the polls.

For an ex-guerilla leader like Gutiérrez, “The FMLN died when the war died.”

On a weekly radio show he hosts on Radio Mi Gente, Gutiérrez recently told listeners that not voting, leaving the ballot blank, or writing null are all valid options at the polls — and a way to show discontent with the nation’s politics.