Brazil could elect first black president – so why isn't anyone talking about it?

Marina Silva is Brazil's first presidential candidate to identify herself as black. It hasn't been treated as a landmark moment in this majority afro-descendant population, however, despite an ongoing struggle with racial inequality.

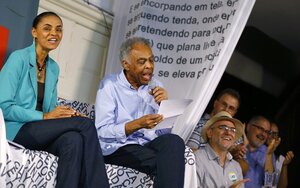

Brazilian singer Gilberto Gil sings a song he composed for presidential candidate Marina Silva of the Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB) during a meeting with artists and intellectuals at a campaign rally in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Ricardo Moraes

RIO DE JANEIRO

The official jingle for Marina Silva's presidential campaign discreetly refers to the candidate's skin color: “She’s going to come with her tan skin and popular appeal.... She’s going to be so different, and for that reason, so similar to all of us.”

The brief line – among diverse references to how she appeals to all Brazilians of all creeds – is symbolic. After her years in the public eye as a politician and activist, Brazilians know well the personal story of Ms. Silva: She hails from an impoverished family of 11 children in a remote corner of the Amazon, worked as a housemaid, and was illiterate until the age of 16. She’s a devout Pentecostal Christian and an outspoken environmentalist.

But in one of the most diverse nations in the world, few are talking about the fact that, if victorious, Ms. Silva would be Brazil’s first president who identifies as black. It’s put a spotlight on how race is – and isn’t – discussed here, and what that means for a nation that often describes itself as a “racial democracy” but still suffers from deep inequality and discrimination that fall along racial lines.

“If you look closely, people don’t speak about racial issues. It’s so complicated,” says Rodrigo Ledo, a press manager for the Brazilian Socialist Party, for which Silva became the presidential candidate after her running mate died in an August plane crash. “We have the aura of living in harmony, despite there being so much prejudice. It’s part of our education as Brazilians,” Mr. Ledo says.

'Racial democracy'?

Brazil is the second-largest country of afro-descendants in the world, behind Nigeria. Some estimates say Brazil accounted for 30 to 40 percent of the trans-Atlantic slave trade during its colonial period, a higher percentage than the United States. And according to the 2010 census, Brazil is now a “majority minority” nation, where more than half the population does not identify as white.

But the economic disparity of white and black Brazilians is still readily apparent here, where race and class are deeply intertwined. It’s routine for employers to speak about their workers needing to have “good appearance,” an oblique reference to not looking "low-class," or black. While Brazilians of all colors are increasingly going to college, the percentage of whites who go on to higher education in Brazil is still nearly double that of blacks and mixed-race Brazilians. In Brazil, already the country with the highest absolute number of annual homicides worldwide, two of every three homicide victims are black.

Unlike the United States, which hailed the election of its first black president as a milestone in the fight for a more equal and just society, many Brazilians don't see the context of Silva's campaign in the same light. For starters, the nations' histories are very different: Brazil never had overtly racist segregationist laws like the US, and many say that the attention paid to race relations in the US isn't relevant here.

It’s common to hear Brazil referred to as a “racial democracy,” a phrase put forth by 20th century anthropologist Gilberto Freyre. His views – as controversial as they are widely accepted – painted a picture of a less morally repugnant institution of slavery in Brazil than elsewhere. He praised racial mixing as enriching Brazilian culture.

“Here there is the myth of racial democracy, that we are all equal, so we don’t need to speak about racism and we don’t need to speak about race,” says Thaís Santos, a social science student at the University of São Paulo and member of the university’s black student association.

Ms. Santos says that if Silva emphasized her race in the campaign, she would be asked delicate questions on issues affecting black Brazilians, such as quotas for black students in public universities and the racial tensions sparked by heavy-handed police policies. That’s why for some, like Santos, Silva’s campaign feels like a missed opportunity. “Why does she speak about social inequality but not want to speak about blackness?” Santos asks.

It’s not that Silva ignores the topic: Occasionally on the campaign trail, she has referred to her desire to become “the first black woman elected president." But emphasizing her race, as Santos points out, could alienate her from more conservative sectors of Brazilian society. Those sectors see Silva as the most viable opponent to the dynastic Workers Party (PT), which could now win its fourth term in office. Silva is expected to face President Dilma Rousseff in a runoff after Sunday’s first round of voting.

Understanding diversity

Ana Paula Silva, an anthropologist who has written about race in Brazil, says that Brazilians traditionally identify by appearance, which leads to a variety of terms like “moreninho” (a little tan) or “mestiço” (mixed race). This is in contrast to the historic use of a so-called “one-drop” mantra in the United States, which largely defined someone as black if they had a black ancestor. That cultural practice, Ms. Silva says, is changing here as black Brazilian activists adopt an outlook that encourages Brazilians with African descent to identify more broadly as black.

Some say even if Silva is victorious this month, she won’t actually be the first black president – only the first to identify herself publicly as black. Nilo Peçanha, who served as president for just over a year between 1909 and 1910, is widely believed to have been mixed race. Rodrigues Alves (1902-06) and Washington Luis (1926-30) are also said to have had mixed racial backgrounds, though neither are known to have identified their black heritage.

Perhaps more salient to voters than race, Silva’s personal story points to another way that Brazilians understand diversity in their country. Silva, the anthropologist, says that Marina Silva’s origins in the Amazon resonate strongly with Brazilians because that goes against another sort of prejudice: that if you’re from the vast rural interior of the country, away from its megalopolises, you’re considered less educated, less developed, and generally believed to be “behind."

Silva's association with this geographic region puts her at odds with the ruling PT. Critics say the PT thinks reducing inequality means making consumers out of the poor – rather than, say, citizens with rights. The "Brazilian dream" under the PT is often depicted, ironically, as a favela resident who has a flat screen TV. Silva’s ascent challenges that story, painting a picture of a Brazilian entering modernity while still deeply identifying with the remote and “backward” area she came from.