What helps Haiti? ‘Working with’ versus ‘doing for.’

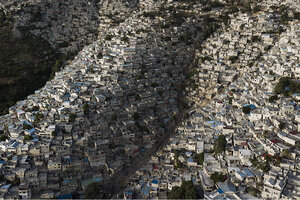

Homes stand densely packed in the Jalousie neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, July 13, 2021. Haitian President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated July 7.

Matias Delacroix/AP

As Jeanne-Baptiste Vania stirred a huge bubbling pot of spaghetti in fish stock at her plot in a burgeoning homeless encampment in Port-au-Prince, she was already thinking beyond her own plight.

It was January 2010, and just days earlier the matriarch of a family of 17 had lost her home in the Haitian capital in a devastating earthquake that had gut-punched the Caribbean island nation when it was already down: The poorest country in the Western Hemisphere was long considered a failed state.

In a matter of seconds, as many as 2 million Haitians were displaced, and several millions more were left without essential services or a source of income.

Why We Wrote This

Have billions in aid left Haiti worse off? Some who know the country say when top-down assistance has been replaced with cooperation plumbing Haitians’ resilience and ingenuity, conditions have improved.

But here was Ms. Vania in the homeless encampment that, before the earthquake, had been the private gardens of the prime minister’s residence. As she spiced her soup, she was set on not just feeding her own family, but imagining how she could ramp up to help nourish “many more desperate souls,” as she called the shellshocked humanity around her.

In the days since the July 7 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse, I’ve thought of Ms. Vania, and the many resilient and determined Haitians I’d met covering the earthquake’s aftermath.

The assassination spawned many stories and much analysis of the decade since the earthquake, with the widespread conclusion that an outpouring of some $13.34 billion in international aid between 2010 and 2020 has left Haiti no better, and probably worse off, than before the horrendous temblor.

The motivations (and actors) behind the Moïse assassination remain murky. But many Haitians say the corruption that intensified as billions of dollars coursed through the country, and the way the earthquake assistance further concentrated power among a few antagonistic elites, were almost certainly factors behind the president’s violent demise.

Yet at the same time, Haiti specialists who are no Pollyannas say that while they agree that much of the foreign assistance has worked in insidious ways to make things worse, they also see where key advancements have been made.

Lessons have been learned, they say. Perhaps the first among them is that when top-down is replaced with “tap into,” conditions improved. In other words, international assistance was more effective when designed to cooperate with Haitians and plumb their ingenuity, know-how, and familiarity with the terrain than when provided from on high and designed to serve the donor nation’s interests.

Thinking back to Ms. Vania: If, instead of just feeding her and her big family, foreign aid agencies and nongovernmental organizations tapped into her resilience, desire to serve, and local knowledge, the mountains of aid had a better chance of actually doing good.

“I compare the kind of aid that generally came into Haiti after the earthquake to a series of ‘aftershocks’ that further hollowed out services and ministries, increased corruption, deteriorated security, and paradoxically even increased violence against women,” says Mark Schuller, an anthropologist and noted Haiti expert at the University of Northern Illinois who is also president of the international Haitian Studies Association.

“But that is not the full story,” adds the author of “Killing With Kindness,” a 2012 study that chronicles how official development aid and NGO work have often undermined Haiti’s progress.

“When the humanitarian impulse to do for has been replaced with a focus on working with,” Professor Schuller says, “and when the approach is one that emphasizes coordination and cooperation with Haitians, it has demonstrated that it can work.”

As examples of this kind of success, he cites the Spanish government aid agency working closely with local utilities and health activists to provide water and sanitation to large camps for displaced persons and to the capital’s Cite Soleil slum; and USAID collaboration with local health agencies and advocates to address the HIV/AIDS crisis and bring down infection rates.

Many experts underscore how it’s not just that foreign governments have deepened Haiti’s woes with top-down intervention, but that many large international NGOs took a similar approach that undervalued local expertise and contributed to deterioration of the Haitian state.

Studies revealed, for example, that only 1% of post-earthquake foreign assistance went to ministries or agencies of the Haitian government – while 99% went to NGOs. While some key ministries such as health were indeed initially knocked out of service by the earthquake, the heavy reliance on international NGOs only exacerbated Haiti’s deinstitutionalization, experts say.

“People can’t understand how Haiti deteriorated to such disastrous conditions, but it’s important to realize that the way foreign actors have interacted with Haiti has really lacked basic humanization,” says Ellie Happel, director of the Haiti Project and adjunct professor at New York University’s Global Justice Clinic.

What the last decade has taught some organizations is that foreign involvement ultimately only is a factor of progress if the guiding principle is collaboration, not “top-down, one-way streets,” she says.

In the Global Justice Clinic’s work with Haitian rights advocates supporting workers in the emerging mining industry, for example, Professor Happel says, “We start from the basis that the people closest to the problem are best placed to come up with the solutions."

Many Haiti specialists say the U.S. focus on working with Haiti’s ruling elites – supporting and propping up Mr. Moïse even as he turned increasingly dictatorial in the two years before his death and relied on the country’s violent gangs to stay in power – has further weakened Haiti.

Professor Schuller has little positive to say about U.S. assistance to Haiti, noting that first and foremost it is aimed at promoting U.S. foreign policy interests: for example, he says, providing quick fixes that stabilize the population and avoid a mass migration by Haitians to America’s shores, but doing little to address Haiti’s long-term needs.

And many critics say the United States is compounding past mistakes by insisting Haiti move to elections before the end of the year to fill the political power vacuum left by Mr. Moïse’s assassination.

“Free and fair elections are just not possible in Haiti today, and the U.S. doubling down on elections is only going to perpetuate the problems that accumulated under Moïse,” says Professor Happel, who lived in Haiti for six years.

At a congressional hearing last year, she testified that three main factors make rushed elections more of a problem than a solution: insecurity and heightened gang control in recent years, an incomplete voter ID system rollout, and widespread distrust of election legitimacy.

Many Haitians and experts on the ground say elections anytime soon make little sense and could actually increase already high levels of violence, given several factors: the government’s branches are emptied, and there are deep divisions over how to fill them; before his death, Mr. Moïse had been ruling by decree; there is no functioning parliament; and the president of the Supreme Court died last month after being diagnosed with COVID-19.

Instead, many in Haiti’s civil society are calling for the creation of a transitional government to focus on immediate humanitarian needs and stabilizing Haitian society before holding national elections.

And Professor Happel advocates listening to the nascent Commission for a Haitian Solution, a group of more than 100 civil society, religious, and labor organizations calling for Haitian society to focus first on inclusive national dialogue aimed at finding solutions to the country’s big problems.

“It would be a real effort at consensus building,” she says, “bringing in all of Haiti’s actors and based on that idea that those closest to the problems are best suited to come up with the solutions.”