Peru protests highlight rural-urban divides – and a desire to belong

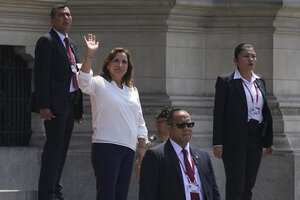

A demonstrator waves Peru's flag as security forces stand guard during a protest in Lima, Peru, on Jan. 12, 2023. Protesters are demanding the dissolution of Congress and new democratic elections, following the ouster of former leftist President Pedro Castillo, who is accused of attempting a coup last December.

Alessandro Cinque/Reuters

Lima, Peru

Peru is living through its worst conflict this century, and the scenes in many ways are reminiscent of its internal conflict of the 1980s and ’90s: Indigenous villagers carry coffins through the streets, parents wail for children taken too soon, and human rights groups decry excessive government force.

The wave of violent anti-government protests, sparked when interim President Dina Boluarte took office last month, also highlights historic dividing lines in Peru: between the rural, mostly Indigenous poor, and the ruling elites in the capital, Lima.

Many protesters support former leftist President Pedro Castillo, who was arrested in December for trying to illegally take control of Congress and the courts. Mr. Castillo is the son of illiterate farmers from a poor Andean region, and despite his transgressions, he is someone many protesters in rural and Indigenous Peru identify with. Instead of seeing him as a would-be dictator, they see him as the victim of racist elites who never wanted to share power with him – and by extension, them.

Why We Wrote This

Polarization and protests have flared around the globe. In Peru, current unrest falls along historic rural-urban rifts – pointing to a yearning for political inclusion.

Now, they are agitating for President Boluarte’s resignation, the closure of Congress, new general elections, and a new constitution. As death tolls climb, reaching 50 victims nationally since protests exploded in December, the need to identify a peaceful path ahead, starting with healing historic divisions, has grown more urgent.

“We feel we’re hated by those who govern Peru,” says Lucas Pari, a representative of the National Union of Aymara Communities, which supports the protests. “That hatred was always there, but now people are getting organized to demand respect for our fundamental rights to life, to equality, and to our identity.”

“Equal citizens”

At the heart of the current crisis is a long-standing division between those living in the capital, Lima, and rural and Indigenous Peruvians who have faced historic marginalization. Southern Andean regions tend to prefer anti-establishment politicians promising big change, and have produced several campesino uprisings.

After Peru’s independence from Spain, Peruvian campesinos continued to toil as indentured servants on plantations owned by elites up until 1969, when a leftist dictator redistributed land. Many were barred from voting for another decade due to literacy requirements, and scores of communities in Peru’s southern Andes were caught in the crosshairs of bloody battles between leftist insurgents and state security forces and paramilitary groups. Despite a rapid economic expansion during the commodities boom in the early 2000s, extreme poverty has persisted in many rural villages, which frequently lack access to basic sanitation, paved roads, schools, and hospitals.

The pandemic further exposed Peru’s geographic inequality. When the government imposed a strict lockdown, thousands of migrant workers in Lima and other urban hubs were left to trek home en masse after losing their jobs.

Though he had no prior experience governing, Mr. Castillo promised to remedy historic injustices with a new constitution and heavy spending on health and education. Instead, his 16 months in office were marked by corruption scandals, political and managerial missteps, and growing polarization as he blamed his troubles on Lima elites, many of whom tried to overturn the results of his election with unfounded claims of voter fraud.

“When people in Lima saw Castillo’s sombrero they said, ‘No, the son of an illiterate farmer!’ But here people felt ‘he’s one of us. He’s on our team,’” says Rolando Pilco, an anthropologist from Puno, who is Aymara.

Mr. Pilco says the lack of Indigenous representation in national politics is part of the problem. Unlike neighboring Bolivia, where former President Evo Morales passed a constitution that empowered Indigenous groups and introduced quotas for Indigenous representation in Congress, in Peru decision-makers are disproportionately part of the country’s white and mestizo elite.

“People want change. They want to feel like equal citizens in the country,” he says.

Deepening the fury

While Ms. Boluarte was elected alongside Mr. Castillo as his vice president, many who once voted for her now see her as a traitor. They remember her promises to resign when Mr. Castillo faced his first impeachment attempt five months into his administration, and they criticize her for forming a center-right Cabinet backed by Congress, the least popular institution in the country.

A shocking spate of deaths in clashes between security forces and protesters in regions outside of Lima has only deepened the fury.

Last month, protesters blocked dozens of roads, attacked regional airports, and vandalized prosecutors’ offices, courthouses, and factories. Protests were suspended for the holidays but resumed on Jan. 4, and over the past week, the death toll doubled to 50, according to the country’s ombudsman’s office. The worst of the violence unraveled in Juliaca, a highland town in the region of Puno, near Lake Titicaca and the border with Bolivia.

There, in a single day of clashes between police and protesters trying to take control of the airport, 17 civilians were killed, all shot with projectiles from firearms, including multiple bystanders.

“We just want to live in peace,” says Jakeline Zapana, the head of a local animal rights group in Juliaca. One of her group’s young volunteers, Yamileth Aroquipa, was shot dead while making her way to a local market when clashes broke out.

Ms. Aroquipa was 17 years old, bilingual in Spanish and Quechua, and had just started studying psychology. “We’re all in shock,” says Ms. Zapana, who isn’t hopeful military or police officers will be held accountable. The deaths of protesters – especially when they are killed far from Lima – are rarely solved, she says.

The massacre in Juliaca was “the largest registered attack [on] civilians by police since Peru returned to democracy,” says Jo-Marie Burt, a human rights advocate and professor at George Mason University in Virginia. Police are “shooting to kill, aiming at the heads and upper bodies of protesters,” she says.

Ms. Boluarte’s government says it didn’t give orders to fire on protesters and would cooperate with prosecutors. But, in a late-night message to the nation on Friday, she blamed radicals for stirring up unrest, comparing recent vandalism at protests to terrorist attacks by the Shining Path insurgency in the 1980s and ’90s.

“The only way” to take part in politics?

Thousands of Indigenous people were “disappeared” by government-backed death squads without trial during that time period, and for many living in these historically repressed areas, the comparison to the Shining Path was deeply offensive. It’s part of the stigmatization of leftists and Indigenous people that many in Peru have embraced since its return to democracy in 2000.

“We’re not terrorists. We’re people who know that this system has to be changed to bring true representation,” says Janyce Garcia, a protester in her late 50s, marching alongside thousands of demonstrators in Lima on Saturday.

As protesters made their way through Lima’s upscale district of Miraflores, some locals shouted “communist” and “terrorist” at them. A man told a truck full of riot police officers to “burn them all,” referring to the protesters.

“These messages are not innocuous. On the contrary, they contribute to creating an environment of permissiveness and tolerance towards discrimination, stigmatization, and institutional violence against this population. Especially when they come from public authorities,” said Stuardo Rolán, the head of an Inter-American Human Rights Commission delegation that visited Peru last week.

In times of political crisis, peaceful protests can be “the only way for communities that face structural discrimination or political and social exclusion to take part in politics,” he said in a press conference.

Initial hopes for dialogue to end the crisis have faded amid growing polarization. Counterprotesters have launched “marches for peace,” backed by the police, occasionally clashing with demonstrators.

Ms. Boluarte proposed early elections for April 2024, but doing so requires a constitutional reform that lawmakers are reluctant to pass. That has led to growing calls for Ms. Boluarte’s resignation, which could force Congress to schedule a new vote without the need for reforms.

Even with new elections, high levels of polarization could lead to a result similar to the outcome of the 2021 vote, when Mr. Castillo faced a far-right politician in a divisive runoff race.

“There is no promising scenario,” says Peruvian political analyst Fernando Tuesta. “But elections are always an opportunity.”