Falklands again? Why Argentina's Kirchner keeps pushing the issue with Britain.

Kirchner's populist platform targets debt reduction, social inclusion, unorthodox economic policies, and repeatedly pressing Britain over the South Atlantic archipelago.

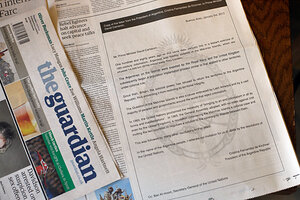

In this photo illustration, a copy of the Jan. 3 issue of the British national newspaper The Guardian shows an open letter published as an advertisement from the president of Argentina, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, to British Prime Minister David Cameron about the Falkland Islands (called the Malvinas Islands by Argentina).

Alastair Grant/AP

Buenos Aires

Argentine President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner relaunched her offensive over the Falkland Islands today, a move that coincides with the 180th anniversary of Britain’s allegedly illegal usurpation of the South Atlantic archipelago.

Ms. Kirchner published an open letter to British Prime Minister David Cameron in British newspapers imploring him to respect a United Nations resolution that calls on the two countries to negotiate sovereignty of the Malvinas, the name for the islands in Spanish.

Britain has repeatedly refused to enter into talks, and a spokesman for Mr. Cameron responded by saying he will “do everything to protect the interests of the islanders.”

But Kirchner's move forms part of a broader leadership pattern that has seen the nationalist president take on so-called vulture funds, demonize the International Monetary Fund, and echo Hugo Chávez’s anti-neocolonial discourse.

'National and Popular'

Though Britain may take the view that Kirchner is beating a dead horse, the Falklands are a longstanding national cause for Argentina and are written into its Constitution. Today's letter represents what are described here in Argentina as "Nac & Pop" policies.

"Nac & Pop" stands for national and popular, the way Kirchner defines her government. She casts reclaiming the Falklands, over which Britain and Argentina fought a short war in 1982, as a South American struggle against neocolonialism.

Britain recently named a slice of Antarctica over which Argentina also has a claim "Queen Elizabeth Land," a move branded by a source at the Argentine presidential palace as “provocative and childish.”

“If it occurs to the British Empire to attack the Falklands, Argentina won’t be alone this time,” Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez said last year. With Chávez’s future uncertain due to recent health concerns, Kirchner could be trying to position herself as the leader who replaces him as the resounding voice of the South American left.

Kirchner also made a stand over the Falklands at the UN’s decolonization committee last year, and sanctioned a controversial TV commercial showing an Argentine field hockey player training for last summer’s London Olympics in Port Stanley, the islands’ capital.

The populist methods sit well among her supporters, who parade “The Malvinas are Argentine” flags at government rallies. And given that Kirchner's approval rating has dipped to roughly 35 percent – a decline of about 30 percent – in opinion polls since her reelection in October 2011, playing the Falklands card is viewed by some analysts as a way to halt that slide.

Beyond the Falkland Islands

Aside from the Falklands, Kirchner’s debt-reduction plan – accompanied by interventionist economic policy – and push for social inclusion are the pillars of her national and popular policies.

Next week, the Fragata Libertad – a ship embargoed in Ghana by an American-based holdout creditor that is demanding payment after having rejected debt exchanges on the back of Argentina’s 2002 default – will arrive at Mar del Plata, a city in Buenos Aires province.

Kirchner will be there to receive it. In her bid to reestablish Argentina’s economic sovereignty, she accused an American judge of “judicial colonialism” after he recently ruled that the holdout creditors should be paid.

The economy and the Falklands are both essential to Kirchner’s "Nac & Pop" strategy, and are likely to continue to be used for political gain.