North Korea shows off its grandeur – and 'life as usual'

Empty streets and shops belie the image of success that a tightly controlled tour of Pyongyang tries to project.

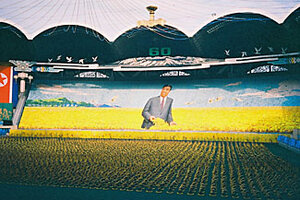

On display: At the annual Arirang Festival, 50,000 people carryingplacards in May Day Stadium shift from one scene or slogan to the next,trumpeting the nation’s successes; 50,000 others perform in sync on thefield.

Donald Kirk

Pyongyang, North Korea

A tour guide erupts in anger when asked about the physical condition of "Dear Leader" Kim Jong Il.

"That is all foreign propaganda and lies on BBC and CNN," says Oh Keum Suk, dismissing with an angry wave the notion that Mr. Kim, said by US and South Korean intelligence sources to have been partially paralyzed by a stroke, is in anything but great health. "He is fine, excellent."

It is the height of the tourist season in this isolated capital, when foreigners are admitted on scrupulously controlled visits. Those whom visitors get to see are primed to present an image of normalcy, of progress and success, in the face of dark forces swirling about the country.

"Let us open the door of great prosperity and a powerful civilization," says the huge lettering emblazoned across one side of the stands by thousands of young people holding placards that shift from one scene or slogan to another. "Enthusiastic and optimistic era," says the next sign as thousands of costumed performers prance and pirouette below in May Day Stadium.

At the annual Arirang Festival, tourists witness an astounding display of synchronized energy involving some 100,000 people. The show goes on four nights a week for three months – each performance a 90-minute tribute to triumphs in war and development, all attributed to the leadership of Kim and his father, "Great Leader" Kim Il Sung, who died in 1994.

The show assumes more significance than usual this year. On either side of the stands, in lights, are the years 1948 and 2008: It's the 60th anniversary of the founding of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, the North's formal name. The fact that Kim Jong Il did not attend the parade marking the event, even though he was present at the 50th anniversary, is a detail that goes unnoted, at least publicly.

Publicly, the country focuses on yet another date, April 15, 2012, the 100th anniversary of the birth of Kim Il Sung. Anticipation of the date appears to have motivated a wave of construction in a city dominated by huge edifices, museums, and monuments, most of them dating from the first few decades after the devastating Korean War. "We must build our city to follow Kim Il Sung's ideal," says a senior guide, Choe Jong Hun, an officer in the cultural exchange department.

The broad empty boulevards, of shops that appear to be virtually empty of products or customers (from the vantage of a tourist van that stops at none of them), the reports of periodic crackdowns on free-marketeering and of pervasive bureaucratic meddling and spying belie the appearance at the spectacle.

Mr. Choe adopts a carefully modulated view when asked about reports warning of an incipient crisis on a scale, in some regions of the country, with the famine of the 1990s.

"We face economic problems," he says, choosing his words carefully. "There is a shortage of food, electricity."

But he reverts quickly to a more roseate view. "As you see, our city is dignified and beautiful and calm," he insists. "That is the difference between European cities and our city."

Beneath the calm, Western diplomats here say they have seen little real change in official outlook over the past two or three years. "The regime is about survival," says an ambassador. "Everything is done to perpetuate its existence."

Toward that end, he says, the regime has actually reversed a limited experiment in free enterprise, shutting down markets where farmers sold goods. Women under the age of 50 are said by foreign diplomats and aid workers to be banned from certain markets, for fear they will aggressively demand the right to buy goods for their hungry families.

In June the government appeared to have adopted a more open attitude toward efforts of the World Food Program to channel food to those who needed it most. "We had excellent cooperation and access," says Jean-Pierre DeMargerie, director of the program here.

Lately, however, he's discovered more bureaucratic resistance, even as food supplies dwindle before the harvest season next month. "You have to adjust expectations," he says. The country remains "by far the toughest place to work with."

One reason for the shift may be official anger over the refusal by President Bush to remove North Korea from the US list of state sponsors of terrorism until the North agrees on a protocol for verifying all it claims to have done to end its nuclear weapons program.

"It's Bush's responsibility for not keeping his word," says guide Oh Keum Suk. "It's not our problem if the US says we are a terrorist country."

He's less forthcoming about whether the North has resumed developing nuclear warheads, as officials have been saying. "We must discuss problems in an international way," he says.