Visiting Russia, Kim Jong-il casts nervous eye on Tripoli

North Korea's Kim Jong-il is visiting Russia to bolster diplomatic support. A key issue is the ability of Kim's son and heir to rule with an iron hand – an issue getting renewed attention as Libyan rebels advance into Tripoli.

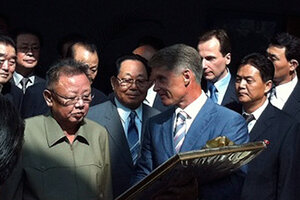

North Korean leader Kim Jong-il receives a painting during a welcoming ceremony upon his arrival in Novobureyskaya, Amur province, Aug. 21. Mr. Kim visited one of Russia's largest hydro power stations on Sunday, part of a tour of the country's Far East before talks with President Dmitry Medvedev, Russian news agencies said.

www.portamur.ru/Reuters

Seoul

North Korea’s leader Kim Jong-il, visiting Russia this week, is looking for political and diplomatic support from Russian leaders amid questions about his third son’s ability to succeed him – and the possible impact of uprisings in the Middle East on stability in his own country.

While Mr. Kim looks at power plants as his armored train takes him to the summit in Siberia with Russian President Dmitry Medvedev, the view here is that he wants much more than a deal for electricity or natural gas.

At the top of his concerns, say analysts, are the implications of the downfall of Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi on his plans to perpetuate his dynasty.

“That dynamic is probably much more alarming to Kim Jong-il than anything else,” says Lee Jong-min, dean of international studies at Yonsei University here. “He’s prompted by the need to bolster his power.”

Although the North Korean media shield most of the country’s 24 milliion people from news about the Middle East, word of rebellion seeps through via clandestine radios and word of mouth from people who cross the Tumen and Yalu river borders into China on illicit trading expeditions.

It’s because of the fear of revolutionary fervor spreading to North Korea, says Mr. Lee, that Kim is anxious to convince Russian leaders that his third son, Kim Jong-un, in his late 20s, is strong enough to be able to rule a populace enervated by years of famine and disease.

“His visit is all tied to succession in North Korea,” Lee goes on. “He wants to buff up his son’s standing. That’s the major driver.”

Balancing Russia and China

Kim’s visit seems especially portentous, moreover, considering that he’s visited China five times since he last journeyed to Russia in August 2002 for a meeting with Russia’s Prime Minister Vladimir Putin.

North Korea has won China’s possibly begrudging endorsement of Kim Jong-un as heir to power along with promises of a steady flow of supplies to keep the regime on life support.

Kim is assumed, however, to want to counterbalance China’s enormous influence with that of Russia, which shares a 12-mile border with North Korea as the Tumen River flows into the sea – and during the era of Soviet rule was a major ally and aid giver.

Although Russia has taken a secondary role since the breakup of the Soviet Union two decades ago, Kim would like to reach a deal for electrical power and possibly natural gas and other aid that’s badly needed to build up the North’s dilapidated economy.

At the same time, a closer relationship with Russia would free the North to some extent of near-total dependence on China.

The North Korean leader also is believed to want to get Russia behind moves toward renewing six-party talks on the North’s nuclear program.

“North Korea and China both say they want six-party talks,” says Kim Tae-woo, a military analyst and president of the Korea Institute for National Unification. “He wants to add Russia to the list.”

Beyond that, says Kim Tae-woo, “He needs some declaration from Russia of North Korea next year as "a strong and great nation.”

That term, he notes, has become almost a slogan as North Korea gears up to celebrate Kim Jong-il’s 70th birthday in February and the 100th anniversary in April of the birth of his long-ruling father, Kim Il-sung, who died in 1994. The build-up for those dates helps explain North Korea’s global campaign for aid donations from just about every possible source.

North Korea this month is receiving $4.5 million in aid for flood relief from South Korea and $900,000 from the United States. Amid renewed talks, the thinking is that US and South Korea aid, cut off after the South’s conservative president, Lee Myung-bak, was inaugurated n early 2008, might increase as tensions ease in the aftermath of two incidents last year in the Yellow Sea -- the sinking of a South Korean Navy vessel and the shelling of Yeonpyeong Island, in which a total of 50 people were killed.

The North Koreans “want to seek economic assistance from the outside, possibly from the United States,” says Kim Tae-woo. “Kim Jong-il is trying to get more from Russia. And then they are trying to balance between Russia and China. They may be seeking leverage against China.”

All the while, North Korea faces the fear of repercussions of “the jasmine revolution.” Reports of discontent in the form of sub rosa criticism of the regime, of defiance against officials and occasional isolated acts of violence are heard here in risky cellphone calls and other stories told by rising numbers of defectors.

“That’s why,” says Kim Tae-woo, “the North Koreans need to tighten their control internally.”