Witness to a decade that redefined Southeast Asia

As he leaves his post in Bangkok, a correspondent looks at how a rising China has changed the Southeast Asia region after 9/11.

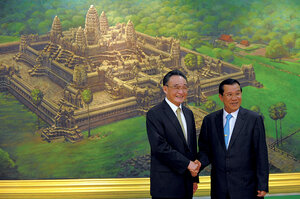

Senior Chinese official Wu Bangguo (l.) with Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen in Phnom Penh last year. Even as they embrace China, many Southeast Asian nations have questions about how it will project its power long term.

Tang Chhin Sothy/AFP/Newscom

Bangkok, Thailand

It was the summer of 2001. I was covering an election in East Timor, a newly minted nation at the end of the world. It was my first assignment for the Monitor, the start of a decade of reporting in Southeast Asia, filing hundreds of stories from across a diverse region of 600 million people.

Two years earlier, East Timor had broken free of Indonesia's brutal occupation. It now aspired to join the ranks of global democracies, including the mightiest of all, the freedom-loving United States. Never mind that Washington had backed Indonesia's dictator General Suharto and other Asian strongmen. The cold war was over, Suharto was gone, and Southeast Asia's tiger economies were roaring again, all under the protection of the US security umbrella.

Not long after, the geopolitical world spun on its axis.

First came the shocking attacks of Sept. 11, which redefined US foreign-policy goals. Exactly three months later, China joined the World Trade Organization, an economic milestone. The pace of China's exports soared, and its dollar reserves began piling up.

To my mind, we're still living in the shadow of these two historical markers.

Both events have had lasting consequences in Southeast Asia, where a resurgent China has begun to chip away at decades of US preeminence in trade, aid, and diplomacy. Some countries are firmly in China's sphere of influence: Cambodia, Burma (Myanmar). Others are hedging their pro-US stance: Thailand, the Philippines. Only Vietnam appears to be rowing in the opposite direction by embracing Washington, its former enemy.

Of course, China's economic rise predated Al Qaeda's attacks on US soil. It makes sense for Southeast Asian leaders to bind their economies to China's and to cooperate on other issues. Once again, China is becoming the center of gravity in Asia.

But the perception in Asia was that Washington was too distracted by waging wars to raise its game vis-à-vis China. President Bush was a no-show at regional summits, and his envoys didn't come bearing bilateral trade deals or new investments as Chinese leaders did.

Instead, they talked terrorism, security, and Islam, and were viewed with deep suspicion by Muslims in the region.

China's 'strong benign partner' approach

China wants to be seen as a "strong benign partner" to the region, a Malaysian defense strategist told me in 2005.

"What's less certain is that once China becomes that strong power and sits, let's say, shoulder to shoulder with the US, how will it behave then?" he asked.

That question still echoes through the corridors of power in Southeast Asia. China has begun testing its first aircraft carrier, while pressing its claims to islands in the South China Sea. The debt-saddled US economy is underwater. The rising-China/declining-US narrative has become a global talking point.

Yet on the streets of Bangkok and Singapore, the mood is more upbeat. Many people have Chinese roots and are proud to see China back on its feet. Others are simply happy to get a piece of the action as China's economy sucks in more goods and services from the region.

On the outskirts of Bangkok, I spent a day with Varnee Ross, the daughter of a Thai-Chinese tycoon. Her private school caters to elite Thais who want to prepare their kids for a more Chinacentric world. In the classroom, I heard young children chant in Mandarin, then switch to English in their next class. During recess, they revert to their native Thai.

English is still the global language. But Mandarin is making rapid inroads, particularly in countries that trade heavily with China.

Last year, China bought around $40 billion in goods from Thailand, more than from Japan, Europe, and the US. Not surprisingly, Thai professionals see learning to speak Mandarin as a way to get ahead.

Ms. Ross told me she had a more romantic vision for her trilingual school.

"I would like my children to appreciate beautiful poems and beautiful Chinese paintings," she said.

Indonesia's relationship

Indonesia has a more fraught history with China, and with its ethnic-Chinese minority. After crushing a Communist movement, Suharto cut ties to Beijing and made it illegal to distribute Chinese-language books. The ban was lifted in 2000, but Chinese-Indonesians, who tend to be richer, still face popular prejudices.

Radio Cakrawalla, an FM station in Jakarta, serves up a diet of Chinese pop music and Mandarin chatter. Its young presenters, like Rudy Xiao Wei, have studied overseas in Chinese-speaking countries and returned to a democratic Indonesia, eager to explore new freedoms.

"When you broadcast in Mandarin, you get a lot of old people, but also teenagers who want to learn," he told me as we sat in the studio, watching call-in messages scroll on a monitor.

Yet Radio Cakrawalla is a strictly minority taste. Spin the dial in Jakarta or Kuala Lumpur and you'll hear mostly American music, just as the multiplex is a showcase for Hollywood movies. Chinese films barely get a look-in, apart from martial arts epics. Instead, the competition is from South Korean and Japanese TV shows and boy bands.

China may be a trading behemoth, but it doesn't set the cultural agenda.

A little Mandarin, a little Ivy League ...

The same applies to education. Thai parents want their children to speak Mandarin. But a degree from an Ivy League school is still prized, says Ross, who graduated from Fordham University in New York. Vietnam ranks in the Top 10 countries of origin for foreign students in the US. Singapore is trying to become an education hub by hosting Western universities, including Yale University. Such is the nature of soft power.

Democracy is another asset for US imagemakers. Southeast Asia isn't a bastion of political liberty, but most countries have some kind of elected government, and young people are demanding far greater freedoms than those of their parents' generation, which focused on economic survival. I rarely meet anyone who views China's political system as a model for their own country.

Even in Muslim-dominated Indonesia, where Bush-era wars were so unpopular, America's image got a boost from the election of President Obama, who spent part of his boyhood there.

The US government has also learned to balance its support for counterterrorism in Indonesia, which has suffered its own Al Qaeda atrocities, with more outreach to ordinary Muslims who are moderate in their faith, yet suspicious of US influence.

The latest effort was a series of concerts this month in Indonesia by Native Deen, an Islamic hip-hop group from Washington. Their four-city tour was billed as a "diplomatic mission" to promote tolerance, all paid for by the US State Department.

China is taking note. It has begun flying Indonesia's Islamic scholars to China on study tours in order to show how Muslim minorities thrive in China, despite its official atheism. It's the kind of public diplomacy that the US has used for decades to burnish its image, so it's hardly surprising that China is doing the same.

It may be in this area, as well as the "hard power" of military might and economic influence, that US-China rivalry plays out in Southeast Asia in the decades ahead.

I won't be around to watch this contest of ideas in Southeast Asia. I'm waiting for my journalist accreditation from Beijing, where I'll be working as a business reporter. I'll miss this region and its beguiling mash-up of people, cultures, and languages.

Now please excuse me while I get back to my Mandarin homework.