Will China be forced to change its secretive leadership process?

Profound disarray ahead of the key Chinese Party Congress is leading to speculation that a selection process once dominated by a single strong leader will have to become more competitive.

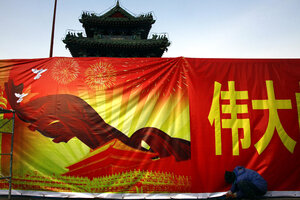

A worker installs a propaganda banner, promoting the Communist Party Congress, outside the 700-year-old Dongyue Temple in central Beijing Nov. 5. China is set to promote two rising stars and possible future national leaders at a Communist Party Congress opening this week, one taking the old job of disgraced former highflier Bo Xilai in the country's biggest metropolis, sources said.

David Gray/REUTERS

Beijing

Never again, after this week’s party congress, will China’s ruling Communist Party select its top members through the secretive, confusing, and mistrustful conversations in smoky back rooms that have led to such disarray this year.

That is the view of Chinese analysts familiar with the inner workings of the party, who say that as proliferating interest groups complicate leadership transitions, party members are increasingly angry at being left out of the leadership selection process.

Just days before the 18th Party Congress opens on Thursday at the Great Hall of the People on Tiananmen Square, the most important political meeting for a decade, varied rumors continue to swirl over just who will be named to the Communist Party’s top policymaking body, the Politburo Standing Committee. It is not even certain how many members the body will have.

The unprecedented confusion indicates that “the highly chaotic, black box … negotiating process carries high costs, is highly uncertain, and is very violent,” says Wu Qiang, who teaches politics at Beijing’s Tsinghua University. “They cannot go on like this.”

There was a time when outgoing Chinese leaders were strong enough to name their successors, and that put an end to any discussion. Mao Zedong named the man who took over after his death, and later, “Supreme leader” Deng Xiaoping had the authority to choose not only his own successor, but the man who succeeded that successor – the now-outgoing General Secretary Hu Jintao.

In today’s China, however, where the Standing Committee has come to rule mainly by consensus, no individual has such power.

“Deng was the last one with absolute legitimacy because of his role in the revolution,” says Michel Bonnin, a China expert at the French School for Advanced Social Science Studies. “Today, there is no one like him.”

Behind closed doors

But the party has not developed any other convincing manner of choosing leaders and endowing them with legitimacy. “There is no voting, and no rule-based way of measuring popular opinion in the party,” points out Zhang Jian, a politics professor at Peking University. “If you don’t have a strongman or democracy, you are in a mess. Anybody can compete.”

Xi Jinping, almost certain to take the top job from Mr. Hu at the end of the week-long congress, emerged from negotiations among rival factions five years ago, but has little personal authority yet. Only one other man is staying on the Standing Committee, Li Keqiang, expected to be named premier.

Battles for the remaining five – or seven – places are still said to be raging behind closed doors, complicated by the fallout from the unprecedented public challenge to the party leadership that Bo Xilai mounted before he was brought down and expelled from the party. He is now awaiting trial, accused of corruption and involvement in a murder for which his wife is already serving a jail term.

But Mr. Bo’s fate, and the fate of those close to him, is not the only complicating factor this year, says Wang Zhengxu, deputy director of the China Policy Institute at Nottingham University in Britain.

“There is a much more diverse range of regional and policy preferences” at stake, as different economic and social interest groups fight for representation at the party’s highest levels, says Professor Wang.

Unwritten rules of China’s leadership

To a certain extent, the party has institutionalized aspects of its once-in-a-decade leadership transitions. For one thing, party congresses have been held regularly every five years since 1977. Under Mao Zedong, the party went 13 years after 1956 without meeting.

Unwritten rules dictate that top officials should not serve more than two five-year terms, and that they should step down when they reach the age of 70. Straw polls among the 400 or so most senior party members and retired elders are used to gauge opinion about potential leadership candidates, though their results are kept secret.

But the process of choosing the next generation of leaders is dominated by a series of secret deliberations among small groups of top officials, each representing different factions within the party, whose horse-trading and dealmaking is hidden from everybody else’s view.

‘The system is nearing its end’

That such negotiations over the next Standing Committee appear still to be under way suggests that though “this time they will muddle through … this system is nearing its end,” says Wang. “When things become really unmanageable, they will have to change the rules,” he predicts, perhaps by making the straw polls “more binding than the consultative elections that they are now.”

For two decades after the massive demonstrations on Tiananmen Square in 1989, top party leaders “built a strong consensus that they had to show solidarity with one another because it was a matter of life and death,” says Professor Bonnin. But time has worn that consensus away. Now, worries Professor Zhang, “power struggles at the top are becoming more unprincipled.”

The results, he points out, became clear in the debacle surrounding Bo. But even when the factional rivalry is kept discreet, it is no less fierce as Mr. Xi, Hu, and former President Jiang Zemin all try to ensure places for their allies on the Standing Committee.

The danger, Zhang warns, is that if individual members of the committee are chosen in political deals sealed to end violent clashes, rather than by more considered consensus, “they will find it hard to work together.” And those that lose a policy debate in the Standing Committee might even be tempted to use their followers within the government bureaucracy to hinder the execution of the policy.

Such problems, says Liu Shanying, an analyst at the China Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing, derive from the fact that “the leadership transition system is itself in transition” from the traditional strongman-dominated process to a “more multilateral competitive process.”

“We are in the middle of this transition,” he believes. “When it is completed, there will be more standard procedures” for choosing China’s leaders, which will be “more open, more transparent and more democratic.”

Just what those procedures might look like, Professor Liu says, is still unclear. For the time being, smoky backrooms are still the key setting for all that matters in Chinese politics.