Chinese power play: Xi Jinping creates a national security council

The council's creation is seen as strengthening the position of President Xi Jinping, giving him a freer hand to address domestic and international crises.

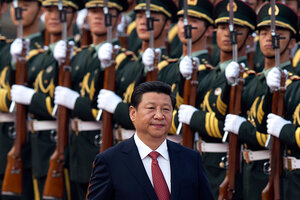

Chinese President Xi Jinping inspects a guard of honor outside the Great Hall of the People in Beijing Aug. 26, 2013. China's plan to create a new security council, Wednesday, Nov. 13, further consolidates power behind President Xi Jinping in the years going forward.

Andy Wong/AP/File

Beijing

One line in the 5,000-word statement issued at the end of a key meeting of the Chinese government’s ruling core this week has sparked a flurry of speculation.

In the statement, China announced that it is setting up a National Security Council, and everyone wants to know why.

There has been no detailed explanation of the need for the body or why it is being established now, but today a government spokesman indicated the new commission would have a wide focus, including domestic affairs.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman Qin Gang told journalists the new body is “to ensure the nation’s security.”

“That should make terrorists, extremists and separatists nervous. Anyone who would disrupt or sabotage China’s national security should be nervous,” Mr. Qin told a regular press briefing, according to wire service reports.

The actual communiqué, which is heavy on rhetoric and light on detail about plans for economic and political reform in the coming decade, said simply: "A national security committee will be established to perfect the national security system and national security strategy and safeguard national security.”

Analysts say China has long planned to establish such a body to respond to both domestic and international security issues, from border and territory disputes to attacks like the recent car bomb at Tiananmen Square. How far its reach will extend into surveillance and boosting China’s already heavy domestic security controls remains the great unknown.

The commission will likely function like the US National Security Council, and further consolidate power behind President Xi Jinping in the years going forward.

Shi Yinhong, director of Center on American Studies at Renmin University in Beijing, said the idea first arose under President Jiang Zemin more than 15 years ago, but only Mr. Xi has been able to consolidate the necessary power and support to make it happen.

Timing also plays a big part in the decision. China’s rapid growth as a global player and a series of controversial disputes with neighbors over islands and territorial waters have highlighted the need for a centralized advisory body. In addition, the country still wants to keep tight control over regions, including Tibet and Xinjiang.

“In recent years, China has been facing a more complex situation both within and outside China,” says Mr. Shi. “The rise of China faces more challenges and tasks. It needs a system and ‘the top’ to coordinate and oversee making and implementation of policies in an efficient way.”

As for the rest of the communiqué, released at the end of the four-day “Third Plenum,” which typically establishes blueprints for government work over the next decade, even financial markets were unimpressed with the contents.

Some analysts had expected hints of reform, but the plan appears to promise more of the same, with a heavy linguistic focus on “deepening” existing reforms. The document includes almost no specifics about how the central government will manage economic and political reforms going forward, but does indicate that China plans to stay the current course. The government is also promising a bigger role for market forces in the economy, but did not specify how.

Ye Tan, an economist and commentator based in Shanghai, said the most important aspects of the communiqué include a promise of more rights for farmers, particularly land rights. That will be key moving forward as China transitions from a rural to urban society.

The communiqué intends to “shape a new urban-rural relationship that town and country become one,” says Ms. Ye. “Farmers should be endowed with more property rights. It also stresses the core position of the public-ownership economy.”