China extends Japan a helping hand to resolve North Korea abductions

After the North backtracked on its promise to investigate within months the fate of Japanese abducted decades ago, an apparently impatient China said it would host a meeting next week between the two countries.

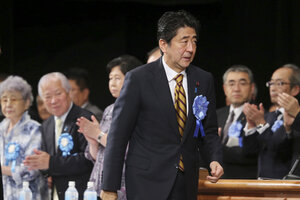

Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe arrived for a rally against North Korea's abductions, in Tokyo Sept. 13. Prime Minister Abe told the rally that he will not back down until every abductee is accounted for.

Koji Sasahara/AP

Beijing

China is setting aside its territorial rivalry with Japan to lend Tokyo a hand in resolving one of the oddest mysteries of the cold war.

The Chinese will host a meeting next week between Japanese and North Korean officials at which Japan will press Pyongyang to explain what happened to the Japanese citizens whom North Korean agents allegedly abducted 35 years ago.

The North Koreans promised last May to reopen an investigation into their fate, saying they would have answers within a few months. Last week, they backtracked, saying they would instead need a year to release a report.

Now the Chinese, North Korea's only ally, appear to be losing patience with foot-dragging by the country's young leader, Kim Jong-un. They will convene the meeting in the northern city of Shenyang, near the border with North Korea, Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida said in New York on Wednesday.

“We need to hear what the current situation is surrounding their re-investigation,” Mr. Kishida told reporters.

The fate of the young Japanese kidnapped from lonely beaches and quiet lanes by North Korean spies resonates deeply among Japan's public. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who has long been involved with Japan's quest to resolve the abductees' fate, has pledged to account for them before he leaves office.

Tokyo officially lists 17 people as abductees, though officials say privately they believe Pyongyang was responsible for many more disappearances in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The North Koreans appear to have kidnapped their victims in order to make them teach Japanese culture and language at spy schools, but the reasons for the mysterious disappearances have never been clarified.

North Korea returned five of the abductees in 2002, claiming that eight others had died and four had never entered the country.

When Pyongyang offered to look afresh into the matter, Tokyo agreed to lift some sanctions it had imposed – removing an entry ban on North Korean citizens, relaxing an embargo on North Korean ships in Japanese ports, and softening financial transfer limits.

No explanation for delay

North Korea’s newfound reluctance to provide information on the abductees looks to many observers like an effort to win more concessions from Tokyo on sanctions, in return for a report. In its message last week to Japan, it simply said: “We aim to complete the investigation in about a year and we are now in the initial stages. As of now we cannot provide an explanation beyond this stage.”

China has become increasingly frustrated with North Korea in the wake of a third nuclear test in February 2013 and the dramatic execution last December of Jang Song-thaek, the president’s uncle and an adviser with close ties to Beijing.

In July, President Xi Jinping broke with tradition when he made a state visit to South Korea, his maiden trip to the Korean peninsula. Previous Chinese leaders always put Pyongyang first.

A top official of the ruling North Korean Workers Party, Kang Sok-ju, reportedly passed through Beijing twice in five days last week, at the beginning and end of a European tour. Unusually, no Chinese officials greeted him on either visit.