Comfort women clash: Progress on Japan and S. Korea's thorniest dispute?

After three years of frosty relations and no meetings, the two nations' leaders say they will try to end an impasse on a World War II issue that has roiled relations and frustrated Washington, their mutual ally.

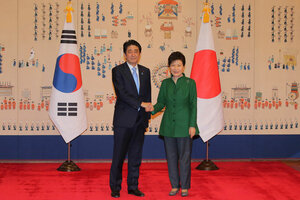

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe shakes hands with South Korean President Park Geun-hye before a bilateral summit in Seoul on Monday.

Lee Jung-hoon/Yonhap via Reuters

Beijing

For years Washington has pressed its two closest allies in East Asia, Japan and South Korea, to get over their differences and pull together in the face a rising China.

On Monday, after meeting for the first time, Japanese Premier Shinzo Abe and South Korean President Park Geun-hye said they will try to settle their thorniest dispute – over “comfort women” forced to work in Japanese military brothels during World War II – “as early as possible.”

The announcement raised hopes that the two leaders may be ready to strike new compromises and that problems that have kept them apart for three years may begin to recede.

“Not many people have high expectations that this issue will be resolved quickly,” says Yu Myung-hwan, a former South Korean foreign minister closely involved in relations with Japan. But he says that “Mr. Abe is a pragmatic politician and I believe he wants to put this behind him.”

A deal with South Korea would help soften Abe’s reputation in the region as a strong nationalist. It could also abate fears about his ambitions for Japan to take a more active military role in regional affairs.

Ms. Park, meanwhile, has signaled that Seoul is ready to decouple the comfort women issue from other items on the bilateral agenda and allow for the closer cooperation that Washington would like to see.

Galling for Koreans

That is a significant concession given how large the comfort women question looms over the Korean peninsula, which Japan occupied for decades prior to WWII. In 2011, the Korean Supreme Court ordered the government to press its case more forcefully with Japan. But the issue became especially galling to Koreans in 2014 when Abe’s government began promoting a revisionist version of colonial history. It implied that Korean women were willing participants in the brothels.

Park has made it a personal crusade to see justice for the Korean comfort women. Only 47 of them remain alive, and they are mostly in their 90s. Until Monday Park had refused to meet Abe until Japan offered them new apologies and compensation.

That Park relented on this condition “indicates that South Korea is showing a more conciliatory posture towards Japan and the Japanese government has taken that opportunity,” says a senior Japanese official familiar with government thinking. “We have chosen to be just a little bit hopeful.”

It is unclear whether Japan too is ready to be conciliatory. Koreans close to the seven rounds of fruitless negotiations that senior foreign ministry officials have held say Tokyo still refuses to take legal responsibility for the “comfort stations” in which Korean and other Asian women were forced to have sex with Japanese soldiers.

Political decision needed

Japanese negotiators, on the other hand, complain that Seoul has refused to offer cast iron assurances that any deal will be the final word on the matter, closing it forever. Tokyo argues that the 1965 treaty restoring diplomatic relations prevented subsequent claims on Japan by Korean citizens.

Such logjams could yield if “both sides make a political decision” at the top, says Mr. Yu.

Park’s ability to make compromises is limited by the organization set up to support former comfort women, the Korean Council of Women, which scuppered an earlier Japanese effort to resolve the issue by branding it insufficient.

Abe, on the other hand, while backing away from suggestions he would revoke an apology for the military brothels by a previous Japanese government, has denied there is any evidence that Japanese troops coerced Korean women into prostitution.

“What happened in the war will be irrelevant to whatever deal that could take place,” says the Japanese official. “It is all a matter of current politics.”

To Koreans, who expect any deal to serve as a Japanese acceptance of responsibility, such an attitude smacks of insincerity. “The ball is in Japan’s court now,” says Park Joon-woo, formerly one of Park’s closest advisers. “We have to wait and see how flexible Abe can be.”