North Korea's nuclear threat: Where do the US and China go from here?

As tensions escalate on the Korean peninsula, China’s patience with the US is growing thin. But US Secretary of State Tillerson left his first official trip to Beijing without concrete steps on North Korea.

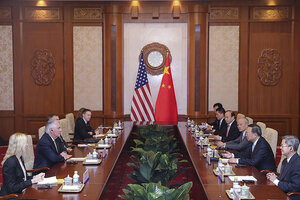

U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson (2nd l.) and Chinese State Councilor Yang Jiechi (2nd r.) attend their meeting at Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing on Saturday.

Lintao Zhang/Pool/AP

Beijing

For the Chinese, their proposal perhaps seemed obvious: North Korea would suspend its nuclear and missile tests in return for the United States and South Korea halting their annual joint military exercises. After the mutual displays of good faith, the two sides could reengage in negotiations.

But the idea was quickly shot down in Washington, and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson rejected it again last week before visiting Beijing. It became yet another wishful attempt at compromise as the two heavyweights struggle to forge a common strategy over North Korea’s expanding nuclear program.

As tensions escalate on the Korean peninsula, China’s patience with the US is growing thin, says Wu Riqiang, a nuclear expert at Renmin University in Beijing. With the North Korean threat growing – Kim Jong-un just tested a new high-thrust missile engine that analysts said could be used in an intercontinental missile – the question now is where the US and China go from here.

Out of patience

Early in his first term, former President Obama touted a new approach of “strategic patience.” Rather than overreact to North Korea's every bomb and missile test, his administration elected to gradually ratchet up sanctions until the isolated countyy agreed to negotiate.

But the policy was more akin to “malign neglect” in the eyes of its critics. By the time Mr. Obama left office earlier this year, experts estimated the North had acquired enough plutonium and highly enriched uranium to build 20 to 25 nuclear weapons. It now appears to be closer than ever to developing a nuclear-tipped ballistic missile capable of hitting the continental US.

Few North Korea observers deny the failure of the strategy. On Friday, Secretary of State Tillerson made clear that the Trump administration would take a tougher approach.

“The policy of strategic patience has ended,” Mr. Tillerson said in Seoul after visiting the heavily militarized border between the North and South Korea. “We are exploring a new range of diplomatic, security, and economic measures. All options are on the table."

All options – including pre-emptive military action – except the mutual freeze proposed by the Chinese, that is. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, who proposed the confidence building measures that the US rejected, urged the US to take a "cool-headed” approach to the North.

‘A different course’

Tillerson arrived in Beijing Saturday to try to narrow the strategic gap. President Trump tweeted Friday that China had “done little to help” on North Korea, a notion the Chinese state-run news agency Xinhua rejected in a commentary the next day.

“Positive results require effort and good faith from both sides,” the commentary said. “China has never fallen short of offering its fair share. It's all up to Washington now.”

Tillerson and his hosts managed to strike a cooperative tone, at least publicly, during his 24-hour visit, with Tillerson saying the two sides would work together to get North Korea to take “a different course.” And on Sunday, he said the US looked forward to stronger ties with China in his meeting with President Xi Jinping, who responded that “the China-US relationship can only be defined by cooperation and friendship.”

But such cooperation needs careful shaping, says Yang Xiyu, a senior fellow at the China Institute of International Studies.

“The most important thing for the meeting was eliminating the uncertainty in the relationship between China and the US,” he says. “For the next step, if the ‘double suspension’ doesn’t work, China will need to think about new ideas.”

For now, Tillerson said Washington would focus on tightening UN sanctions against North Korea before pursuing military options. Analysts say he likely pressed Chinese leaders to more fully implement them or risk an expansion of the US air defense system in East Asia, known as THAAD, a move China strongly opposes.

Beijing says it’s committed to enforcing economic sanctions. Last month it abruptly halted imports of coal from the North, ending one of Pyongyang's main sources of foreign currency. Still, a recent study by the Institute for Science and International Security, a Washington-based research organization, found that China has allowed materials used to make hydrogen bombs to cross the border. Beijing has long been wary of pushing Pyongyang too hard for fear of sparking a regime collapse and refugee crisis.

Zhao Hai, a research fellow at the National Strategy Institute at Tsinghua University, says that he wasn’t surprised Tillerson left Beijing without concrete steps on North Korea. He says the real test will come next month when Xi and Trump meet in the US.

“The US is still undergoing a review of its North Korean policy and China is also undergoing a domestic debate,” Professor Zhao says. “Both sides need to clarify their common goals so they can come up with common solutions.”

• Xie Yujuan contributed reporting.