How the Cultural Revolution shapes Chinese families decades later

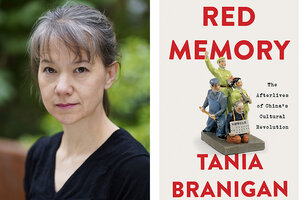

Tania Branigan is the author of "Red Memory: The Afterlives of China's Cultural Revolution."

Dan Chung/Norton

In “Red Memory: The Afterlives of China’s Cultural Revolution,” British journalist Tania Branigan reveals the profound yet often hidden present-day reverberations of the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution. During the fanatical campaign unleashed by Mao Zedong, Red Guards persecuted and killed millions of people across China. Betrayal and mistrust divided students and teachers, neighbors, and even families.

Then, in a jarring shift, China’s post-Mao leaders denounced the Cultural Revolution as a “catastrophe” as they redirected the country’s energies away from the pursuit of a communist Utopia and toward market-oriented economic growth. Ordinary Chinese people were allowed to speak about the ordeal, for a time. But Beijing, eager to control the historical narrative and mute criticism of Mr. Mao, gradually began to suppress all but brief mentions of the disastrous campaign.

Enter Ms. Branigan, who began meeting with individuals and capturing their stories while covering China for The Guardian from 2008 to 2015.

Why We Wrote This

In her book “Red Memory,” journalist Tania Branigan offers a candid look at China’s Cultural Revolution and illuminates the relevance of that decade of chaos in deciphering China today.

You studied politics and sociology, and were drawn to reporting as a teenager. What led you to become a China correspondent?

China is the story of our time, and it seemed to me an unmissable one. I was working as a national reporter at The Guardian, and I kept badgering my editors saying I wanted to go to China. In 2008, the Olympics year, they agreed to send me out, and I stayed for seven years. I was incredibly privileged to be there then. It was a transition time from a point where there still seemed to be a real sense of possibility, with a lively civil society, and then from 2011, ultimately a turn toward a much more repressive and closed environment.

You write that it is impossible to make sense of China today without understanding the Cultural Revolution. What are the key insights from that tumultuous decade?

The most obvious impact is in the field of politics. The message from the Communist Party to ordinary Chinese is: “Accept party rule, because if you don’t, there will be chaos and turmoil, and we’ve seen how bad it can get if we’re not running things and we don’t have a firm hand.”

In very personal terms, family relationships have been deeply shaped by the Cultural Revolution, whether it’s people who never really got to know their parents because they were sent away to labor camps ... or parents so traumatized by their experiences that they are teaching their children that it’s impossible to trust anyone.

How have memories resurfaced recently, such as during the pandemic?

People drew parallels with the very draconian “zero-COVID” policies and the experience of people barging into your house and dragging you out. We’ve also seen it on the streets, when there was a protest against “zero-COVID” and you saw people with a sign saying, “We want reform, not the Cultural Revolution.”

Why is China’s current leadership so determined to suppress public commentary about that formative period in the country’s recent past? You describe a kind of collective “amnesia” that authorities are working hard to maintain.

They don’t like talk about anything that reflects badly on the Communist Party. And while they have not walked away from the official verdict that it was a catastrophe, they don’t want people to dwell on it. They want to unite people and move on. ... If you criticize Mao himself, then you’re really attacking the very roots of communist rule. Finally, if you acknowledge that people have a right to criticize former leaders, why shouldn’t they be criticizing current leaders? It’s just not a precedent that the party wants to set. They don’t want to grant people that space. If people can judge history, they can judge the present as well.

Yet, as you note, memories are persistent. When painful memories are not allowed to be aired or recognized by society, what happens to the psychological trauma?

It takes an immense toll. ... We see this transgenerational trauma, when you see the trauma handed down and experienced through the generations. It plays out in these family relationships and in the way people view the world.

I talk about a young student at university who seemed tremendously well behaved and obedient. Suddenly, he posted this very graphic account ... of attacking and killing one of his lecturers. When he’s eventually seen by a mental health professional, and his parents come in to discuss it, it suddenly emerges that his grandfather was murdered by Red Guards in front of his father, and his father over all these years has never spoken a word of this to his son. He was trying to protect his son. But he had brought up his son with this sense that strong emotions are something that have to be repressed at all costs. You could not show any anger, any frustration.

Tell me about the person you met while writing this book who stays with you the most.

They all stay with me in one way or another. ... I think of Wang Xilin, the composer who almost died in the Cultural Revolution. He ... said, “If somebody calls my name out on the street, my blood runs cold.” That took him back to the struggle sessions [public rallies where so-called class enemies were accused and attacked] and waiting for the moment that somebody would call his name and he would be beaten. All these decades later, he retained that sense of vigilance, that sense of living with perpetual uncertainty. Yet in spite or because of his experiences, he has such an extraordinary thirst and passion for life. People have not only survived but even managed to thrive. They have gone on to live their lives, and in the case of Wang Xilin, really to embrace life. The Cultural Revolution shows how terrible human beings can be, but humans are also remarkable.

What lessons can we learn from your book about dealing with collective memories?

It wasn’t a book just about Chinese people but about all people. It’s a really important reminder to us, that we have to be honest about our pasts.