Dalai Lama must balance politics, spiritual role

The Tibetan leader in exile must balance his stature as a monk with the very temporal demands of politics.

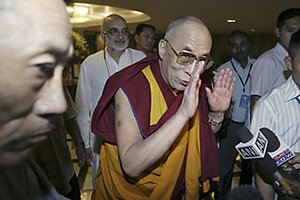

Dalai Lama: He has no political power, but holds a global moral authority.

Mustafa Quraishi/AP

New Delhi and Beijing

Thrust inescapably into the eye of the international storm currently raging over Tibet, the Dalai Lama enjoys unique status as both the spiritual and political leader of Tibetans worldwide. That status, however, also poses him unique challenges.

As the symbol of Tibetan aspirations for greater freedom from Chinese rule, the Nobel Peace Prize winner is buffeted from one side by Chinese officials vilifying him and from the other by young Tibetan exiles urging him to be more strident.

He must balance the concerns of a wary Indian government – which hosts his government in exile – and the desperation that Tibetans in China have expressed through their recent unrest.

Beyond all that, he must, as a Buddhist monk, match his words and actions in the worldly political arena with the nonviolent philosophy at the heart of his spiritual practice.

"What the Dalai Lama is currently doing is walking a tightrope," says Srikanth Kondapalli, a Tibet expert at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.

That balancing act, adds John Bellezza, a Tibet scholar who knows the Dalai Lama, is made all the harder because "his temporal and spiritual leadership don't always harmonize as well as they might. Many of his difficulties are due to the underlying tensions he feels between the two hats that he wears."

No conventional political power

The Dalai Lama, who fully assumed his office 57 years ago, has scarcely any conventional political power: he controls no territory and heads an exiled government that no state recognizes.

Instead, he has parlayed a global moral authority matched only by Nelson Mandela into a commanding influence over world public opinion that sometimes has political consequences.

United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon last week exhorted Beijing to show restraint in dealing with Tibetan unrest, for example, and the speaker of the US House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, visited the Dalai Lama at his Indian headquarters in Dharamsala on Friday to urge the world to "speak out against China." China responded harshly, accusing Mrs. Pelosi, a longtime critic of China, of disregarding the rioters' actions.

The Tibetan leader's insistence on his readiness to talk with the Chinese government and his nonviolent approach "play very well internationally," says Brahma Chellaney, a China analyst at the Centre for Policy Research, a New Delhi think tank. "He has presented himself as a moderate, [even though] all he gets is oppression."

That has kept the Tibetan cause in the public eye in the West. But in his homeland, his 20-year-old policy of nonviolent pursuit of limited autonomy under Chinese sovereignty has proved fruitless.

Tibetans in the Tibetan Autonomous Region, as Beijing calls the area, are generally more prosperous than they were two decades ago,. But they enjoy no greater religious freedom, they complain that an influx of Han and Muslim Hui Chinese migrants has diluted their culture, and there are no signs that the government in Beijing is ready to relax its grip.

"He is the first to acknowledge that, so far, there have been no tangible results from his policy of patience," says Pico Iyer, author of "The Open Road," a portrait of the Dalai Lama to be published this week, who has talked at length with the Dalai Lama over many years.

"Twenty years of patience have just seen more and more terrible things," he adds.

Some say the Dalai Lama has had no choice, and that his policy of garnering support from Hollywood stars and ordinary citizens abroad has been worthwhile. "The high international profile of Tibet that the Dalai Lama has created has gone some way to protect Tibetans," argues Kate Saunders, spokeswoman for the Washington-based "International Campaign for Tibet."

"If the Dalai Lama had changed his policy, would that have made any difference to what China is doing?" she wonders.

Other experts suggest that the Dalai Lama and his advisers have missed opportunities in the past, such as when they turned down an invitation to visit China by then-Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping.

And, says Tibet scholar Ian Baker, the exiled government showed "a lack of political savvy and diplomacy" when its delegation to six rounds of intermittent talks with Beijing since 2002 included no fluent speaker of Mandarin Chinese.

At the same time, Mr. Bellezza points out, the Dalai Lama "has bent over backwards to take a nonviolent approach and to accept Chinese sovereignty over Tibet" – positions that he has reiterated countless times over the past 20 years, but which Beijing – branding him a supporter of independence – continues to insist it does not believe.

The Dalai Lama's "temporal role is entirely guided and lit up by his philosophy," says Mr. Iyer, and the results have led some observers to question if his Buddhist vision of the world is always in line with the demands of mundane politics.

"Historically," says Mr. Baker, "Tibetans have been bad at being politicians and much better at being monks. It is one of their great misfortunes that their advances in the study of consciousness and spirituality have not been balanced on the secular and political side."

"Monks think in terms of centuries, many more generations than the rest of us," Iyer points out. "The Dalai Lama believes that acts generated by impatience do not generally bring good results. And at the core of his belief, everyone is interconnected: There is no sense in resisting China [through calls for independence] because Tibetans and Chinese are all part of the same whole."

Outlook frustrates younger exiles

Such metaphysics frustrate younger Tibetan leaders in exile, who have grown increasingly vociferous in their skepticism of their leader's commitment to non-violence and limited autonomy for their homeland, rather than the full independence they dream of.

Their urge for defiance, says Iyer, is an example of conventional politics that "the Dalai Lama is trying to transform. Normal politicians debate whether a car should be painted red or blue: the Dalai Lama wants to rewire the engine."

That approach to politics is hard to grasp not only for the political leadership in Beijing, but also for ordinary Tibetans. Their overwhelming respect and veneration for the Dalai Lama appears undented, but in Lhasa and other Tibetan towns in China, they are worried about such immediate issues as their job prospects and fears that the authorities treat them as suspect second-class citizens.

Such resentments fueled the sort of protests Tibetans staged around southwestern China, says Jabin Jacob, a China-watcher at the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies in New Delhi. "This is turning into a conventional independence movement with many leaders, and there might be violence," he warns.

For now, however, the Dalai Lama "is the only unifying force" capable of delivering any kind of agreement with Beijing, says Baker. "If he disappears," he says, "all the pent-up frustrations will arise in ways that no one will have the moral authority to control any longer."