Pakistan: Do school texts fuel bias?

The curriculum, critics charge, promotes revisionist views and intolerance. Others say they don't see such imbalance.

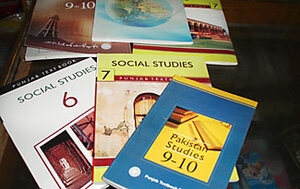

Point of View: These 2008 texts, used in Pakistan's Punjab Province but approved nationally, omit references to minority festivals and contain anti-Indian references.

Issam Ahmed

Lahore, Pakistan

As Pakistani Air Force jets circled the eastern border city of Lahore last week in a show of strength, journalist Rab Nawaz was despondent. But what occupied him was less the threat of war with India than the things his son had begun saying recently.

"My 7-year-old came home from school one day insisting that Indians are our natural-born enemies, that Muslims are good, and Hindus are evil," the widely traveled journalist recalls. "He asked about the relative strength of our air forces and insisted we would win if it came to war.

"It was only when I asked him whether my Indian friends ... were also bad," he adds, "that he began to realize that things weren't quite so simple."

Public schools, though long neglected, are still responsible for educating the vast majority of schoolchildren. Some 57 percent of boys and 44 percent of girls enroll in primary school, and about 46 percent of boys and 32 percent of girls reach high school.

All public schools must follow the government curriculum – one that critics say is inadequate at best, harmful at worst.

According to Pervez Hoodbhoy, a physics professor at Quaid-e-Azam University in Islamabad, the "Islamizing" of Pakistan's schools began in 1976 under the rule of the former dictator, the general Zia ul-Haq.

An act of parliament that year required all government and private schools (except those teaching the British O-levels from Grade 9) to follow a curriculum that includes learning outcomes for the federally approved Grade 5 social studies class such as: "Acknowledge and identify forces that may be working against Pakistan," "Make speeches on Jihad," "Collect pictures of policemen, soldiers, and national guards," and "India's evil designs against Pakistan."

"It sounds like the blueprint for a religious fascist state," says Professor Hoodbhoy. "You have a country where generations have grown up believing they are surrounded on all sides by enemies, they are the only righteous ones, and the world is out to get them."

It is this siege mentality that led to some of the head-in-the-sand reactions by the Pakistani media and public in the aftermath of Mumbai, he suggests.

"There was a flat denial that it could be Pakistanis," he says. "Anyone suggesting the contrary was labeled an enemy of the state or unpatriotic. When I said on television there are groups in this country dedicated to harming India – the furor ... was quite astonishing."

Amanullah Kariapper, a young software engineer and cofounder of Young Professionals of Lahore, an informal alliance dedicated to human rights causes, agrees.

Mr. Kariapper says he began revising his world views when he went to college, first at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) and later in Grenoble, France. The process came full circle when he was briefly arrested in November 2007 for protesting former President Pervez Musharraf's declaration of emergency and suspension of civil rights.

General Zia's curriculum was inherited by the successive governments of Benazir Bhutto, Nawaz Sharif, General Musharraf, and now, Asif Ali Zardari.

An Islamist alphabet chart published in this month's Newsline shows Urdu letters accompanied by guns, daggers, and a depiction of planes crashing into the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001. The chart is not approved by the government. But it is, the article claims, in use by "by some regular schools as well as madrassahs associated with the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, an Islamic political party that had allied itself with General Musharraf." The Ministry of Education says there are 1.5 million students in 13,000 madrassahs acquiring a parallel religious education.

Critics also complain about insensitivity toward minorities. A section on Christian festivities in the Federal Ethics textbooks had been removed, according to a Daily Times report from 2006 titled "O Jesus, where art thou?" Hindu and Sikh festivals were mentioned only fleetingly.

In the latest edition of Pakistan Studies for Grades 9-10, approved by the Punjab textbook board, all mention of non-Muslim festivals of Pakistan had been removed. Hindus and Christians make up about 5 percent of the population of more than 170 million.

In 2007, two Pakistani students at Middlebury College, Hamza Usmani and Shujaat Ali Khan, embarked on a review of all state-sanctioned texts in a project called "Enlightened Pakistan."

They enlisted contacts ranging from seniors in high school to teachers. The bulk of their report (www.enlightenedpakistan.org), targets poor teaching in sciences, languages, and math. But in social sciences and history, they found "disturbing" themes like "Pakistan is for Muslims alone," "The world is collectively scheming against Pakistan and Islam," and "Muslims are urged to fight Jihad against the infidels."

The report notes that the textbooks routinely engage in historical revisionism and place questions designed to portray Hinduism as an inherently iniquitous religion: "There is no place for equality in Hinduism. Right/Wrong."

Mr. Usmani says the texts encourage illiberal worldviews and "dumb down" education. "No opposing views are presented, no differing ideas. It makes the population less intelligent," he says.

But Rasul Baksh Rais, a professor at LUMS, argues that every nation has the right to construct its own historical narrative as part of the legitimate process of nation-building. "Perhaps they [the critics] simply don't want us to be on that track at all or they want us be a very confused nation. It's a negative attitude toward Pakistan," he says, adding he has yet to see proof of anti-India or anti-Hindu bias.

"The roots of Pakistani resentment toward India lie in causes such as the conflict in Kashmir and the ongoing oppression of Muslims," says Mr. Rais.

Mr. Usmani says it's a case of how far one goes. "All nations need to support their national fabric. But you have to draw the line somewhere. Nazi Germany, Stalinist Russia – these are not examples you want to emulate. This debate is about where to draw that line."

Amir Raza Malik, a Ministry of Education spokesman, declined to comment on previous curriculums, but said the Ministry was preparing an overhaul that would be unveiled in 2010. "If there is any objectionable material, it would certainly be removed," he says.