Why Pakistan's old jihadis pose new threat – at home and in Afghanistan

In an interview, a jihadi talks about why state-sponsored militants who once fought in Indian-controlled Kashmir are now joining the Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

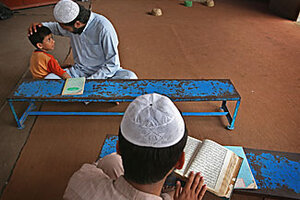

Madrasa lessons: A child learns from an older student at a religious school in Lahore, Pakistan. Some of the schools have become breeding grounds for jihadis.

Newscom/File

hafizabad and lahore, pakistan

Saeen Dilawar hadn't killed an infidel in years.

Like many of his friends from Pakistan's Punjab Province, in the 1990s he rushed east to help the Army fight the Indians in Kashmir. When government support dried up in 2002, he returned home to his quiet farming town of Hafizabad.

But last summer, Mr. Dilawar found a new cause. This time he headed west to join the Taliban, sneaking across the mountainous border to Afghanistan to fight NATO forces.

"Unfortunately, I have not yet killed an American," he says. Shrapnel from enemy shelling broke his left leg and sent him hobbling home, he says.

In recent years, Pakistan has aimed its antiterror offensives at the Taliban network operating in the remote northwestern tribal districts, a largely ethnic Pashtun movement in an area that has long resisted state rule.

But another militant threat is rearing its head in Punjab, Pakistan's most populous province and its heartland; home to the country's capital, cultural hub, and military headquarters. Once-dormant Punjabi jihadists like Dilawar are beginning to link up with the Taliban, supplying manpower in battles in the northwest but also bringing the fight to Pakistan's center by carrying out attacks on their home turf.

Some 5,000 former Punjabi fighters have returned to combat as part of what is being called the "Punjabi Taliban," according to Hassan Abbas, a fellow at the Asia Society in New York. More young men could join, spurred by radical madrasas, or religious schools, that dot the province, advocating jihad.

Pakistan's government has shown reluctance to crack down on these militants, many of whom were trained by the state to fight proxy wars in Kashmir and Afghanistan. But militants are not showing the same restraint for their onetime backers, as evidenced by a slew of attacks in Pakistan this year.

The latest occurred on Dec. 8, when an explosive laden-truck blew up outside a police check-post, killing 12 people. A day earlier, twin strikes in a crowded Lahore market place killed more than 40 people, mostly women and children, and last Friday a coordinated attack in a Rawalpindi mosque also accounted for more than 40 lives, prompting President Asif Ali Zardari to make a rare public appearance at the hospital where the injured are being treated.

Attack on Pakistan's 'Pentagon'

In October, the so-called Punjabi Taliban claimed credit for a 22-hour hostage raid on the Army headquarters in Rawalpindi that left 23 dead. A few days later, a triple strike on an intelligence agency headquarters and two police academies in Lahore brought life to a standstill in the country's once-peaceful cultural hub.

"These militants were backed by both Pakistan and the United States in the past. When they are left alone, some of them do go rogue," concedes a senior Pakistani intelligence chief who asked to remain anonymous.

Sitting among friends at his neighborhood mosque in Hafizabad after early evening prayers, Dilawar recalls his early days as a jihadist.

Fed a diet of jihadi fiction about injustice against the Palestinians, he decided in 1992 to join Hizb-ul-Mujahideen, the militant wing of a mainstream religious party, Jamaat-e-Islami, which was sponsored and trained by Pakistan's intelligence agency. His career, he says, began under the command of infamous Islamist warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, a man now desperately sought by the US for his attacks in Afghanistan.

Dilawar participated in four sorties into Indian-administered Kashmir before he was forced into "retirement" because the government dropped its support for Hizb-ul-Mujahideen. He returned home, married, and began to farm.

But "a true jihadi never retires," he is quick to emphasize. Dilawar recalls with satisfaction how he abandoned his field and returned to the front – this time in Afghanistan. "There is no feeling quite like killing kaffirs [infidels]," he says, pointing proudly at the deep scar from a shrapnel injury.

Dilawar's friend Akbar Ali Alvi, a former Jamaat-e-Islami official, adds: "The war may be in Waziristan [a tribal district] and Afghanistan now, but, God willing, we will bring it to the streets of New York and Washington."

Once sponsored by US, Pakistan

Many Punjabi militant groups, which like Hizb-ul-Mujahideen were founded in the 1980s and '90s, profess similarly expansive goals. Others are dedicated to violence against Shiites or to battling Indian forces in Kashmir. Some fought with the mujahideen in Afghanistan against Soviet forces, (1979-89) with support from the Pakistani and US governments.

Principal among these groups are Sipah-e-Sahaba, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, and Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM), based in the south of the province, and Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), in the center.

After the US invaded Afghanistan in 2001, and Pakistan's then-leader Gen. Pervez Musharraf pledged support for its "war on terror," the Pakistani government was forced to ban some of these militant groups and scale back its dealings with them, especially with JeM and LeT, which had been used to conduct covert proxy wars with India.

But many groups continued to operate openly, and some established ties with the Taliban and Al Qaeda. On Nov. 25, Pakistan indicted seven alleged LeT members for involvement in the November 2008 terror attacks in Mumbai (Bombay).

The US has repeatedly expressed concern about these groups and about the Pakistani government's failure to rein them in. A recently passed US aid program, the Kerry-Lugar bill, provides $7.5 billion in civilian aid over five years – but it attached conditions that Islamabad crack down specifically on JeM and LeT.

The Pakistani government may hesitate to target these groups because it might be able to use them again someday as proxy fighters against India or Afghanistan, and because it wants to avoid becoming their next target.

"You sometimes have to tolerate the little things," says the Pakistani intelligence chief. "We don't want to create a new Lal Masjid," a reference to the violent backlash that resulted when the Army stormed the extremist Lal Masjid (Red Mosque) in Islamabad two years ago.

Publicly, the Punjabi government has sought to play down the threat of a "Punjabi Taliban." The province's law minister, Rana Sanaullah, insists that organized terror does not exist in Punjab.

Privately, however, some officials admit deep concern. Jehanzeb Burki, a key adviser on law and order to Shahbaz Sharif, the chief minister of Punjab, says the government is taking the threat very seriously "because they are targeting us."

Asked whether the government may be giving a free pass to militants from Punjab who operate outside the country, he says: "As far as the government of Punjab is concerned, our first priority is to deal with those groups focused on Punjab itself."

Are madrasas breeding grounds?

Though much of the discussion on Punjabi militancy has focused on the poorer, less-developed southern part of the province, evidence shows that militants are being drawn from other parts as well.

The masterminds behind the Army headquarters attacks in October came from Rawalpindi and Faislabad, in the north of the province, says Ashar Rehman, Punjab bureau chief of Dawn, a leading English daily.

Suspects in other high-profile attacks – such as Ajmal Kasab, the lone surviving Pakistani gunman of the Mumbai attacks – also came from Punjabi areas outside the south.

Some of the madrasas spread across the region are fueling hard-line views. Punjab is home to more than 6,000 of the country's 8,000 madrasas. With the help of funding – mainly from Saudi Arabia – they have grown exponentially since Pakistan's independence in 1947, when the number of madrasas nationwide was 137.

Only a handful of the schools are worrisome, and "not all students in these madrasas will become fighters," says Mr. Burki, the government adviser. "But some problematic teachers will keep an eye out for the raw minds they feel they can work upon, perhaps two or three from each batch."

At the Jamia Muhamaddia madrasa in Lahore, a school for 400 students, young men undergo vigorous religious training in the Ahl-e-Hadith doctrine, an orthodox strain of Islam imported from Saudi Arabia.

The school's principals, Khawar Rasheed and Hafiz Ata-ur-Rehman, deny that their institution preaches war against America or intolerance for other sects.

These claims seem to be contradicted by the school's monthly magazine, Sawt-ul-Haq ("Voice of Truth"), which, on the subject of jihad, notes: "God shows his wrath for those who shy from Jihad. Jihad is one of the reasons God is kind to Muslims. They who deserve His mercy are they who engage in Jihad."

Jihad can also refer to the internal struggle Muslims must undergo to improve themselves morally.

But in the brochure, jihad seems to mean violence: "In this day and age, Jihad has been incorrectly labeled terrorism and militancy. Our rulers are trying to please the non-Muslims … on America's command."

Outside the madrasa, Asif, a teenager who joined the madrasa at age 11, contemplates his future. He wants to complete the remaining seven years of his religious education.

Then, he says, "I will do the work of Islam, by fighting Islam's enemies in Afghanistan and Kashmir."

Also: