Pakistan's Islamic preachers: Gateway to radicalization?

Since 9/11, Pakistan's Islamic preachers have gotten far less international scrutiny than in militant groups. But the social and religious conservatism they preach could be an even more radicalizing force.

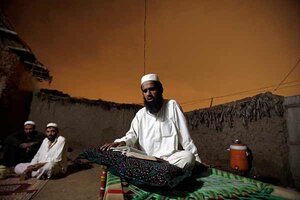

A Pakistani man (c.) reads verses of the Quran, during Laylat al-Qadr, the 27th day of the holy fasting month of Ramadan in a Mosque in a slum on the outskirts of Islamabad, Pakistan, Aug. 27. Since 9/11, Pakistan's Islamic preachers have gotten far less international scrutiny than in militant groups.

Muhammed Muheisen/AP

Karachi, Pakistan

Hawkers park their carts next to the latest-model cars of business tycoons as thousands of men rush into the Madni Mosque in Karachi city.

Inside, the atmosphere is electrifying: prayers, redemption, and celebrity sightings, as commoners get transformed into global Islamic preachers – all in the name of “Muslim victories.”

A crowd of some 40,000 worshipers is instructed by the mosque’s cleric to “spread the message among Muslims in every street, in every city.”

This is the weekly congregation of Tablighi Jamaat.

The religious movement of proselytizers is an offshoot of the Deobandi sect, which takes a literal approach to Islam.

The use of the hijab (veil), the act of growing beards, and the wearing of ankle-length trousers – all symbols of conservative Islam – are increasingly the norm here. Boutiques have mushroomed for fashionable veils, and Islamic-only bookshops are flourishing in posh neighborhoods.

All of this would be fine, say analysts, but Pakistanis who choose not to follow such strict requirements feel suffocated, and many believe that the trend of converting more and more Islamic preachers will only further push society into radicalism – and ultimately lead to more silent support of militant groups.

Since 9/11, Pakistan’s militant groups have been under scrutiny internationally. But it’s the accelerating social and religious conservatism that is more socially corrosive, providing the gateway to radicalization, say some observers.

“Especially after 9/11, there is increasing extremism in terrorism-hit Pakistan. These preachers, by radicalizing various layers of the society, will ignite it – so these groups and their activities should be put under the counterterrorism [microscope] rather than ignoring them as nonpolitical and nonmilitant preachers,” says Arif Jamal, author of “Shadow War: The Untold Story of Jihad in Kashmir.”

All ages participate – men with long beards or short beards, caps or turbans, shoulder bags or backpacks. Teenage boys, eyes wide, listen to the narrations of experienced preachers of their mission travels to America, England, and Africa.

In July, Federal Interior Minister Rehman Malik reportedly called the missionary center of Raiwand, the headquarters of Tablighi Jamaat near Lahore, the “breeding ground of extremism” and terrorism in Pakistan, and said it had a major role in brainwashing Pakistanis. According to police reports, he said, many terrorists under arrest in Pakistan had attended the congregations with Tablighi Jamaat.

The statement triggered sharp criticism from top politicians, including former caretaker Prime Minister Chaudhary Shujat and current Chief Minister of Punjab Province Shahbaz Sharif.

Mr. Malik later played down his statement by saying it was distorted, but many analysts say it rang true.

“The continuous indoctrination of [the] orthodox version of religion at the Tablighi missions [events] turns a large number of people into Islamists and jihadists. Even when they do not take part in violent jihad, its loose organizational structure helps militants conceal their identity, and they provide it popular support,” says Mr. Jamal.

Tablighis shrug off these allegations as conspiracies. “We are nonpolitical and only focus on spreading the message of Islam, which is of peace and love across the world,” says Syed Imran, an imam and member of the Tablighi Jamaat religious movement for almost a decade. “Not on a single occasion has any local or international investigating agency found the faintest of evidence of militancy in our movement,” he says.

“[The] jihadis challenge us for not waging war and call us passive Islamists. We tell them ‘we are engaged in greater jihad by purifying Muslims and bring them on the right path,’ ” agrees Mohammad Javed, who is actively involved in missions.

While Tablighis belong to the Deobandi sect, another group, the Dawat-e-Islami of Barelvi, has a similar proselytizing campaign in Karachi, where their international headquarters are situated. Known as Faizan-e-Madina, the sprawling headquarters has followers across Norway, Australia, America, Canada, and England. It also has centers in Texas, Chicago, and California. Followers usually wear a green turban, as green is associated with the prophet Muhammad.

Then there is Hizb ut-Tahrir (Liberation Party), another nonmilitant but highly political organization. It is working for the reestablishment of a caliphate, or Islamic state in the Muslim world, and is dismissive of the idea of democracy.

Contributing to the radicalization of Pakistan?

Many analysts believe that these groups are not perceived as a serious threat because they are not armed; yet the views of all three of these groups are contributing to the radicalization of Pakistanis across all classes, they say.

“[The groups] insist that people’s only valid identity is their religion, and they thrive on a narrative that Muslims all over the world are the victims of conspiracies,” says Nadeem Farooq Paracha, a cultural critic and columnist for the leading English-language newspaper Dawn. “They are shrinking secular spaces in the public sphere.”

“While they seem nonpolitical, what they propagate ultimately provides ideological ground to militant outfits. Because they are not armed does not mean they are tolerant of other views,” adds leading rights activist Farzana Bari.

Early this year, progressive groups campaigned to abolish the controversial blasphemy law, which bans “insulting the prophet”: Islamists, including green-turbaned preachers castigated them as “infidels.” It was amid that charged atmosphere that Gov. Punjab Salman Taseer was killed by his own guard because he supported its abolition.

In 2006, after a stampede in the women’s congregation of Dawat-e-Islami left several severely injured, followers did not let male medical workers help injured women because it they considered it “un-Islamic for strangers to touch women.” Several women died because of the delay in providing medical assistance. “It has trickle down effect. These men use private patriarchy for compliance of their female family members and children so the radicalization process multiplies. They are pushing for more religious and conservative society by shoving them in centuries-old Arab world,” says Ms. Bari.

While Taliban militants use guns and bombs, the preachers use nonviolent tactics, such as securing support of world-class cricket players and pop stars, which columnist Mr. Paracha terms as “poster boys” for attracting millions of youths who idealize them.

Popular appeal

Famous former Pakistani cricket captains like Yousuf Youhana, now named Mohammad Yousuf newly converted to Islam, now preaches and travels for missions. Saeed Anwer and Inzimam-ul Haq now run Halal meat businesses. Pakistan cricket sensation Shahid Afridi, has joined Tableeghi Jamaat. All of them visit colleges and universities to preach. Their videos carrying message of Islam on YouTube attract hundreds of thousands of hits.

Junaid Shikeh, once a pop-singer now looks after Jawat-i-Islami’s TV channel. The former business graduate is now pursuing eight-year studies to become a chief cleric. “My life has changed completely,” says Sheikh. “I used to sing Summer of ‘69, my ideal was Bryan Adams. Now I have thrown the guitar in a store room and soon there will be a breaking ceremony of it,” he stated matter-of-factly.

“Their tentacles are spreading among politicians, bureaucrats, law enforcement agencies. From poor to filthy rich, their claim of being peaceful helps them attract [the] Muslim Diaspora especially those who live in kind of a social guilt of living in western society,” argues Mr. Paracha.

“They are creating a new urban culture. Since General Zia’s rule of the 80s and the first Afghan war, our traditional tolerant culture has been assaulted by all sides, whereas the best way to defeat extremism is to promote culture and education in our society, says Ahmed Shah, who heads the National Arts Council in Karachi. “The battle is going on between the radicals and us. It is a battle over who gets to define Pakistan.”