Pakistanis hopeful as Nawaz Sharif makes a political comeback

Center-right politician Nawaz Sharif appeared set to return as Pakistan's prime minister on Monday, his third time in the job.

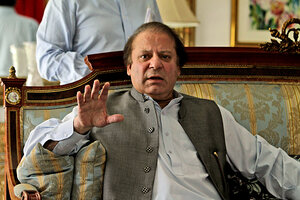

Former prime minister and leader of Pakistan Muslim League party, Nawaz Sharif, gestures while speaking to members of the media at his residence in Lahore, Pakistan, Monday.

K.M. Chaudary/AP

Islamabad, Pakistan

While votes are still being counted after a historic election that should lead to the country’s first civilian-to-civilian government handover, unofficial results show that Nawaz Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League has a massive lead.

Though there have been reports of protests over seats in Sindh and Punjab provinces regarding allegations of election-rigging, analysts do not expect them to affect the results much. And the mood around Islamabad is hopeful, with the election widely seen as a vote of confidence in democracy.

“[Sharif] is religious himself. He knows how to deal with the Taliban. And he knows how to talk to foreign powers. He is the right person for the job because he can take the country forward more united than before,” says Mian Masood, a shopkeeper in Islamabad. Mr. Masood was among the majority of Pakistanis who voted for Mr. Sharif’s party, and represents many who say they are hopeful that Sharif and his party can not only help solve Pakistan’s terrorism problems, but can steer the country out of the current economic and energy crisis.

Election officials say the voter turnout was around 60 percent – significantly higher than the 44 percent of voters who cast a ballot in the 2008 election. Mr. Sharif campaigned on the popular issues of bolstering the economy, ending the energy crisis, and tackling unemployment.

Sharif is not a newcomer to politics: The business magnate was elected prime minister twice in the ‘90s and brings with him a history with both the military and religious militants, which some say may position him well to handled Pakistan's problems.

(Read more about Sharif’s experience with the military, nuclear testing, and militants here)

His party has ruled the most populous province in Pakistan, Punjab, for the past five years, and he reportedly allied himself with political branches of militant groups like Lashkar-e-Jhagvi to attract some of the considerable vote bank they hold in the southern parts of the province. However, although the right-wing conservative pursued a pro-Afghan Taliban policy during his previous stints as head of the country, he has recently said he supported noninterference in Afghanistan and closer ties with India, long considered an arch-enemy.

Indeed, analysts say it appears as though he is slowly trying to distance himself from militants.

“These militant groups are tied to the military, too, so Nawaz has to maneuver the issue skillfully. For example, he gave tickets to a few candidates in those areas known to stand up to the Jhangvi group, and they have won, which shows he is slowly moving in the direction of cracking down against them,” says Ayesha Siddiqa, author of “Military Inc,” a book exposing Pakistani Army’s empire.

Sharif’s nonreligious party, which has a bit of a right-wing flavor, speaks to Pakistan's population, says Ms. Siddiqa. That mix could work well to delegitimize militancy in Pakistan. He also comes with a plan on what to do with the military, which is a good sign, she says; “Pakistan’s existential issue is the civil-military balance and everything boils down to that. If one can control the Army, many issues can be resolved,” she adds, echoing public sentiment.

Though the mood is hopeful here, some Pakistanis are waiting to see results.

“Nawaz Sharif did not perform well twice before,” says Raja Zameer, who drives a taxi in Bara Kahu, a rural village outside Islamabad. “I have no gas for my taxi, and at home we have no gas or electricity most of the time, so I really hope Sharif delivers on these fronts.”