In this Kashmiri library, the power of books goes beyond words

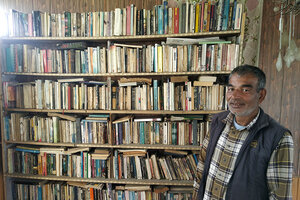

Muhammad Latief Oata stands in front of some of his books, above his shop near Dal Lake in Srinagar, Kashmir, India.

Safina Nabi

Srinagar, India

On a sunny, cold February afternoon, I make my way along narrow lanes and over a bridge to the shores of Dal Lake, one of the most picturesque in Kashmir, with 360-degree views of the Himalayas. The sun-dazzled waters attract photographers, filmmakers, and visitors from all over the world. Houseboats for tourists form rows on the banks of the lake.

Nestled far down the shoreline is a double-story wooden house, home to a library founded by Muhammad Latief Oata, who can hardly read or write.

As we open the compound’s tall gate, Mr. Oata’s wife Zainab greets me. Originally from Chennai, nearly 2,000 miles to the south, she welcomes me in halting Kashmiri: “Salam-u-alaikum, walew b asewtuhepyaraan (Hello, I was waiting especially for you).”

Why We Wrote This

The power of books goes beyond words. Their stories have transported one unique librarian from Kashmir to all over the world.

After climbing a stiff wooden stair, we reach the “Traveler’s Library,” its walls painted white and windows open on three sides. The front overlooks Dal Lake’s houseboats and other boats for everyday use. Next to an old green sofa is a woven wicker table. And on the right are Mr. Oata’s books.

With about 600 volumes, this library may not look like much. But for years, this room has been a place where Kashmir – a beautiful but long fought-over Muslim-majority region, tucked at the top of India – has touched the wider world. It’s been an oasis for visitors, and readers; but most of all, for one book-lover who can’t read.

“Ask as many questions as you can to get the information you require,” Mrs. Oata says, before her husband comes in. “He will not explain things on his own.” She laughs and leaves the room.

Life-changing swaps

As Mr. Oata, dressed in a warm shirt and vest, walks me through his library I scan the names on the shelves. “Only Time Will Tell” and “The Sins of the Father,” by English novelist Jeffrey Archer. Next to them is Paulo Coelho, from Brazil. There are books by Jane Austen, Dan Brown, and Majgull Axelsson, a Swedish journalist.

He speaks hesitantly, in a soft voice. But once he starts chatting about books, his voice overflows with enthusiasm.

Born in Kashmir, the eldest son of a plumber and a housewife, he left home at 16 in search of work to support his family. He moved across India, from one tourist destination to the next, selling Kashmiri arts and crafts. He still regrets not completing his formal education.

Now and then, he noticed tourists at his stall holding books. One day, a man handed one to Mr. Oata, who asked him to summarize its contents. From then on, he asked book browsers if they’d be willing to swap, and tell him what the story was about – “and they would do it happily.”

Over the years, he moved to India’s southeast, then west to Karnataka, selling jewelry, shawls, rugs, and hand-embroidered bags. Over time, he collected hundreds of books, mostly by international authors, and created his first small library.

But he yearned to come back to the Kashmir Valley. So after much deliberation, he packed his books and went home in 2007.

“I feel writers are always alive forever through their books, even after death, and for me that is such an interesting aspect,” Mr. Oata says, adding that his books are his “most precious possession.”

“Though I cannot read, I can remember most of the books: their theme, the name of the author, and the country that the author belonged to,” he says. “I have remembered it all by remembering the color of the book, its cover page, and symbols.”

Take the very first book he received: “The God of Small Things,” by Indian writer Arundhati Roy. Mr. Oata still vividly remembers the messy story of a family, tangled over decades.

He picks up another. “This is about a brave man, who is at war with injustice,” he says. “The theme of this book reminded me of my birthplace, Kashmir, and so it is embedded in my memory.” The book is “Asking for Trouble: The Autobiography of a Banned Journalist” by Donald Woods, a South African persecuted by the country’s apartheid government.

The long wait

Back in Srinagar, Kashmir’s largest city, Mr. Oata started a travel agency and a handicrafts store. Space at home was tight, and his family griped about all the books in the way. One day his mother offered to sell them to a scrap dealer; Mr. Oata rushed home to stop her.

He realized that if he wanted to keep them they needed a permanent home, so he put a library in his store and opened it to visitors. It was a success, and he became a popular stop in the area for tourists who would read, leave a gift, or exchange a book. One French tourist helped organize the books in alphabetical order.

But challenges also came. In 2014, the Kashmir valley flooded and inundated the shelves. “When I saw my library, I cried like a child,” Mr. Oata says. For months, the whole family dried and cleaned the books, then shifted the library to the second floor.

Then came Aug. 5, 2019. The Indian government scrapped the special status of Jammu and Kashmir and imposed direct rule from New Delhi. Authorities imposed a media blackout, cutting the region off from the rest of the world.

With no tourists, Mr. Oata had no visitors. As Kashmir endured months of curfews, shutdowns, and blackouts, he lived on savings – only to see COVID-19 restrictions imposed last spring.

To make ends meet, he began working as a wage laborer, when there was work; his wife did the same. They aspire to provide their children with education and opportunities. Their daughter is a first-year medical student, and their son is a senior in high school.

With Mr. Oata working away from the library, his wife “takes care of it really well,” he says, a half smile on his face. “But whenever I get time I come here, touch, feel, and smell [the books], with this constant hope that things will become normal again, and my library will once again thrive with people.”