Responsible or reckless? India brings back the long-lost cheetah.

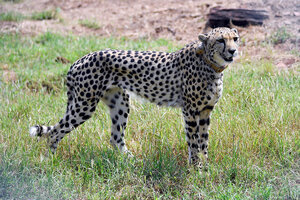

A cheetah explores Kuno National Park in Madhya Pradesh, India, Sept. 17, 2022, after it was released by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. It's one of eight cheetahs flown in from Namibia that will be monitored 24/7 via tracking collars.

India's Press Information Bureau/Reuters

New Delhi

The world’s fastest land animal is making its way back to India – slowly.

On Sept. 17, decades after the species was declared extinct on the subcontinent and 13 years after conservation efforts to reintroduce the big cat began, eight African cheetahs scurried into the Kuno National Park in Central India’s Madhya Pradesh.

More will follow, say conservationists, but these eight – five females and three males – represent a big feather in India’s cap to restore a lost treasure. However, the first-of-its-kind transplant from Namibia also has many critics. Some believe the $11 million project is a waste of taxpayer money, and question whether the long-extinct species can thrive beyond captivity.

Why We Wrote This

Advocates of India’s cheetah reintroduction project say they’re driven by a sense of national responsibility. But others argue the single-minded push to bring back the big cat is more reckless than responsible.

But proponents say they have a responsibility to try.

“The only mammal that has been lost in independent India is the cheetah. So it becomes our moral and ethical responsibility to bring them back,” says S.P. Yadav, member secretary of the National Tiger Conservation Authority and head of the cheetah reintroduction project.

He hopes the project will also be an inspiration for other countries that have lost important animals.

Historic milestone

Cheetahs were declared extinct in India in 1952, only five years after the country gained independence from the British. Plans for repopulation began that same year.

There are fewer than 8,000 cheetahs left in the world today, including about a dozen Asiatic cheetahs, a slimmer subspecies that once roamed India and is now found only in Iran. In the 1970s, India attempted to get Asiatic cheetahs from Iran in exchange for Asiatic lions, but negotiations failed after the shah was deposed.

The current plan to use African cheetahs has been in the works since 2009.

The imported cats were accompanied by wildlife experts, veterinary doctors, and biologists during their transcontinental flight from Namibia to the Indian city of Gwalior, where they were transferred by helicopter to Kuno National Park, a sprawling sanctuary populated with prey such as antelope and wild boars. India’s Environment Ministry says this is the first time a large carnivore has been transported across continents in order to establish a new population.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who released the cheetahs into the park, called their arrival a “historic” moment for India.

Yadvendradev Jhala, dean of the Wildlife Institute of India and one of the experts tasked with this conservation initiative, says they have a permit to acquire 20 cheetahs – the eight from Namibia and 12 more from South Africa, which will arrive at Kuno National Park later this year.

The Indian government plans to introduce at least 50 cheetahs into various national parks over the next five years.

Initially, they’ll be kept in an electrified enclosed area so they can acclimate to the local environment before being released into the open. The Namibian felines have been fitted with tracking collars and will be monitored 24/7 by officials.

“India now has the economic and scientific ability … to restore our natural heritage,” Dr. Jhala says, adding that the causes of their initial extinction – mainly overhunting – have been addressed through strict laws. He expects the cheetah restoration to boost ecotourism and local livelihoods.

But not everyone is on board.

“Fatally flawed”

Indian conservationist and big cat expert Valmik Thapar says the project is “fatally flawed” because the country lacks the vast habitat or wild prey needed to sustain a significant cheetah population.

“Even in the best cheetah country, the Serengeti cheetahs are struggling,” he says. “So what is the sense in bringing them to India unless you want them in captive enclosures?”

The cheetahs are expected to remain in enclosures for three months, where food is provided. “The problem will come after three months when they are released and have to hunt forest deer, or encounter leopards and hyenas,” says Mr. Thapar.

Others believe the government’s first responsibility should be to protect the species that still naturally exist on the subcontinent, including those found in its disappearing grasslands.

Abi Tamim Vanak, a wildlife biologist, says the cheetah project has been “touted as an important opportunity” for saving India’s endangered savanna ecosystems, but organizers have yet to propose a clear plan for how they’ll conserve these biomes beyond the protected reserves.

This also throws cheetahs into an ever-shrinking habitat.

“The government has gone with the old ‘fortress’ conservation model,” he says, referring to the controversial belief that conservation is best achieved by creating separate spaces for humans and wildlife. Authorities are bringing cheetahs “into what will only remain glorified safari parks in the foreseeable future,” Dr. Vanak says.

Grassland restoration

Proponents hope the grassland restoration and cheetah repopulation will flourish in tandem.

“When the cheetah was not there, there was not much motivation to protect the grassland habitat,” says Dr. Yadav, the project’s leader. “Now that you have a charismatic species, there is a drive to protect that landscape. … I’m 100% sure that this will help revive other endangered species.”

For Wildlife Conservation Trust President Anish Andheria, the project’s success hinges on whether it leads to an increase in the country’s grassland habitats.

“If the cheetahs can be used to get funds to protect grasslands, and we can expand the grasslands in the next 10-12 years, then the cheetah [program] would have fulfilled its purpose,” he says. “But otherwise, an addition of one more carnivore … is not going to solve much.”