Amid British furor over Afghan rescue mission, war support plummets

The day after New York Times reporter Stephen Farrell was released by British commandos, a new poll finds growing opposition to the UK's troop commitment to the war.

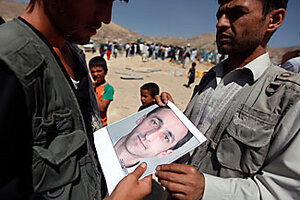

Afghans look at a picture of Afghan reporter Mohammad Sultan Munadi, who was killed in a rescue attempt by British commando to free him and his British colleague Stephen Farrell from kidnappers, during his funeral at a cemetery in Kabul on Thursday.

Ahmad Masood/ Reuters

London

A storm of controversy in Britain over a deadly rescue mission in Afghanistan is coinciding with a new poll that shows plummeting support for the war – something that could strain US ties with its closest NATO allies and present more obstacles to President Obama's push for the alliance to send more troops.

Britain is the second-largest contributor of troops to the NATO mission. But doubts about conflict's direction have turned Britons hostile towards an increased military commitment there.

Widespread allegations of election fraud are undermining international support for Afghan President Hamid Karzai. And the rescue of kidnapped journalist Stephen Farrell, which resulted in the deaths of one commando and Mr. Farrell's interpreter, Sultan Munadi, has only underscored concerns about a rising military death toll.

The new poll, conducted by the German Marshall Fund, asked voters if they would support a request from President Obama to increase troop levels. Huge majorities across Europe were opposed, with 75 percent of Britons and 86 percent of Germans saying Obama's request should be turned down.

The poll also found that 41 percent of Britons want their troops withdrawn entirely and a further 19 percent want the troop level reduced. The poll found 41 percent of Germans want a full withdrawal and 16 percent want a troop reduction.

Majorities in all countries surveyed indicated increasing support for economic reconstruction, except in Britain, where 49 percent approved.

Polling was carried out in late June, before both the daring commando raid to free Mr. Farrell on Wednesday and a German airstrike last Friday that killed 70 people, some of them civilians, in the previously quiescent Afghan province of Kunduz.

Both events, at least for now, have increased opposition to the war.

In pacifist-leaning Germany, the deadliest combat strike by German troops since World War II has become a hot campaign issue, with the country headed for elections at the end of the month.

In Britain, the operation to free Farrell might have been widely greeted with somber pride in another climate, but instead, questions are being raised about the wisdom of going ahead with the raid.

Criticism of journalist

Military commentators have criticized Farrell, a respected journalist with joint British-Irish citizenship who was also briefly abducted in Iraq in 2004, for apparently ignoring warnings not to venture into a Taliban-controlled area where he was kidnapped.

Farrell told The New York Times, his employer, that he had received information that the road to the village hit by the airstrike and where he was taken hostage, was safe.

Britain's beleaguered Prime Minister Gordon Brown is also drawing flak as a result of the raid, which the British government today confirmed was sanctioned by Mr. Brown's defense and foreign ministers following consultations with him.

"Ordinary people everywhere are now saying that the government has got to provide a time scale for withdrawal," says Rose Gentle, a Glasgow mother whose son died serving in Iraq and who now jointly chairs the campaign group Military Families Against the War.

Brown battles to shore up support

Unnamed hostage negotiators who were said to be within days of securing a peaceful release expressed anger at the decision to stage the operation, according to The Times of London.

The episode comes as Brown and his cabinet are battling to shore up support for the war. On Wednesday, a survey published by Britain's National Army Museum showed that 53 percent of Britons now disagreed with the initial decision to deploy British troops to Afghanistan, while just 25 percent said they agreed.

Those figures are broadly in line with European sentiment. The Marshall Fund poll found that 63 percent of Europeans are pessimistic about stabilizing the situation.

But the level of opposition in Britain, regarded as more of a rock of support for the conflict until now, may shock planners in the White House, Downing Street, and NATO headquarters.

Jonathan Tonge, professor of politics at the University of Liverpool, says the changing British public view of Afghanistan was now reminiscent of attitudes towards the decades-long conflict in Northern Ireland, when the public was almost always in favor of pulling troops out, apart from a few occasions when infamous IRA attacks enraged public opinion and caused a spike in the opposite direction.

"Part of the reason is the escalating number of fatalities among troops, but people are also not clear on how long this will last for, they are unsure if the war is winnable, what victory will look like, and whether it really has any effect on reducing the terrorist threat at home, where many terrorists have turned out to be homegrown," he says. "If you polled people after 9/11, there was a gung-ho attitude toward going in, but that has evaporated."

Mr. Tonge predicts that both Labour and the opposition Conservative Party will soon be exploring options for a quiet exit from Afghanistan.

Tonge does not expect Afghanistan to become a major election issue, as it has in Germany, where a resurgent left is using it to attack Chancellor Angela Merkel. Instead, he says, the political consensus in Britain is beginning to crack.

Election fraud

Both the Conservatives and Britain's third major party, the Liberal Democrats, are preparing to call for the disputed Afghan election to be re-run, while the Conservative leader, David Cameron, regarded by many as a prime minister in waiting, was recorded Wednesday by a BBC camera crew lamenting "naked" fraud in Afghanistan's election.

Although his remarks were said to have been private, there are suspicions that his party may be preparing to open up blue water between it and the government.

But the strategy that political pundits say Cameron is considering would hinge on sending in more British troops for a short duration to train the Afghan Army.

Brown is also facing mounting opposition within his own party, which may explode into open political civil war at Labour's annual conference later this month. Long-term antiwar activists sense the wind is now in their sails.

"When it came to Iraq, we were told it was about weapons of mass destruction. With Afghanistan, it was terrorism, and perhaps people thought it was a 'good' war because of that," says Ms. Gentle. "But now we are at a turning point. Everywhere you go, you bump into people who know or are related to someone serving in Afghanistan, or have a relative there. Anytime a soldier gets killed, the ripples get bigger."

___

Is Afghanistan worth fighting for?

Former national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski is skeptical about a troop surge, while Francis Fukuyama, author of "The End of History and the Last Man," sees reasons to persist.

___