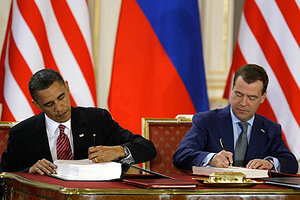

Obama, Medvedev sign START treaty on nuclear weapons, but Russia is uneasy

President Barack Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev signed the START treaty on nuclear weapons today. While both hailed the missile reduction pact as a landmark, Russia is uneasy about its strategic future.

US President Barack Obama, left, and his Russian counterpart Dmitry Medvedev sign the newly completed 'New START' treaty reducing long-range nuclear weapons at the Prague Castle in Prague, Czech Republic Thursday.

Mikhail Metzel/AP

Moscow

Presidents Barack Obama and Dmitry Medvedev flourished their pens and signed the START nuclear missile reduction treaty in Prague today. The deal was a year in the making and represents the first major strategic accord between the former superpowers since the end of the cold war.

It was a warm and smile-filled "kumbaya" moment for the US and Russia, whose relationship has seen some stomach-churning ups and downs in recent years. President Obama hailed the agreement as an "important milestone for nuclear security and nonproliferation and for US-Russia relations."

But the gloomy signals coming out of Moscow this week suggest that the Russians harbor serious doubts about the viability of the treaty they just signed and even deeper misgivings about Barack Obama's changes to US nuclear weapons doctrine that are ostensibly aimed at moving toward a nuclear weapons-free world.

"We are seeing, in sharp relief, that the US and Russia view the strategic landscape through completely different lenses," says Dmitry Suslov, an expert with the Council on Foreign and Defense Policies, a Moscow think tank whose members include top Kremlin advisers. "Moscow is laying down the message that this new treaty is fine, but we should not interpret this as a new era in relations. The strategic picture is changing in ways that Russia is not completely comfortable with, and we need to keep our options open."

In a wide-ranging press conference Tuesday, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov shocked many by warning that Russia might pull out of the treaty if US plans to station strategic anti-missile interceptors in Europe, which were suspended by Mr. Obama last year, are revived during the 10-year life of the START agreement.

"If and when our monitoring of how those plans are implemented shows they are entering a stage of creating strategic missile defense systems ... we will have the right to resort to [withdrawal] provisions provided in this treaty," Mr. Lavrov said.

He also made clear that Russia is not open to the further cuts in nuclear arsenals that the White House is already pressing for, and appeared to wonder out loud whether Obama's campaign for a nuclear weapons-free world wasn't part of an American plot to dominate the globe via its supremacy in conventional arms.

"We believe the ultimate goal of a world without nuclear weapons is very important," he said. "[But] world states will hardly accept a situation in which nuclear weapons disappear, but weapons that are no less destabilizing emerge in the hands of certain members of the international community."

Some experts say Lavrov was addressing domestic skeptics, including the powerful prime minister, Vladimir Putin, who has publicly criticized the treaty.

"President Medvedev is very worried about possible domestic opposition to this treaty," says Viktor Kremeniuk, deputy director of the official Institute of USA-Canada Studies in Moscow. "Several parties in the Duma, including United Russia [which is led by Putin], and the Communists, have expressed doubts. Medvedev sees a ratification battle looming."

Disappointed Moscow

But Lavrov's tough language also reflects Moscow's deep disappointment that the accord contains no firm link between the substantial cuts both sides will be making to their stocks of offensive atomic weapons and Russia's demand for follow-on negotiations to limit strategic missile defense. Many in Moscow fear that a US technological breakthrough in defensive weapons might undermine its aging strategic deterrent, which is heavily deployed on land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles.

"Though the exact text isn't known, it's clear that there is no direct connection between offensive and defensive weapons in the treaty," says Pavel Salin, an expert at the independent Center for Political Consulting in Moscow. "Russia faced a difficult dilemma: either to refuse to sign this document, or meet American interests under special conditions. It's no surprise that we're leaving ourselves a way out."

US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton appeared to confirm the lack of linkage, telling journalists Tuesday that "the START treaty is not about missile defense. It's about cutting the respective sizes of our arsenals – our strategic offensive weapons." She added that the US is committed to pursuing missile defense, but would "be working with the Russians to find common ground."

The first round of superpower arms control was opened with a deal to limit the development of defensive weapons, a technology that was then in its infancy. For three decades the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty acted as the keystone of subsequent accords that slashed superpower atomic arsenals from a total of around 40,000 strategic and tactical warheads in the early 1970's to a still-apocalyptic 20,000 or so today.

But George W. Bush withdrew the US from the ABM treaty in 2001, infuriating the Kremlin and setting up Moscow and Washington for what looks like a long-term quarrel over the future of missile defense.

Analysts say the central problem is that Russia depends heavily for security on its nuclear deterrent, while the US is moving toward a far more flexible strategic capacity based on high-precision conventional weapons.

"In the present setup, Russia enjoys parity with the US, and thus holds superpower status, thanks to its nuclear weapons," says Mr. Suslov. "Moscow's suspicion is that the US wants Russia to lose its nuclear weapons, while the US will enjoy overwhelming preponderance of conventional weapons. In that world, the US would be the sole superpower, with the ability to strike anywhere on Earth using strategic delivery vehicles armed with conventional warheads."

New Russia, US doctrines pull countries in opposite directions

Russia's recently adopted military doctrine actually increases the country's dependence on its nuclear forces and lowers the threshold for their use, while the Obama administration's new doctrine, made public this week, moves in exactly the opposite direction.

"Our military reform is not completed and our conventional weapons technology is rather outmoded," says Mr. Kremeniuk. "If we imagine there were no nuclear weapons tomorrow, Russia would be distinctly weak. That's why this START treaty is the end of the arms control road, for quite some time to come."

But a few experts argue that the terms under which this debate is being conducted in Russia are ill-focused.

"Russia cannot and should not aspire to strategic parity with the US," says Dmitry Trenin, director of the Carnegie Center in Moscow. "No amount of arms control negotiations will transform the relationship from adversarial to cooperative.... It's perfectly realistic to expect that the US will someday develop a workable anti-missile shield.

"The way to go is not to try to limit strategic missile defense, but to get on board, and develop a US-Russian collaboration in this area. That would be the game-changer," he says.

IN PICTURES: Nuclear Weapons