Europe's 'holy fools' set the tone for US Occupy Wall Street protesters

From Greece to Italy to Spain, young Europeans, much like the Occupy Wall Street protesters who have followed them, have been pushing for answers to high unemployment and poor representation.

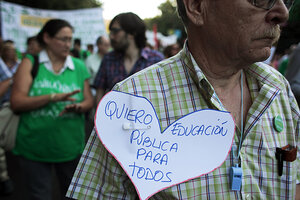

A man wears a heart shaped piece sign that reads "I want public education for everyone" as he takes part in in a demonstration against proposed budget cuts in public education in central Madrid, last week.

Susana Vera/Reuters

Paris

The economic protests capturing attention outside Wall Street and elsewhere in the United States germinated partly in Europe.

Before the “99 percent” concept caught fire in New York, a similarly ragtag set of characters, mostly young, were camping out in Spain, Greece, and Italy. They walked across Europe to Brussels with painted faces, formed hundreds of working groups, and generally acted out the ancient role of “holy fools” – outspoken nonconformists – in the modern age. Something is wrong, they agree, but they don’t know what it is. They have no political power. But in spite of it all, they aren’t going to accept an unendingly bleak present or future.

In France, an earnest-eyed newly unemployed young woman, Gaelle Simon, who moved home with her family after working in a Swiss factory, says typically: “If nothing changes, there is no way forward. I strongly feel this. Things have to change.”

Ms. Simon walked to Paris from Orleans. Like many tent city upstarts, she had been depressed. But joining the Don’t-Accept-It group changed that: “I felt I was being controlled by events, by everything, and that I had no say over this. Doing something, thinking independently, I felt a great new sense of energy.”

In tent cities at City University in Paris this summer, or in Madrid and Athens – where youth unemployment tops 40 percent – one heard the tropes of “99 percent” and Occupy Wall St: The economic system is stacked against ordinary people whose taxes are used to bail out banks and states coffers for bad decisions they didn’t make. Meanwhile, European austerity policies are eviscerating jobs.

Some here think they are at a European Woodstock or a transplanted Arab spring. Some young people wear masks – there’s a lot of “radical chic” – but there are also a lot of grandparents. Some talk about changing the world, some just want a job. They live on the Web, follow social networks, connect to kindred spirits in India, in Madison, Wisc., in Tunis, in Israel and Brussels. They don’t discuss strategies of violence. Many predicted this summer their disillusionment would jump the Atlantic and hit Wall Street. Few believed them.

On Oct. 15, there is planned global demonstration.

Utopian? No. I just want some representation.

“We are accused of being utopian.” says François, part of an economy talk shop at City University in September. “But if we were standing here in 1750 and we spoke of the world as it has become in 2011, people would have accused us of being utopian or crazy. OK, some of us want to do away with money, but a lot just want a better representative democracy.”

Some decry capitalism, many think it is useful. They admit to having no easy answers. They are mostly educated. A lot of them walk on the margins of the job market. In Europe, they speak of a kind of spiritual vacuum, a distress that goes past just their material plight and is bothering their souls. There’s a humanist dimension to this in secular Europe. Their dreams of an easy life have been upended. They don’t want to be consumerist robots. Their central hated phrase comes from politicians and financial elites who tell them “there is no alternative,” meaning no alternative to an endless condition of debt and shrinking possibilities.

It is hard to imagine some protestors on a morning commute to banks or insurance companies. They don’t wear suits. But as economist Paul Krugman wrote sympathetically about “the malefactors” in a recent New York Times piece, recent experience “has made it painfully clear that men in suits not only don’t have any monopoly on wisdom, they have very little wisdom to offer. When talking heads on … CNBC mock the protesters as unserious, remember how many serious people assured us that there was no housing bubble, that Alan Greenspan was an oracle, and that budget deficits would send interest rates soaring.”

“We live in what are called democracies, but the people don’t have much power,” says Thierry, a thirtysomething who has two kids and has a degree but is in and out of work: “We watch TV all the time and that’s made many people stop thinking. A lot of people [in our group] will agree with me when I say, if you want to be successful, you have to be dishonest. If you stick with your own sense of right and wrong, if you listen for your own honest voice inside, you become weak in the eyes of others. So you block that out. You try to become strong on the outside.

“Our system is more capitalist than democratic,” he continues. “What we want is a democracy with heart … a capitalism of the human spirit.”

Marginalized

The European protesters are quite marginalized. They refuse to join the political game. But in their view, finding answers is the job of the politicians. They are saying how they feel, no matter how foolish this may seem.

Harvey Cox of the Harvard Divinity School wrote in the 1970s on the “Feast of Fools” – a medieval European carnival that mocked the worldly powers of the day. Usually that meant the priests, bishops, and cardinals of the church in Rome. The European variants of Occupy Wall Street are playing out the feast with the elites of 2011. As Wikipedia denotes holy fools: The “spiritual meaning of ‘foolishness’ from the early ages of Christianity [meant a lack of acceptance] of common social rules of hypocrisy, brutality and thirst for power and gains.”

Inchoate or naive as it may be, that approximates the Occupy Wall Street spirit on this side of the Atlantic.