With US-Russia relationship toxic, Moscow looks to strengthen ties with China

China's new President Xi Jinping chose Moscow, where he arrived Friday for a three-day visit, to be his first foreign destination, highlighting strengthening ties between China and Russia.

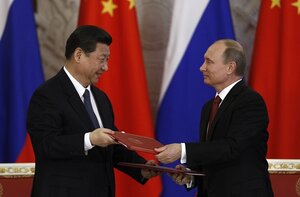

Russia's President Vladimir Putin (r.) exchanges documents with his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping during a signing ceremony at the Kremlin in Moscow today.

Sergei Karpukhin/Reuters

Moscow

It's probably no coincidence that newly-minted Chinese leader Xi Jinping chose Moscow, where he arrived Friday for a three-day visit, to be his first foreign destination.

Over the coming weekend Mr. Xi will huddle in the Kremlin with President Vladimir Putin, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, and other Russian officials to discuss the usual list of items on the two countries' burgeoning bilateral trade agenda: Russian gas, oil, arms, and engineering goods in exchange for Chinese consumer products. Official sources say they expect about 30 agreements to be signed, mainly in the field of energy.

But underlying that is a growing sense that the two countries are being driven together by shifting geopolitical winds, which are alienating each from the West while intensifying the need for more reliable partnerships. As Xi arrived in Moscow Friday, Mr. Putin stressed that ties between Russia and China have never been stronger, and they are set to grow warmer still.

"Our relations are characterized by a high degree of mutual trust, respect for each other's interests, support in vital issues. They are a true partnership and are genuinely comprehensive," Putin told the official ITAR-Tass agency.

"The fact that the new Chinese leader makes his first foreign trip to our country confirms the special nature of strategic partnership between Russia and China," he added.

In China's case, all the recent talk in the US of a "pivot to Asia" has Beijing worried that it may be in danger of being isolated by US pressure. China's standoff with Japan over the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands in the East China Sea, with the attendant danger of drawing in Japan's main ally, the US, could be focusing Chinese minds on the desirability of strengthening relations with Russia.

Indeed, some Russian experts suggest that Xi will likely find a delicate moment to remind Putin that Moscow, too, sometimes gets exasperated with "Japanese bellicosity" in the matter of Russia's longstanding territorial dispute with Japan over the far eastern Kuril Islands which were seized by Soviet forces in the waning days of World War II.

"The US is shifting its priorities from Europe to Asia. That suggests some sort of competition in this arena is inevitable," says Alexander Konovalov, president of the independent Institute of Strategic Assessments in Moscow.

"Everyone is trying to find the strongest partners for this new situation, and Russia is one of the most desirable partners to have [for China]…. And this fits with the needs of Putin, who needs some dramatic successes in foreign policy at this point. He may well seek to forge a stronger partnership with China," he adds.

From sour to toxic

The pressures driving Russia to pivot eastward are even more clear.

Over the past year Moscow's relations with Washington have turned from sour to toxic, and many policymakers in Moscow say they're no longer even interested in being friends.

The European Union – which is still, officially, listed as a top priority in Russia's foreign policy doctrine – is beset by financial crisis. It is actively working to reduce its dependence on Russian energy supplies and, to top it off, last week attempted to bail out banks on the Mediterranean island nation of Cyprus with a special tax that would have hammered thousands of rich Russians who keep bank accounts there.

Russia and China have joined together to veto Western-sponsored resolutions in the UN Security Council that might enable outside involvement in Syria's ongoing civil war, and both tend to share a common allergy to all talk of "humanitarian intervention" in any of the world's trouble spots. Experts say they share similar views on how to contain the nuclear ambitions of North Korea, and also the need to prepare for instability emanating from Afghanistan after the US and NATO allies draw down their forces next year.

"A number of things are converging at the same time," says Alexei Pushkov, chair of the State Duma's international affairs committee.

"Countries like Russia and China look at the traditional power centers – the US and Europe – and see that these countries cannot provide answers. Everyone has the feeling that the old world order is finished. This cascade of events drives Russia and China further from reliance on the Euro-Atlantic world. After all, what kind of example do they provide if they just confiscate money from peoples' accounts?" he says.

"Russia, China, the other BRICS countries, are looking for a new model…. It's not driven by some sort of anti-Western logic. There is a crisis of trust. There is a feeling that our countries are on their own. We don't have a point of reference anymore."

Reasons for Russia-China partnership

On the other hand, Mr. Pushkov says, the positive logic for Russia-China partnership keeps growing.

"We look at Beijing, and we don't hear them lecturing us about human rights and how to conduct democracy. There is no missionary element on either side. But there is strong economic incentive. The Chinese economy is a factory, and we have the energy to power that factory. That's a pretty solid basis," he says.

Russia-China trade turnover has been growing steadily for years, and it jumped by more than 11 percent in 2012 from $88.1 billion the previous year. Official forecasts see it hitting $100 billion by 2015 and $200 billion by 2020.

China now imports about 8 percent of its crude oil from Russia, most coming through the newly-built Skovorodino-Mohe pipeline, which runs to Daquing in northeast China.

But the commodity that's likely to dominate talks this weekend is natural gas. Russia's state gas monopoly Gazprom agreed last year that it will construct a major new pipeline in the far east that could deliver up to 68 billion cubic meters of gas to China annually for 30 years. Among other things, such a deal might save Gazprom, whose profitability has been dropping as global gas prices fall and traditional customers in western Europe launch damaging court cases against what they allege are Gazprom's "anti-market" practices.

Russian and Chinese negotiators have been haggling for years over the price of the gas and, although Chinese sources say they're hopeful of a breakthrough this weekend, the Russian side insists that no agreement is near enough to be settled during Xi's visit.

Russia, formerly a major arms exporter to China, has lately been reluctant to sell its most sophisticated weaponry to the Chinese out of fears that they may be reverse-engineered and used to create Chinese products that could eventually compete with the Russian versions in international arms markets.

But Russia has recently agreed to sell 24 advanced, multirole Sukhoi Su-35 fighters to China. And, according to a new report from the Carnegie Endowment, Moscow may now be willing to help China in areas where it lags technologically, such as aircraft engines.

In the longer term, Russia desperately needs Chinese investment, labor, and expertise in its drive to develop its vast Siberian territories . But here, Russian experts say, is the biggest reason that despite all strong arguments for tighter relations, Russia may continue to hold China at arm's length: Siberia, though rich in resources, is virtually devoid of population. Next door China is teeming with people and explosive economic energies.

In an interview with Russian state TV Thursday, Xi was emphatic in his insistence that all previous border disputes with Russia have been resolved "once and forever" and that China will never pose a military threat to anyone.

This may be enough to calm Russian anxieties, at least for now.

"We are facing major geopolitical challenges from the West all the time. But we don't hear anything from China that would make us worry," says Pushkov.

"Of course, it might look different if China were to change, and become a more nationalistic and aggressive nation. But, for the time being at least, China has shown itself to be a moderate, reasonable power that we can work with."