Is revolution afoot in Irish politics?

The longstanding dominance of Ireland's two main parties is under pressure amid ongoing economic woes. New party Renua has formed on the right, while interest has surged in parties on the left.

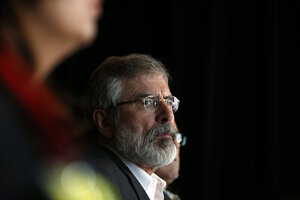

Gerry Adams' Sinn Féin party is polling at 19 percent, riding a wave of popular frustration with the current state of affairs in Irish politics.

Cathal McNaughton/Reuters

Dublin, Ireland

When Irish Prime Minister Enda Kenny took office in 2011, riding a wave of discontent following the 2008 economic crash, he promised a “democratic revolution.” He may be about to get one.

Ireland is Europe’s fastest-growing economy, with a 4.8 percent growth rate last year. But it has not yet fully recovered from 2008. Unemployment tops 11 percent, though government spending on social programs has held steady. Investment in infrastructure has collapsed, while a lack of construction has sent rents and house prices surging in the Dublin area. And new property and water taxes are pushing thousands to the streets in regular protests against the long-stable governing coalition of center-right Fine Gael and center-left Labor.

On St. Patrick's Day, government ministers have, as is traditional, jetted off to sell Ireland on the international stage, hoping to drum up goodwill off the holiday. But discontent at home is palpable. Promises of a dramatic change in policy now ring hollow and demand for change is rising – along with a final end to austerity.

The pressure threatens the longstanding dominance of Ireland's political duopoly – leading party Fine Gael and its bitter opponents Fianna Fáil. The augers thus far are not pointing to anything as dramatic as the rise of the far-left Syriza Party in Greece, but Irish politics has been led by these two parties since 1922, so even a tremor could feel like an earthquake.

"There's a definite mood for change. But whether the vehicle exists for it is another question," says Larry Donnelly, law lecturer at the National University of Ireland in Galway.

"In the US there's too many conviction politicians; in Ireland, there's too few," says Mr. Donnelly, who argues that a change could bring Ireland more in line with politics as it plays out in the United States and most other European countries. "There could be an injection of ideology into Irish politics ... [so] we could get a left-right divide."

The rise of the left

As popular frustration has deepened, the left has seen its fortunes improve, with Irish Republican party Sinn Féin on the rise, along with the far-left Socialist party. Sinn Féin in particular is wooing potential voters from Labor, which is widely viewed as having failed to have softened the worst blows of austerity.

The right is seeing movement as well, with new player Renua jumping into the febrile Irish political arena. A play on the word “renew” and Ré Nua, the Gaelic for “New Era,” Renua was founded by former government minister Lucinda Creighton, who quit her position in 2013 over the introduction of legislation to permit abortion in limited circumstances.

Party co-founder Eddie Hobbs, a financial adviser and well-known television personality, sees a popular desire to broaden the political options.

“The people don’t want the existing [political] brands to change – they don’t want the existing brands [at all],” he says.

Renua – which says it isn’t anti-abortion, and promises a free vote on the issue – is making an appeal to the center-right in the model of a classic European liberal party: fiscally conservative and socially liberal. This is not entirely new territory. During the 1980s and 1990s, the Progressive Democrats, a splinter from Ireland’s other major party, Fianna Fáil, made a similar pitch. Despite never amounting to a mass movement, it was able to wield an outsized influence through proportional representation.

Mr. Hobbs says his party is part of a decentralizing “global shift” toward a politics focused on empowering individuals and consulting with them on matters of policy. As a result, the party has pledged itself to open government, including releasing official government documents within days instead of decades.

Prime Minister Gerry Adams?

Sinn Féin's opinion poll success is occurring despite three consecutive, high-profile sex-abuse scandals and ongoing investigations into the past actions of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), the now-disarmed militant group associated with the party.

Despite allegations related to the cases and ongoing questions about Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams’s alleged role in the 1972 murder of Jean McConville, the party is polling at 19 percent – not enough to form a government, but enough to form one in coalition.

With an election due in 2016, Sinn Féin is now considered a contender and has aligned itself with Greece's Syriza.

Sinn Féin is already in government in British-administered Northern Ireland; achieving power in both Irish states on the anniversary of the Easter Rising that birthed the Irish Republic would be a major coup.

Dr. Graham Finlay, a political scientist at University College Dublin, says the prospects for a new force in Irish politics are better on the left than the center-right, primarily because Renua’s political position isn’t distinctive enough.

“I think the water [tax] protests and rise of Sinn Féin represent an actual change in politics. With Renua, though, beyond the charisma of Lucinda Creighton, the party is quite bizarre. It doesn’t even stand for the values that saw her leave Fine Gael in the first place," he says. "There might be space on the socially conservative right, but that’s not what where they’re heading for.”