Social media: Did Twitter and Facebook really build a global revolution?

Social media: From Iran to Tunisia and Egypt and beyond, Twitter and Facebook are the power tools of civic upheaval – but social media is only one factor in the spread of democratic revolution.

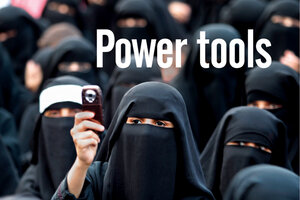

In Yemen, a cellphone camera is used at an anti-government rally. This is the cover story of July 4 issue of The Christian Science Monitor weekly magazine, focusing on Facebook, Twitter, and the limits of social media as the power tools of civic upheaval.

Reuters photo/John Kehe illustration

New York

It felt like we watched it everywhere.

Facebook pages blared protest plans. Photographs were uploaded to Flickr, a photo-sharing website, and video clips were hoisted onto YouTube. Protesters mapped their uprisings, and the violence that followed, adapting their online cartography in real time to reports gathered by text message and Facebook updates.

To say nothing of all the tweeting.

IN PICTURES: Top Twitter Moments

After only a few weeks watching the events in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, it seemed conclusive: This was the global revolution that Twitter built – that, maybe, only Twitter and other technologies could have built.

"These technologies collectively – everything from cellphone cameras to Twitter – are disruptive not just of other technologies like landlines or newspapers, which the military could shut down, but [of] the whole social construct. Social media is really a catalytic part," says Peter Hirshberg, a senior fellow at the Annenberg Center on Communication Leadership & Policy at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

If this all sounds a bit familiar, it should. Two years ago, Iranian pro-democracy activists protested against the re-election of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, as the world watched its Twitter feeds. In a country with so few foreign journalists on the ground, and where information was so tightly managed, the Green Revolution was quickly dubbed "the Twitter revolution."

When the uprising was crushed, the "cyber-topians," as one writer calls the digital revolution enthusiasts, were chagrined. They seemed naive for believing that even "Tweets heard round the world" would bring democracy with them.

But when Tunisia's and Egypt's corrupt autocrats fell earlier this year, the cyber-topian dream was resurrected. No one knows if the uprisings that have spread to Syria, Yemen, and Bahrain will be as successful, but governments everywhere appear to be watching their backs, asking themselves: Could a simple text message, sent by enough people, depose dictators everywhere?

Social media and the Arab Spring

It depends, literally, on who's getting the message. Analysts and observers say social media networks were used in the Arab Spring in two distinct ways: as organizing tools and as broadcasting platforms.

"Without social media," says Omar Amer, a representative of the Libyan Youth Movement, based in Britain, "the global reaction to Libya would have been much softer, and very much delayed."

News of the Tunisian uprisings spread rapidly on Twitter well before it was covered by global mainstream media. Al Jazeera English, the first outlet to jump on the story, relied heavily on social media to inform its reporting. "One protester in Benghazi told me, 'It is our job to protest, and it is your job to tell the world what is happening,' " says Mr. Amer, who administers a Facebook page for the youth movement.

Though the broadcasting capabilities of social media helped spread the story, the international euphoria about social networking may be misplaced when it comes to organizing uprisings. Deeply rooted cultures of online activism were more important than the newest social networking brands.

"Digital activism did not spring immaculately out of Twitter and Facebook. It's been going on ever since blogs existed," says Rebecca MacKinnon, cofounder of Global Voices Online, a network of 300 volunteer bloggers writing, analyzing, and translating news in more than 30 languages. She pegs the start of bloggers' networking and activism globally to 2000 or 2001. In Tunisia, she points out, it was not a known social media brand but a popular Tunisian blog and online news aggregator called Nawaat that played a key role in pushing events forward.

In Syria, in fact, one blogger says it was old-fashioned activism that pushed the digital world into the fight against President Bashar al-Assad.

"The street led the bloggers," says Marcell Shewaro, who left Syria for Cairo on June 19, after veiled threats from the government over her three-year-old Arabic blog, marcellita.com, which she says has about 50,000 readers a month. "Three months ago, I can't speak about Bashar, even in a restaurant. Now we are saying, 'OK, they [the protesters] are dying. What we can do is write. If we don't talk, it's now or never.' And stories are coming out, all over, even from the 1980s, because people are feeling they are not alone."

That feeling brought people together in a way that literally saved lives in Tahrir Square, says Yasser Alwan, a photographer in Cairo who spent more than two weeks in the square with protesters. "People built 20 sinks and 20 toilets, spontaneously," he says. "People brought blankets, donated tents – the third or fourth night it rained, and tarps appeared. A whole community was built in three or four days ... which is what allowed them to stay." Those same bonds, Mr. Alwan says, allowed them to surwvive the government's first siege of the square, on Feb. 2.

Jillian York, who has been following old and new media in the Arab world for several years, says the symbiosis between off-line activity and online activism is critical to how protests move forward.

"It's not just what the political climate is, but also what traditional activist networks look like," says Ms. York, director for International Freedom of Expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, an online digital civil liberties advocacy group. "Egypt had longstanding digital activists, who for a long time were using these platforms for their own causes.... They already [knew] what they were doing and how to use these platforms for activism, so when the time came, they knew exactly where to turn."

Most famously, the murder of Khaled Said, in 2010, prompted online outrage – and organizing. The young man was allegedly murdered by police in Alexandria, Egypt, after he posted a video of their corruption online. His death caused an outburst of online activism. Google executive and Internet activist Wael Ghonim started a popular Facebook page called "We are all Khaled Said," and the viral distribution of a morgue photograph of Mr. Said's disfigured face seemed to refute police attempts to deny the murder.

A quarter of all Facebook users in the Middle East are Egyptian, according to the second annual Arab Social Media Report by the Dubai School of Government. From January to April this year – the height of the Tahrir uprising – membership on the social site increased by 2 million, the report says.

Libya, on the other hand, has nothing like Egypt's Facebook numbers. "The average person in Libya doesn't use Facebook," says Libyan activist Taher Mohammed, who lives in Cairo. The numbers bear him out: Fewer than 5 percent of people in Libya even use the Internet, according to the United Nations' Human Development Report.

"Even for those who do," adds Mr. Mohammed, "how many young people in Libya really had the guts to use social media for activism before the revolution?"

Revolution before Twitter

Twitter and other social networking tools may be new, but the importance of an era's dominant media to the impulse to overthrow regimes has a much longer history.

"The media of the day has always been transcendent in revolutions. Printed pamphlets were powerful in the American and French revolutions. When [Ayatollah Ruhollah] Khomeini came back to power in Iran [in 1979], his revolution ... was spread by cassette tapes," says Mr. Hirshberg. "Today we have something new."

Fernando Espuelas, a United States-based media mogul who pioneered chat rooms in the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking Americas, remembers serendipitously witnessing the role of early social media in dissent a decade ago, in a country not often associated with digital activism. His visit to Argentina coincided with antigovernment riots that were spurred by the country's peso crisis.

On streets deadened by economic depression, "suddenly a group of protesters would appear out of nowhere," he remembers. "There was mass organization of neighborhood groups through the Internet.... There was no way to control popular opinion or behavior because it was being organized essentially invisibly in online communication – in the chat rooms and on the e-mail lists of early social media."

That experience stood out, he says, because, like much of the rest of the world, Latin America had long been gripped by brutal dictators whose rule relied on intimidation. As social networks have gotten more sophisticated, network specialists say, it's been harder for governments to maintain the kind of mass silence that corruption and abuse require.

"It's very hard to keep a secret, to keep people from communicating whatever they see," says Mr. Espuelas. "Therefore, the very simple tools of repression" – silence and secrecy – "are no longer operative, unless you're willing to use the ultimate tool, the Tiananmen Square approach of putting up tanks and killing ... people."

The "Great Firewall" of China

In today's China, more than a decade after the Tiananmen Square protests, the government would like to control the digital space as tightly as it controls physical space, making Arab Spring-style uprisings unlikely, even with the most sophisticated technology. The Chinese authorities do their best to censor politically sensitive news and information from social networking services, or SNS, and they are a lot better at it than any other government in the world.

"Unlike Egypt and Tunisia, where the regimes were technological Luddites, the Chinese are most sophisticated in understanding, monitoring, and manipulating social media," says Bill Bishop, an independent Internet analyst in Beijing.

They're also savvy enough to be afraid. A report last year from the official China Academy of Social Sciences think tank warned that social networking sites are "a challenge to national security." Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube are all inaccessible in China without sophisticated software that allow users to jump the censors' "Great Firewall."

Still, more than half of the 460 million-plus Chinese citizens with Internet access use copies of those networks, such as Sina Weibo, an enhanced Twitter clone, or RenRen, a Facebook look-alike.

With so many users sending so many messages, the tight control of Chinese cyberspace doesn't always keep information from getting out, especially on the Chinese version of Twitter.

"The speed with which politically sensitive information can spread on Sina Weibo is incredible; it's qualitatively different from blogs," says Xiao Qiang, a professor of journalism at the University of California, Berkeley, who studies the Chinese Internet.

Despite China's best efforts, that discourse often includes unsavory stories of government abuse. When a herder in Inner Mongolia was run over and killed last May by a coal truck, for example, and local people began protesting against Chinese-run coal mines, the censors unsuccessfully banned all mention of the demonstrations in traditional and new media, but the local authorities also moved swiftly to calm the situation using both security forces and promises of justice to the herders.

Sometimes, though, information slips through. Also in May, Qian Mingqi bombed three government offices in Jiangxi Province, killing himself and two other people. He had hinted at his intentions in one of his last postings on Weibo, the Twitter clone; his earlier posts described 10 years' worth of futile efforts to get compensation from the government for what he considered the illegal demolition of his home.

The bombing drew an enormous outpouring of sympathy and support from bloggers and Weibo users, who saw him not as a terrorist but as a victim of government injustice. After several hundred messages of condolence were posted on his Weibo account page, Sina, an Internet portal, closed it.

But cybersympathy is one thing, and real-world action is another. The Chinese approach, says Mr. Bishop, is to minimize the latter. "That's a fairly effective approach," he says.

A recent wave of arrests and disappearances of Chinese political activists suggests, not so subtly, that authorities won't tolerate online agitation moving off-line. Even if "the revolution will be blogged," as Professor Qiang maintains, he also acknowledges, "it will take time."

That's because Internet censorship isn't the only obstacle to a "Jasmine Revolution." Many Chinese feel they have too much at stake in their personal lives to risk rising up.

"I myself am angry," explains a former executive of a popular Chinese Internet portal who asked not to be identified by name. "But I have a house and a car and a job and I'd be worried that if I protested I would lose all this and not be able to protect my family. Under those circumstances, would you confront a tank?"

China is not the only iron-willed Internet censor in the region. Facebook is notoriously difficult to access in Vietnam, although the government denies it blocks the site, and in Burma (Myanmar), it's still almost impossible to send a text message, let alone a tweet.

Thailand's government closely monitors all of its media. During last year's Thai uprising, Facebook users actually amplified social divisions and stoked enmity across economic classes. As the July elections approach, though, the country's "red shirt" movement of rural and working poor is trying to dominate old and new media alike, says Supinya Klangnarong, who runs the Campaign for Popular Media Reform in Bangkok.

Meanwhile, Burmese dissidents use Thai Web access to communicate globally and push for democracy – and the Burmese government, of course, knows it. The pro-democracy news website Irrawaddy, run by Burmese in exile in Thailand, has faced increased cyberattacks over the past year, possibly run by a Burmese military unit in coordination with Burmese embassies overseas, says the organization's editor, Aung Zaw.

Cyberinterference can be effective to a point, as Egypt and Libya have discovered. Egypt leaned on the country's roughly 30 service providers to effectively shut off the Internet in late January, and in Libya, it's still difficult to get access. But newspapers, such as the postuprising publication Libya, founded in rebel stronghold Benghazi, use their satellite connection to communicate outside the country's main networks. Even some staff members at Quryna, a newspaper once controlled by Col. Muammar Qaddafi, privately used the paper's satellite to send information to foreign news agencies and post content on Facebook in the uprising's early days.

In Syria, meanwhile, blogger Ms. Shewaro says years of government censorship taught bloggers the tools they use now to circumvent controls – even as Syria sees online activism as a serious threat. "They learned a lesson from [former Egyptian President Hosni] Mubarak," Shewaro says. "Don't let the bloggers keep going."

The 'Internet in a suitcase' workaround

The ease with which governments can block the Internet for both broadcasting and organizing has been well known among techies, and workarounds are getting more attention. The Open Technology Initiative (OTI) at the New America Foundation has been developing "mesh networks" that can function for communication and organizing within repressive societies, even without greater Internet access. Their "Internet in a suitcase" is getting $2 million in funding this year from the US State Department.

"It's not really a suitcase," confesses Joshua King, staff technologist at OTI. He says the idea of mesh networks has been around since 2000 – at one point, this kind of network powered all digital communications across Athens. "You can provide local services on a network even if an Internet connection isn't available."

Meanwhile, it's not just government controls that can limit the effectiveness of social networks to spread dissent. It's the social media companies themselves. "We don't think about the fact that these are privately owned spaces. They're owned by companies, so our public sphere is in fact private," says York, of the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

User data is easy for these companies to track – and to share with governments, should the government ask for or require it. In 2005, Yahoo admitted to sharing, at the Chinese government's request, the user data of at least one person – Shi Tao, who Yahoo denied knowing was a journalist – when he posted antigovernment criticisms; Mr. Tao was sentenced to 10 years in jail.

Twitter has said it will hand over user data when "legally required," but that it will warn users before doing so. Facebook insists it does not share user data with governments, but analysts like York doubt that claim.

Companies' own internal policies, meanwhile, pose other problems for would-be digital activists. Facebook, for example, requires users to identify themselves with their real names, and any user can report another for an allegedly fake name, making very difficult the pseudonymity that much activism in autocrat regimes requires. YouTube prohibits users from uploading violent images, and in the early days of Libya's uprising, many videos were removed (the Google-owned site now has a more lenient policy for images coming from Libya).

Where revolution is just a tweet

However useful technology is at linking individuals and getting the word out, observers say Twitter alone won't generate successful uprisings. "Successful online activism has to have an off-line component," says York.

If the success of Egypt's uprising doesn't thoroughly demonstrate that belief, the failure of Uganda's might. This spring, hundreds of people took to the streets of Kampala for more than five weeks. Protesting rising food and fuel costs, and led by Kizza Besigye, a physician who lost a presidential bid to Yoweri Museveni in February, protesters thronged to Facebook and Twitter, where incremental news spread under the hashtag #walk2work. But if the movement seemed strong on Twitter, it failed to catch on in the streets.

Grace Natabaalo, a media trainer in Kampala, was glued to her computer, simultaneously following and sharing news on social networks. "I made a lot of noise about it, shared my ideas with people, posted whatever I could get on Facebook," Ms. Natabaalo says. "It was more about spreading information and pushing the debate forward, even if for the practical bit nobody went down onto the streets."

Mohles Kalule, project manager at the media monitoring organization Memonet, agrees. "The elite, the journalists on the social media, are just talking to themselves and not to the people," he says. Those people, he adds, have deep social divisions, and changing them will require a more powerful catalyst than instant communication.

And that suggests something that may be true in other countries, or even in parts of Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya. Even in countries with great Internet access for your average Joe, all that tweeting isn't always relevant.

"It is something there on the Internet, isn't it?" asks Ismail Mutongole. "For me, I don't use those things, as I don't have anyone to connect with on the Internet."

• Peter Ford in Beijing, Sarah Lynch in Cairo, Max Delaney in Kampala, Uganda, Simon Montlake in Bangkok, Thailand, and a correspondent in Hanoi, Vietnam, contributed to this report.