World's longest-serving death row inmate gets a retrial

Iwao Hakamada was convicted of killing four people in 1966, and sentenced to death. His lawyers successfully argued that DNA tests offer new evidence in the case.

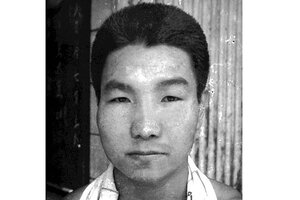

Iwao Hakamada (shown in an undated photo) has been on death row in Japan. A court suspended the death sentence and ordered him released for a retrial after 48 years behind bars. Guinness World Records lists him the longest-serving death row inmate. The court says DNA analysis obtained by his lawyers suggests investigators fabricated evidence.

(AP Photo/Kyodo News, File)

Tokyo and Austin, Texas

A Japanese court on Thursday ordered the release and a retrial of an aging prisoner accused of murder who served on death row for over 30 years, amid doubts about the evidence used to convict him.

Japan and the United States are the only two Group of Seven rich nations to maintain capital punishment and the death penalty has overwhelming support among ordinary Japanese.

Capital punishment is carried out by hanging and prisoners do not know the date until the morning of the day they are executed. For decades, Japan did not even officially announce that capital sentences had been carried out.

Iwao Hakamada, 78 and in declining health, was accused in 1966 of killing four people, including two children, and burning down their house in a case that soon became a cause celebre.

Though he briefly admitted to the killing, he retracted this and pleaded innocent during his trial, but was sentenced to death in 1968. The sentence was upheld by the Japanese Supreme Court in 1980 and Hakamada is believed to be the world's longest-serving death row inmate.

Hakamada's lawyers argued that DNA tests on bloodstained clothing said to be their client's showed that the blood was not his. That prompted presiding judge Hiroaki Murayama to revoke the death sentence and order Hakamada's release pending the retrial, terming the original verdict an injustice.

Hakamado's sister Hideko, who battled for decades to clear the name of her younger brother, now said to be showing signs of dementia, hailed the ruling.

"I want to see him as soon as I can and tell him, 'You really persevered,'" she told a news conference. "I want to tell him that very soon now, he will be free."

Prosecutors, quoted by media, said they would appeal the ruling.

Nearly 86 percent of Japanese feel that keeping the death penalty is "unavoidable," according to a government survey conducted late in 2010, and there has been little public debate. Experts say extensive media coverage of crime and worries about safety are behind the support.

Opponents point to the chance of innocent people being executed given that confessions form the basis of most convictions, with police often accused of using harsh tactics to obtain them.

Eight people were put to death in Japan in 2013, and there are believed to be nearly 130 on death row.

Meanwhile, in Texas, convicted murderer Anthony Doyle is scheduled to be executed on Thursday - even as many US states are finding it difficult to obtain the drugs used to execute prisoners.

Doyle, 29, was convicted of beating food delivery woman Hyun Cho - a South Korean native - to death in 2003 with a baseball bat, putting her body in a trash can and stealing her car.

He is scheduled to die by lethal injection at the state's death chamber in Huntsville at 6 p.m. CDT (2300 GMT).

Texas, which has executed more people than any other state since the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976, has obtained a fresh batch of its execution drug pentobarbital, the Department of Criminal Justice said this month, without revealing the source.

Many other U.S. states have been struggling to obtain drugs for executions after pharmaceutical firms, mostly in Europe, imposed sales bans because they object to having medications used in lethal injections.

Oklahoma has had to postpone two executions planned for this month because it could not find drugs. Alabama said this week it has run out of one of the main drugs it uses, putting on hold executions for 16 inmates who have exhausted appeals and face capital punishment.

Several states have looked to alter the chemicals used for lethal injection and keep the suppliers' identities secret. They have also turned to lightly regulated compounding pharmacies that can mix chemicals.

But an Oklahoma judge ruled on Wednesday the state's secrecy on its lethal injections protocols was unconstitutional, a decision that could delay executions in other states where death row inmates are planning to launch similar challenges.

The decision will have little impact on Texas, which plans to execute six inmates between now and the end of May, about the same number as every other state combined for the period, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, a monitoring agency for capital punishment.

If Doyle's execution goes ahead, he would be fourth person executed in Texas this year and the 512th in the state since the death penalty was reinstated.

But executions overall have been on the decline in Texas, after hitting a peak in 2000 of 40. Since 2010, Texas has averaged about 15 executions a year.

The high costs of prosecutions and the availability of a sentence of life without parole have caused capital punishment convictions to fall to about 10 or less a year in recent years.

"We are now very selective in what we choose to go after as death penalty cases, instead of deciding that every single murder that we try will be a capital case," said Susan Reed, the district attorney in San Antonio and a death penalty supporter.

(Additional reporting by Jim Forsyth in San Antonio and Heide Brandes in Oklahoma City; Editing by Lisa Shumaker and by Ron Popeski.)