Publishing children's books – and delivering them by elephant

Sasha Alyson hauls (sometimes by elephant) children's books in the local language to kids in rural Laos eager to learn to read.

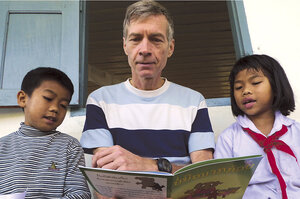

Sasha Alyson (c.) reads ‘New, Improved Buffalo’ – a book he wrote and published in Lao and English – to two children at the elementary school in Pakseuang village in Laos during a ‘book party.’ Mr. Alyson’s group, Big Brother Mouse, aims to ‘make literacy fun for children in Laos.’

Tibor Krausz

Luang Prabang, Laos

The little booklet contains riddles about animals – and the children in Pakseuang village just love it. Squeezing around a young Laotian staffer from Big Brother Mouse, the 40 or so second-graders listen with bated breath as he reads out the rhyming riddles to them.

"Buffalo!" "Snake!" "Frog!" they shout back their guesses. At each correct answer they jump up cheering with arms raised.

Books – even simple ones like the 32-page "What Am I?" – hold a magical appeal for Laotian children. Many of them have never seen a book, much less owned one.

"What struck me when I came here [as a tourist in 2003]," says Sasha Alyson, the American expatriate who founded Big Brother Mouse, a local children's publisher, "was that I never saw a book for children."

The literacy rate in Laos, an impoverished communist holdout of 6 million people bordering Vietnam, is around 70 percent. Yet most people have nothing to read besides old dog-eared textbooks and government pamphlets. At many village schools blackboards are the sole means of instruction, and children lack even pencils and paper.

"I knew I couldn't do education reform here," notes Mr. Alyson, who once ran a niche publishing firm in Boston. "But I could set up a small publishing project."

So he did. In 2006 Alyson obtained the very first publishing license in Luang Prabang, a historic northern town on the Mekong River where he now lives. He recruited several young locals he had met by chance: One was a waiter who wanted to become a writer, another a Buddhist novice monk eager to try something different.

The mission of the small but thriving enterprise, which has a bookish cartoon mouse as its logo, is to "make literacy fun for children in Laos."

On a recent Friday morning, Alyson and several of his helpers were in Pakseuang to hold a "book party" at the local elementary school. They led the children in playing games and singing songs with words like "Books are good/ Books make me smart."

The children then each had their pick from a stash of new books – and instantly lost themselves in them. Khamla, a shy 9-year-old with a Young Pioneer's red kerchief, chose "Animals of Africa." At a previous book party she received "The Monkey King" storybook.

"When I read, I feel happy," she says.

Based in a modest two-story house in Luang Prabang, Alyson and his two dozen helpers produce more than 30 new titles a year in print runs of 6,000 copies each: colorful alphabet books, science primers, fairy tales, and folk tales. All the books are produced in-house and most are written by "Uncle Sasha" and his Laotian staff.

"When I was 7, my parents bought me 'The Cat in the Hat.' That turned me on to reading," Alyson says. "Most Laotian children have no comparable memories. Many don't even know what a book is. Sometimes you have to show them how to turn a page."

Inspired by the playful style of Dr. Seuss, Alyson, who taught himself to read and write the Lao language, has penned more than two dozen children's books.

"New, Improved Buffalo," for one, tells the story of a village boy who outfits his trusted mount in various ways, much to the animal's dismay. Like all the publisher's books, it's printed on glossy paper and illustrated in a charming, idiosyncratic style by local teenage artists recruited from schools and villages through drawing competitions. It sells for just 15,000 kip ($2).

Alyson's team also sets local folk tales down in writing to preserve them and translates out-of-copyright foreign children's classics, retelling them in a local context. In its version of "The Wizard of Oz," illustrated by a 16-year-old Hmong boy, Dorothy is a girl called Kham who is swept away by a flood from Luang Namtha Province to the magical land of Oz.

Most of the books – and the "parties" at which they're given to children in 500 villages near and far – are sponsored by foreign donors, many of whom are tourists like Stuart and Alison McKenzie, a couple from Glasgow, Scotland, on their honeymoon.

"[Alyson and his staff] seem very engaged," Mr. McKenzie says. The couple paid for the book party in Pakseuang. "It's great to see children so happy with something we take for granted in the West," he adds.

Printing books is one thing. Getting them to children in remote villages is another. Alyson's helpers, several of whom are from Hmong and Khmu villages, regularly fan out across the rugged countryside.

Lugging stacks of books strapped to their backs, small teams undertake arduous days-long treks on foot, by boat – and at times astride Boom-Boom, a sturdy Asian elephant whose name means "books" in Lao. Boom-Boom now even has her own book, "The Little Elephant That Could."

In village after village they set up "junior libraries" for children in the bamboo hut of a local volunteer.

"Very few people read books in Laos," says Siphone Vouthisakdee, who is from a village where only five people have finished primary school. He now writes, edits, and designs books at Big Brother Mouse.

"But some children are becoming little bookworms," he says, "and take their books everywhere with them."

• For more stories about people making a difference, go here.