John Bergmann runs a special zoo for older, exploited, and abused animals

John Bergmann manages Popcorn Park, a special zoo in New Jersey that gives a home to distressed wildlife and exotic and domesticated animals.

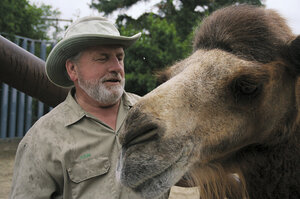

John Bergmann visits with Popcorn Park’s Princess, a Bactrian camel, known for her talent of picking the winner of professional sporting events.

David Karas

Forked River, N.J.

"The chickens crawl all over the office, and they lay eggs on my desk," says John Bergmann, who chuckles as he lifts up the towels that cover the papers in his office – which is in a barn. "It's all part of the job, I guess."

Mr. Bergmann is general manager of Popcorn Park, a federally licensed zoo nestled in the Pinelands of southern New Jersey that caters to distressed wildlife and exotic and domesticated animals. Part of the statewide Associated Humane Societies, the zoo cares for thousands of animals each year, including those that are ill, injured, exploited, abused, or older.

"Animals find their way to us," he says. "This all happened by accident."

The zoo began in 1977 as a pet adoption center when staff started receiving calls about distressed wildlife, including a raccoon that had been injured when it got caught in a trap.

As new animals came in, more cages were built, and piece by piece the zoo was born.

Today, more than 200 animals call the zoo home – including African lions, tigers, mountain lions, a camel, emus, wallabies, monkeys, bears, and, of course, the peacocks that roam the property and greet the more than 75,000 annual visitors in the parking lot.

On a recent morning, Bergmann made his rounds to the different cages, greeting the animals individually and calling them by name.

The routine is a familiar one for the animal residents, who treat Bergmann like a rock star. Chickens hitch a ride on the back of his golf cart, and tigers twice his size rise to greet him and gain his attention.

"You are around [the animals] a lot," he says of his occupation. "I guess there is some realization [by them] that you have done something for them."

Bergmann has bonded with each of the animals in his care, but Bengali is a special case. The Bengal tiger came to the zoo from Texas, where he had been rescued from an abusive, neglectful environment.

"He was emaciated ... you could see all his ribs and bones," Bergmann recalls. "The way he looked, it was like he didn't have a will to live."

The staff slowly nursed Bengali back to health. He underwent surgeries to repair broken teeth and other ailments. His largest challenge, though, was getting back up to his proper weight – 400 pounds – from 180 pounds.

It was when Bengali met an old lioness in the shelter next to his, Bergmann says, that he truly began to come alive. Each day, Bengali walked the fence to catch a glimpse of his new friend, until he finally built up the energy to walk his entire habitat.

"When he went out, he saw her, and he just got so excited," Bergmann said, smiling.

Today, when Bergmann visits, the massive tiger chuffs at him – a greeting – and rubs against the fence.

But helping animals recover from conditions like this isn't achieved by sticking to an eight-hour workday.

"It is sometimes a 24/7 job," Bergmann says. "Dante [a tiger] is feeling uncomfortable, [so] you stay here through the night."

Dante, much the opposite of Bengali, became afraid of a lioness in a neighboring cage after his companion died. It took many nights of comfort and coaxing to help him again become comfortable with his enclosure.

Bergmann credits his family with accommodating his unpredictable schedule – and his habit of occasionally bringing animals home with him to give them a little extra care and attention.

"My whole family has grown up with this," he says. His son, a veterinarian, works at the zoo, and his daughter, a teacher, uses animal themes in her lesson plans.

At the end of the day, Bergmann considers himself lucky.

"A lot of times you work seven days a week, and you don't even know it," he says. "You are doing what you love. You enjoy helping the animals out."

The staff has seen a wide range of animals find their way to Popcorn Park.

Porthos, a lion, was found in a converted horse stall with the floor caked with excrement. Doe, a deer, is so old she has gray eyelashes. And Princess, a camel, has a talent for picking the winner of sporting events.

"We take them when no one else wants them," Bergmann says, admitting that the zoo can sometimes resemble a retirement home for older creatures living out their senior years in peace.

The zoo also has a large kennel, which has high adoption rates for the household pets there. Many come from states with severely overcrowded animal shelters, where animals would not be held long before being put down.

The zoo runs primarily on donations, Bergmann says, which help offset the cost of its 42 staff members, including veterinarians and animal control officers, who provide constant care for the animals.

And that doesn't include supplies and specialty food items needed to accommodate the picky eaters among the menagerie.

On a recent afternoon, the aroma of homemade mashed potatoes filled the zoo's kitchen. The meal was for one of the animals that enjoyed variety at lunchtime.

And, honoring the zoo's namesake, visitors can purchase air-popped popcorn to share with some of the farm and domesticated animals that have less-rigid diets.

Beyond helping animals in need, Bergmann says that the zoo has a larger mission.

"I always hope, and I always think, [that visitors] walk out of here with more compassion for animals than they walked in here with," he says. "I always thought that was a [large part] of our mission, that we would change the minds of people to have more compassion for animals."

While he seems to have found his dream job, Bergmann says he has trouble with one aspect of his work: saying goodbye to the animals that die.

Sonny, an elephant, had been brought to the United States from Zimbabwe to be trained for circus work. After he resisted his training, he was sent to a New Mexico zoo, from which he escaped several times.

Rather than putting him down, in 1989 the zoo sent a letter to other facilities across the country to see if anyone might give a new home to the troubled creature.

"We were the only one that raised our hand," Bergmann says.

It took extensive care and much training, but Sonny finally adapted to his new surroundings at Popcorn Park and lived there a dozen more years, dying in 2001.

A local funeral home donated its services to host a ceremony for Sonny, and Bergmann delivered a eulogy.

"He didn't belong here," he said, remembering his friend. "All we did was keep him company when he was here."

For Bergmann, it was bittersweet to see Sonny leave Popcorn Park.

"It is very sad that he is not with us any longer," Bergmann says, holding back tears as he adds a comforting thought. "But he is with his herd again."

Helping animals

For more information on Popcorn Park, and for details on how to donate to the zoo or sponsor specific animals, visit www.ahscares.org or call (609) 693-1900.

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations worldwide. Projects are vetted by UniversalGiving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause.

Below are three opportunities to help animals, selected by UniversalGiving:

• The San Francisco Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals provides lifesaving veterinary care for homeless animals before placing them for careful adoption. Project: Provide urgent care for a homeless animal.

• Greenheart Travel is a site for conservation and community-development projects around the world. Project: Volunteer at an animal rescue center and eco-reserve in Costa Rica.

• EcoLogic Development Fund helps conserve and restore forests to preserve wildlife habitats. Project: Preserve a biological corridor in Honduras.

• Sign up to receive a weekly selection of practical and inspiring Change Agent articles by clicking here.