Glenn Paige's simple idea: a 'nonkilling' world

After a flash of inspiration Glenn Paige wrote a book on 'nonkilling,' and now his concept is gaining momentum worldwide.

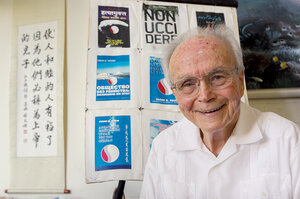

Glenn Paige, a former political science professor, established the Center for Global Nonkilling and inspired a worldwide movement.

Eugene Tanner/Special to The Christian Science Monitor

Honolulu

People who have seen "Hotel Rwanda" (2004) or documentaries about the 1994 genocide in Rwanda may be surprised to learn of the U-turn that the Central African country has made since then.

The turnaround is visible at the Glenn Paige Nonkilling School in the village of Kazimia in Congo, a nation that along with Rwanda has experienced war, genocides, and political violence. (There have been an estimated 6 million deaths in Rwanda and Congo in the past 20 years.)

In the school, more than 200 pupils, who have been affected by war, disease, or abandonment, learn about "nonkilling" in a simplified version of Dr. Paige's book "Nonkilling Global Political Science," which has been translated into Swahili. Located near Lake Tanganyika, the school offers breakfast, health care, and clothing to its students.

Beyond the school, trainers also have used Paige's translated book to explain its main ideas to unschooled adult villagers. The concept was "new and revolutionary," says Bishop Mabwe Lucien of the Pentecostal Assemblies of God churches in Congo. "Nobody in the region had heard these ideas."

Among the 1,100 participants in the training program, Bishop Lucien says, "the hands of assassins were lifted to renounce killing." The trainers, members of nonprofit groups associated with the Center for Global Nonkilling–Great Lakes Africa, founded by the bishop, spread the word to people in 1,100 villages and towns, distributed 4,500 books, and persuaded 30,000 others to work for a nonkilling society, causing the level of violence to drop, he says.

"The impact of the teachings of Prof. Glenn Paige is enormous," the bishop adds. "They have transformed the region."

The school is named after Paige, a cherub-faced retired political science professor who lives half a world away in Honolulu. His influential work began far from African villagers in 2002, when he published his book.

In it he describes a "nonkilling world" as one without killing, threats to kill, or conditions conducive to killing – and one in which there is no dependence on killing or the threat of killing to produce change.

Leading university presses, including the one at his alma mater, Princeton University, declined to publish the book.

"Thank goodness," Paige said recently over lunch at a Korean restaurant in Honolulu. "These publishers would get involved with royalties and copyrights, and it would never have spread out as it did."

Instead, Paige posted his book on the Internet, giving it away free of charge in a version that anyone can download from the website of the Center for Global Nonkilling (www.nonkilling.org), which he founded. The book can also be printed on demand through Amazon.com and other online book retailers.

Though the Web has permitted easy distribution of the book, the big reason for its rapid spread is the nonkilling concept itself, Paige says. In his view, "The logic of killing is running out of steam."

Within five years the book was translated into 15 languages, including Arabic, Russian, Hindi, French, Portuguese, and Spanish. Today it is available in 30 languages.

Chinese-born Maorong Jiang, an associate professor of political science at Creighton University in Omaha, Neb., is a key advocate of Paige's book and teachings. Dr. Jiang has founded the university's Asian World Center and its affiliate, the Nonkilling Consortium International. "The future generations are our destiny," he says. "Do not kill them before they are even born."

The book has begun to influence academic thinking across numerous disciplines. Paige has encouraged scholars to question the "assumption that killing is an inescapable part of the human condition and must be accepted in theory and practice." More than 700 scholars in 300 academic institutions in 73 countries have joined in 19 disciplinary research committees to look at nonkilling.

"These scholars are contributing to a scientific paradigm shift from acceptance of killing to discover and apply nonkilling knowledge," says Joám Evan Pim, director of the Center for Global Nonkilling. "Glenn made nonkilling a legitimate subject of research."

That paradigm shift has already resulted in books on nonkilling in such fields as anthropology, economics, engineering, geography, history, linguistics, and psychology. All are available for purchase in print or free download at the center's website.

"You cannot understand or achieve something by ignoring it," says University of Hawaii anthropology professor Leslie Sponsel, who calls on natural and social scientists to study nonkilling and nonviolence intensively and systematically.

The work of the nonkilling center builds on the UNESCO Charter declaration of 1945, which states that "since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defenses of peace must be constructed."

Paige and his center have held nonkilling institutes or forums in the Balkans, Brazil, Haiti, India, Nigeria, Germany, and Africa.

Paige's book was translated into Filipino in 2004, and five years later a citizens' organization called a Movement for a Nonkilling Philippines sprang up. It has proposed that the national government establish a Philippine Index of Killing and Nonkilling to collect information about how many people have been killed, and how and why they were killed.

"With this information we would learn more [about] how to prevent, reduce, and even stop some of these killings," says Jose Abueva, a cofounder of the movement and former president of the University of the Philippines. He is also promoting a bill in the Philippine legislature that calls for declaring "a Peaceful and Nonkilling Philippines as a National Goal" and for establishing a Department of Peace and Human Security.

The concept of nonkilling has three strengths, Paige says. First, it is measurable. It focuses directly on stopping the taking of human life, unlike the more abstract terms of "peace" or "nonviolence." Nonkilling also calls for no specific type of society, government, or laws, but instead urges individuals and institutions worldwide to create their own interpretations of nonkilling. And nonkilling draws its inspiration and strength from a wide variety of religious and humanist sources that all speak of a respect for life.

Paige is likely the first person to use the word "nonkilling" in the title of an English-language book. The word is not yet found in an English-language dictionary. But it has already made its way into the Oxford International Encyclopedia of Peace; the Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, and Conflict; and UNESCO's Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems.

It is also found in the Charter for a World Without Violence adopted by the Nobel Peace Laureates in 2007 at their world summit in Rome. These illustrious peacemakers called on "all to work together towards a just, killing-free world in which everyone has a right not to be killed and the responsibility not to kill others."

Paige, a Korean War veteran and a onetime military "hawk," remembers the moment his thinking changed in 1974. "It was like an electric current surging from the tips of my toes right up through the top of my head," he says. "Three silent words came to me: 'No more killing.'

"And then I wondered, 'Now what am I to do?' " That question launched his quest to make a nonkilling world real.

In 2002, the World Health Organization published a comprehensive summary of violence around the world. Both it and Paige's book, issued the same year, conclude that human violence is preventable. And the Center for Global Nonkilling is now a partner of the World Health Organization's Violence Prevention Alliance. Both groups call for more research, resources, programming, and action against killing.

"We are going to eliminate human killing on the globe just the way we put a person on the moon," Paige says.

Ways to work for peace

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations worldwide. Projects are vetted by Universal Giving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause.

Below are three groups selected by UniversalGiving that promote peace, including through voluntary service:

• Volunteers for Peace offers opportunities for voluntary service. Project: Choose from more than 3,000 volunteer service projects worldwide.

• Global Citizens Network builds cross-cultural understanding and connectedness through immersion experiences. Project: Volunteer at a center for peace.

• Asia America Initiative promotes peace, social justice, and development in impoverished communities. Project: Support peace through education by giving to help keep a child in school.