William Whittenbury employs his 'can do' spirit to save an endangered porpoise

Fewer than 100 little vaquita porpoises are left in the Gulf of California. California teenager William Whittenbury aims to save them.

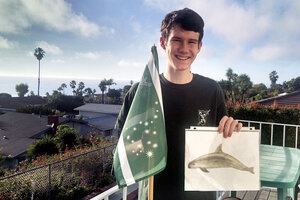

SAVE THE PORPOISE: William Whittenbury is on a one-teen crusade on behalf of the vaquita, a rare species found in the northern Gulf of California.

Courtesy of Beth Whittenbury

Los Angeles

The vaquita porpoise, a rare species found only in the northern Gulf of California, is on the verge of extinction.

Seventeen-year-old William Whittenbury is leading the fight to save it.

Spanish for “little cow,” the vaquita (aka the cochito, the desert porpoise, or the Gulf of California harbor porpoise) is less social than other dolphins and tends to live in shallow, murky lagoons along shorelines. Snub-nosed – without the long proboscis of TV’s Flipper – it is the world’s smallest cetacean, measuring about 5 feet in length. About half its population has been killed in the past two years, entangled in the fishing nets of both the shrimping industry and illegal poachers hunting the endangered totoaba bass.

The best estimate is that there are 97 left. “The vaquita is in imminent danger of extinction,” the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA) recently reported.

Enter William, a suburban California teenager who spends most of his free time on issues such as saving the vaquita and on other volunteer projects – and not with the usual high school activities, such as sports.

“Conservation needs next-generation leaders with an optimistic ‘can do’ worldview,” says Dr. Barbara Taylor, a research fish biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service. “William heard about vaquita at a local aquarium and decided he could do something to make a difference ... and he has.”

William has been leading the charge to trumpet the problem, raise money, and pressure the Mexican government to use other kinds of nets and crack down on poachers. To further his efforts he started a club while in middle school, developed a website, and speaks at other local schools.

His organization, the Muskwa Club, now has 49 chapters in six countries (the United States, Finland, Germany, Austria, Mexico, and the Netherlands); its members range in age from elementary school through college. The Muskwa Club wasn’t founded to work on the vaquita issue but adopted it as a project in 2012 about two years after the club was started. It recently became a tax-exempt nonprofit corporation.

“As humans in a position to effect change, it is our responsibility to make sure that another cetacean species doesn’t disappear from the earth,” William says. “My goal is to get the word out about the vaquita’s plight. The more people [who]know about it, the closer we get to saving the species.”

William says he feels strongly that no matter how discouraging a situation may seem to be, it’s important to never stop working toward a solution.

“There have been many success stories in the past of species bouncing back from the brink,” he says. “I have no doubt that the vaquita can do just that.”

Dr. Taylor, who also advises CIRVA, agrees.

“Many of the world’s most serious problems, from losses of rare species like vaquita to global climate change, seem like hopeless causes to most people,” she says. “We need the ‘Williams’ to defeat this self-fulfilling defeatist attitude or else the world will be a much poorer place.”

William came up with the idea of a “Vaquita Blanket Challenge,” which he explains in a YouTube video that has gone viral. The challenge simulates the capture of a vaquita in a net by asking viewers to escape from being rolled up in two blankets in 97 seconds.

“This challenge gives the participant the visceral feeling of what it must be like for a vaquita to get stuck in a net and drowned before it can get back to the surface for air,” William says.

While saving the vaquita is the Muskwa Club’s biggest project, it has undertaken a number of other activities. Its members are building an unmanned aerial vehicle to count Pacific gray whales, have entered the Jet Propulsion Laboratory Invention Challenge for the past three years, conduct educational field trips and family social events, and lead a student speaker series called Muskwa Amplified (a sort of TED Talks.)

William has also been promoting a better fishing net – called the safe net project – that the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) developed with the Mexican government, which has donated $100 million to the effort. As added assurance, William says, Mexican or US aircraft, such as drones, should be employed to help stop illegal fishing.

Members of Muskwa say William inspires them by setting a tireless example. “He is an incredible and driven guy, and the Muskwa Club and the vaquita are lucky to have him,” says 14-year-old Aidan Bodeo-Lomicky, who has helped William staff dozens of vaquita awareness tables and “directly educated thousands of individuals.”

Even though Mexico has banned the use of gill nets in the vaquita refuge in the northern Gulf of California, illegal use of gill nets has accelerated in recent years because of soaring demand for a rare species of marine fish called the totoaba, especially among the Chinese.

The totoaba was listed as critically endangered in 1996, and its sale is banned under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. The swim bladder of a totoaba can fetch $10,000 to $14,000 because of its purported medicinal properties.

In large part because of totoaba fishing, CIRVA concluded in its most recent report that, unless things change, the vaquita will be extinct by 2018.

“What’s amazing and sad about this story is that the vaquita itself is just collateral damage in this,” William says. He has joined in calls for greater enforcement of existing laws as well as efforts to spark alternatives to gill-net fishing in the region.

Apart from large and well-known organizations such as the WWF, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, and Mexican and US government agencies and committees, the Viva Vaquita Coalition is the main group of organizations dedicated to saving the vaquita. Members include the Cetos Research Organization, the Oceanographic Environmental Research Society, the Intercultural Center for the Study of Deserts and Oceans, parts of the American Cetacean Society, Save the Whales, vlogvaquita.com, and the Muskwa Club.

Many noncoalition organizations also support the effort to save the vaquita, including a number of aquariums in the US and abroad.

At its 2012 meeting, CIRVA estimated that about 200 vaquita remained in the wild. Since then, about half of them are thought to have been killed in gill nets, leaving fewer than 100 now.

“The vaquita will be extinct, possibly by 2018, if fishery by-catch is not eliminated immediately,” says the latest CIRVA report, issued last July. “Therefore, CIRVA strongly recommends that the Government of Mexico enact emergency regulations establishing a gillnet exclusion zone covering the full range of the vaquita – not simply the existing Refuge – starting in September 2014.”

Since past enforcement efforts have failed and illegal fishing has increased throughout the gulf, ending illegal fishing is no longer enough, William says. All gill-net fishing must be eliminated, he says, and regulations must prohibit fishermen from using or transporting gill nets within the exclusion zone.

CIRVA further recommends that all available enforcement tools, both within and outside Mexico, be applied to stopping illegal fishing, especially the capture of totoaba and the trade in totoaba products. It also wants increased efforts to introduce alternatives to gill-net fishing within the exclusion zone.

Though still only a teenager, William plans to press on, alerting people to how they can play their part in making sure that all the above happens.

• Learn more at https://bit.ly/MuskwaClub.

How to take action

Universal Giving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations around the world. All the projects are vetted by Universal Giving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause. Below are groups selected by Universal Giving that help protect wildlife around the world:

• Osa Conservation helps protect the globally significant biodiversity of the Osa Peninsula in Costa Rica. Take action: Help to restore the rainforest.

• In Defense of Animals-Africa provides sanctuary for chimpanzees orphaned because of the illegal bush meat trade in Cameroon and campaigns to save the remaining wild chimpanzees and gorillas. Take action: Volunteer to help care for young chimpanzees.

• Greenheart Travel provides cultural immersion programs that change lives and empower local communities. Take action: Take part in an Amazon environmental sustainability project in Peru.