She’s turning schools around, at high speeds

Tiffany Anderson, who arrived in Topeka, Kan., in July to be superintendent of the public schools, is making a name for herself as one of the best at standing up for the neediest students.

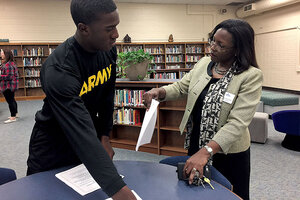

High school senior D’Andre Phillips talks with Tiffany Anderson, superintendent in Topeka, Kan., at a college mentoring program.

Wendi C. Thomas

Topeka, Kan.

This story was originally published at a longer length in the Monitor’s EqualEd section. Click here for that version.

Tiffany Anderson doesn’t have an appointment with the park ranger at the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site in Topeka, Kan.

That doesn’t keep Dr. Anderson, the city’s new school superintendent, from hovering outside his office while the ranger talks to a woman who’d stopped by.

“I’m going to give her a few more minutes. Then I’m going in,” Anderson says.

And she does. She deftly ushers the ranger’s guest out and does what she does best: mine every contact on behalf of Topeka’s 14,000 students, most of whom come from low-income families.

She knew the ranger could put her in touch with the local black nurses association, so she could connect the group to high school seniors interested in health-care careers.

If securing resources for the neediest students is a puzzle, Anderson does more than fit the pieces together. She creates pieces where none exist. This is the challenge of the modern public school superintendent, and Anderson, who has turned other districts around, is making a name for herself as one of the best.

“She epitomizes what we like to talk about – superintendents really being champions for children and public education,” says Dan Domenech, executive director of the American Association of School Administrators.

“You have to have the community behind you – the business community, parents, people who don’t have children in school,” he says. “You can’t be a lone ranger on this job and succeed.”

Kansas is among 31 states that spent less per student in 2014 than they did in 2008, according to a 2015 survey by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Last February, the Kansas Supreme Court ruled that the state’s education funding formula “creates intolerable, and simply unfair, wealth-based disparities among the districts.”

No public schools, the high court said, would open for the 2016-17 school year unless the formula was fixed. And it was, during a special legislative session just weeks before Anderson arrived in Topeka.

“Kansas has underfunded schools for many years, and it’s anticipated that there will be another budget cut because revenue in Kansas has been declining,” Anderson says.

“At the end of the day, I even see that as an opportunity,” she says. “There are never disappointments. There are opportunities and challenges, and if those weren’t there, why would they need you?”

An earlier job near Ferguson, Mo.

Anderson arrived in Topeka in July after four years as superintendent for the once-underperforming Jennings School District in Missouri. That 2,500-student district borders Ferguson, which erupted in 2014 after a white police officer shot and killed Michael Brown, a black 18-year-old.

The challenges in Jennings were many. The majority-black district faced a $1.8 million budget deficit after years of budget cuts. Its state accreditation was at risk; it met just 57 percent of state standards. More than 90 percent of the students qualified for free or reduced-price lunches.

Anderson cut central office staff to shore up finances and saved money through attrition. To bring in support the district couldn’t afford on its own, she partnered with a food bank to open a food pantry and with Washington University to open a health clinic.

Anderson noticed the lack of laundromats in poorer neighborhoods. Washers and dryers were installed in each school; in exchange for an hour of volunteer work, parents could do a load of laundry. And she pushed to turn an abandoned building into a home for students in foster care.

When Anderson left, the district’s budget was in the black, state accreditation was firmly in place, and its schools met 81 percent of state standards. “Even though we didn’t have a lot of resources, we had a lot of will and we had a lot of skill,” she says.

The distance from low-performing district to a top-notch one is far shorter in Topeka. Still, Topeka’s graduation rate and ACT and achievement test scores lag behind the state averages.

Here 40 percent of the students are white, 30 percent Hispanic, and 19 percent black. Three-quarters of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunches.

Anderson inherited a $205 million budget that doesn’t include enough money to meet the recommended 1-to-250 counselor-student ratio. Instead it’s 1 to 500.

That translates to the sort of class-based inequity Anderson and school board members want to root out.

“We’ve talked equity for many, many years,” says longtime Topeka school board member Janel Johnson. “We often think equity means equality, but [with] the understanding that equity means that those who need the most get what they need,... then we can move forward with everybody.”

Anderson, Ms. Johnson says, doesn’t see equity as a buzzword but as a North Star, the guiding light for every choice the district makes.

At the first mentor meeting

The district may not have enough counselors, but it does have a few dozen people who work in the central office. So the entire central office staff was invited (think of it as an offer that couldn’t be refused) to mentor a high school senior and make sure he or she has a postgraduation plan.

“Never ever have we had such a large contingent of the [district office] staff ... come over and be matched with the students,” says Beryl New, principal at Highland Park High. “That was her idea.”

For the first mentor meeting, Anderson arrives at Highland Park in her signature outfit – a church-appropriate suit with skirt, plus white ankle socks and white tennis shoes. She enters the library, where about 20 central office staff members sit with their seniors.

Anderson, a mentor herself, joins 17-year-old Alexandria Williams. Although Alexandria plays three sports, she hasn’t considered playing in college. “I don’t know if I’m good enough,” Alexandria confides.

“Why would you say that?” Anderson asks. There’s a cost to register for the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s clearinghouse, Anderson says, “but we’ll take care of that.”

Alexandria mentions a classmate who wanted to play football, but didn’t have a way to get home after practice.

Anderson sits up straight. This is an equity issue: Students without transportation are cut off from extracurricular activities that could help keep them in school and even get them a college scholarship.

“I have more homework,” Anderson says mostly to herself. “Things that need to be addressed and fixed.”

Her inspiration

Anderson’s uncompromising commitment to equity is inspired by her children, now both in college. If it’s not good enough for them, it’s not good enough for her students.

Although she has an apartment within view of the State Capitol, Anderson makes the 60-minute drive from her home in Overland Park, Kan., each weekday. A New International Version of the Bible rests on the console between the front seats of her SUV.

Anderson’s parents are preachers, and at a lunch gathering for the Topeka YWCA, she segues from teacher to evangelist.

“Imagine if poverty did not impact young people,” she says to the capacity crowd. “Imagine every child had a home to go to, and food and security was not an issue.”

“Really, you don’t have to imagine it. If we just wake up and change how we address issues, change how we think and realize that collectively, we literally can change systems,” she says.

Topeka’s first black female superintendent has been gathering admirers on the local speaking circuit. The annual State of the District breakfast typically draws about 200 people and raises about $20,000, says Pamela Johnson-Betts, executive director of the Topeka Public Schools Foundation. With Anderson as the speaker, the crowd topped 350 and raised $35,000 for schools.

“In the nine years I’ve been here, this is the first year we’ve sold out,” says Ms. Johnson-Betts. “The community has received [Anderson] well because she wrapped her arms around the community.”

How to take action

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations around the world. All the projects are vetted by UniversalGiving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause. Below are links to three groups that support learning:

Shirley Ann Sullivan Educational Foundation improves the quality of life for children by providing education and lobbying for their protection from exploitation. Take action: Send a child to school.

BiblioWorks gives communities in need tools and resources to develop sustainable literacy programs. Take action: Provide new picture books for a rural library.

Daraja Education Fund makes it possible for Kenyan girls to receive a secondary education at a boarding school free of charge. Take action: Help sponsor the freshman class.