Can the U.N. avert a Kirkuk border war?

The United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq is expected to unveil a plan in May that it hopes will lead to a compromise over contentious land issues in oil-rich northern Iraq.

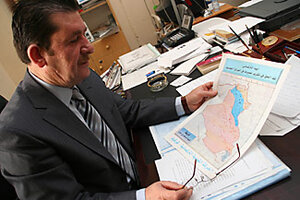

Homeland: Ali Mahdi, a Turkmen deputy in Kirkuk, points to a map of the historic Turkmen community in Iraq.

Sam Dagher

KIRKUK, Iraq

Kirkuk provincial council head Rizgar Ali says one proof of the province's "Kurdishness" is in the maps.

Several maps dating from the Ottoman and British colonial eras hang on his office walls showing the city of Kirkuk at the heart of a Kurdistan that spans parts of Iran, Syria, and Turkey. A 1957 map shows Kirkuk Province's original border prior to it being renamed Tamim and then altered by Saddam Hussein's Arabization policy.

But Ali Mahdi, a Turkmen leader here, has his own maps. His show the city of Kirkuk at the heart of Turkmeneli: the supposed home of Iraq's ethnic Turkmen population.

The vastly different ways that Iraq's ethnic groups view this province and its capital city, Kirkuk, illustrate the deep-rooted, complex, and potentially explosive issue of its status and the ongoing debate over Iraq's internal borders. In Kirkuk, the issue was supposed to have been decided by a constitutionally mandated referendum to take place by the end of 2007. The vote is delayed until June.

In the meantime the United States is using its leverage with all sides – Kurds, Turkmen, and Arabs – to keep the situation from blowing up into an all-out war for control here as the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) works on a plan to broker a peaceful solution to the status of the province that is the home of northern Iraq's oil industry.

In addition to Kirkuk, the UNAMI plan is looking at other disputed areas spanning an arc that is almost 300 miles long and stretches from the city of Sinjar in northwest Iraq to Diyala Province in the east.

"We do put it as a very top priority of ours to deal with this issue ... now we believe that UNAMI's efforts have the best chance of getting at a stable and secure resolution to this issue," says a US diplomat in Baghdad who spoke on condition of anonymity due to embassy requirements.

According to the US diplomat and Muhammad Ihsan, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) minister on the national committee dealing with Kirkuk, UNAMI's efforts involve suggestions for resolving the fate of at least four contested areas in the hopes of leading to a greater compromise on Kirkuk Province territories on which each ethnic group has claims. Its plan is expected to be announced in mid-May.

"If you start with some of the areas that are less controversial ... you might have some processes in place that have buy-in from all the sides involved, so you have an easier way of getting at ultimate resolution on the boundaries," says the US diplomat, adding that UNAMI's proposed solutions look at how commerce and the sharing of water resources would be affected in the process of border resolution.

"We are looking for ways to compromise. Some areas are soft, some areas are hard," says Mr. Ihsan, using the terms "soft" in English to describe the areas that are overwhelmingly made up of one of the three ethnic groups and "hard" being the more mixed and contentious areas.

He says the KRG would be open to working out within the UNAMI-administered process "power-sharing formulas" in places where Kurds are present but do not make up the majority.

In return, he says, the KRG would demand that areas that are overwhelmingly Kurdish and are now de facto under the control of the two main Kurdish parties be annexed to the KRG. As for the city of Kirkuk, he says the KRG is willing to have its fate decided through a referendum but no later than the end of 2008.

Kurdistan's Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani says that although his government is determined that the city of Kirkuk and other contested areas become part of its semiautonomous KRG that does not mean it would not be willing to have other communities – namely the Arabs and Turkmen – be represented in the local administration.

"We are ready for power-sharing in Kirkuk," says Mr. Barzani, adding that his government's willingness to have the implementation of Article 140, which calls for a vote on the fate of Kirkuk, extended until June is a sign of goodwill.

But Barzani says the KRG's willingness for compromise does not mean it will give up on the city of Kirkuk. He recounts how his grandfather Mustafa Barzani, considered a Kurdish national war hero, had proposed to Mr. Hussein in 1970 "just do not deny Kirkuk is part of Kurdistan and we are ready for any agreement. He refused and fought us."

For the Iraqi Turkmen Front (ITF), the most militant camp that is supported by Turkey, and many Arabs, Article 140 has expired. The ITF says the only solution now is to declare Kirkuk "a special province" and allow a period of at least 10 years to resolve internal border disputes.

Many Arab leaders here say they are caught between a rock and a hard place when it comes to the Kirkuk question.

"We are like a dog who can't go anywhere because his tail is stuck … we are accused by the Americans that we support the insurgency and if we take part in the political process we are labeled by our own people as agents," says Sheikh Abdullah Sami al-Assi al-Obeidi, a member of the Kirkuk council. He has been the target of three assassination attempts since 2005.

The Arab leaders in Kirkuk, including some of the US supported and funded sheikhs involved in the Awakening movement, or sahwas, against Al Qaeda, held a conference last month to announce that the Kurds are "dreaming" if they think Kirkuk would ever be part of the KRG.

"Kirkuk is for all Iraqis and it will stay that way," says Sheikh Issa al-Jubbouri, who leads a US-funded militia in Zab, southwest of the city of Kirkuk. He says he receives nearly $250,000 each month from the US military.

But as the resolution of the Kirkuk issue drags on, many average Iraqis feel as if they are living in limbo. Almost daily, hundreds of people come to the provincial council office in the hopes of receiving payment from the national committee tasked with implementing Article 140.

Kurds, driven out by Arabization and who have resettled in Kirkuk, receive roughly $8,300 in assistance. Arabs leaving receive double that. But there is still much hardship on both sides.

Bikhal Karim, a Kurd, says that her family fears the potential of more violence and still can't afford to stay in the city of Kirkuk and want to go back to Suliemaniyah, inside the KRG.

"When I get this check cashed we are going back," she says.

An Arab family that has returned to Samarra, in neighboring Salaheddin Province, is also trying to collect compensation. "If they share the oil, we do not have a problem if they [Kurds] take Kirkuk," says Omar Mustafa. But his comment is immediately condemned by other Arabs standing nearby, just one piece of evidence of how difficult it will be to solve the Kirkuk question