Iraq's antiquities garner international attention

In wake of widespread illegal looting, Iraq and Western countries are attempting to better guard ancient cities from smugglers and prevent them from selling the artifacts.

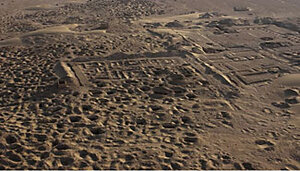

Cultural plunder: Man-made craters in the ancient city of Umma are the signs of illegal looting, which US and Iraq officials are hoping to stop.

Iraqi Board of Antiquities and Heritage

Baghdad and Chicago

Across southern Iraq, large stretches of terrain resemble a moonscape, the earth pocked by dozens of untidy craters.

The man-made holes have been dug as part of the looting of Mesopotamia's archaeological sites that experts say is robbing Iraq of its ancient heritage.

The looting not only funds unscrupulous dealers of artifacts, but also elements of the Iraqi insurgency. Experts say it has dwarfed the high-profile looting of Iraq's National Museum shortly after the US took Baghdad in 2003.

That rampage, carried out by dozens of Iraqis as US troops looked on, resulted in the loss of an estimated 15,000 museum pieces, ranging from statues to clay tablets. More than 6,000 of those items have been recovered as Iraq continues to try to bring back pieces that have made their way to foreign markets.

But the silent destruction of the vestiges of some of the world's earliest civilizations proceeds nearly unabated, museum experts say, and could prove damaging to the chronicling of Iraq's storied heritage.

"The looting of ancient sites is an old problem, of course, but this phenomenon has accelerated since the invasion of Iraq and the general insecurity that has left so many sites with no protection," says Qais Hussein Rashid, director of research and antiquities excavations for Iraq's Board of Antiquities and Heritage. "We feel we are losing many of the keys to our past and the many pieces that together make up our heritage."

Iraq has more than 12,000 significant archaeological sites, dating back to 2500 BC at Kish, near ancient Babylon.

For all these sites the government of Iraq employs only 1,200 guards, leaving many gaps. "We have easily 11,000 archaeological locations with no protection," Mr. Rashid says.

Another challenge is that many of the most prized artifacts the looters pull from the ground are no bigger than a wallet and easily fit into a smuggler's pocket, such as small clay cuneiform tablets on which a king's inventory or a family's history was kept before the advent of parchment.

When rolled in a soft material like putty, the seals embossed a picture depicting some aspect of the owner's identity: an officer's role in a major battle or the duties of a royal scribe.

"In and of themselves these are distinctive Mesopotamian artifacts, but they tell us so much less as looted pieces than if the full context of their excavation had been recorded," says Geoff Emberling, director of the University of Chicago's Oriental Institute Museum. "Were they found in a ruler's palace or an ordinary house, in what room, how deep in the ground? With looted pieces, we lose all of this."

An exhibit on the pillaging of Iraq's heritage, titled "Catastrophe!" is currently running at the Chicago museum, along with seminars from Iraqi experts and delivered to US troops deploying in the region.

"The destruction of Iraq's past has the potential of being one of the longest-lasting legacies of the US presence in Iraq," Mr. Emberling says. "It really seems incumbent upon us to do what we can to stop that process."

At the Baghdad offices of Iraq's Antiquities Board, Rashid looks over trays of the small seals. He says all but about a dozen were objects looted from archaeological sites since the invasion, and they are part of 701 smuggled items returned to Iraq from neighboring Syria in April.

"It is a sign that we are having some success" in raising awareness and developing cooperation with transit countries for the smuggled artifacts, he says, "but we have to do much more."

In the face of criticism over the 2003 museum looting, the US is taking steps to help Iraq address the looting of sites and to at least begin addressing the challenge of preserving its cultural heritage. Archaeological site guards have been sent to the US for training in patrolling and looting-detection methods, the Department of Justice is investigating smuggling cases with Iraq's Interior Ministry, and the State Department has awarded grants for Iraq to purchase some site-monitoring equipment. The US military, also trained in cultural sensitivity, now keep an eye out for illegal activities as they carry out their patrols.

Specialists say Iraq is taking a number of important steps, like developing its corps of site protection guards, but they are realistic about how much the country can do. Iraqi and US officials acknowledge that preservation of cultural heritage falls low on the priority list of a country at war and facing daunting reconstruction.

The US military has pulled out of a camp it established after the invasion at the famous Babylon archaeological site, a presence that was particularly irritating to Iraqis sensitive to a foreign occupation. A US-Iraq working group has been set up to develop and implement a restoration plan for the site.

At Kish, where the US kept a radio transmitting station until 2005, soldiers from a nearby base now keep a watchful eye on the site of the ancient kingdom. American soldiers regularly patrol in the area of Kish. "At the site now, there are no signs of looting," says Diane Siebrandt, an archeologist and cultural heritage liaison for the US Embassy in Baghdad. "It's really one of the good-news stories of Iraq."

Still, she says complex issues like site restoration, as in the case of Babylon, won't be easily resolved. One challenge is that many antiquities experts fled Iraq's violence. "There are still a lot of archeologists left in Iraq," says Ms. Siebrandt, "but you need people who are specialized in repairing mud-brick structures, it's really a very specialized skill."

Iraqi officials point to the growing assistance they are receiving from Western countries as an encouraging sign. Rashid says the first group of US-funded specialists for Babylon's restoration began training in Jordan on May 2.

And he says a loose network of watchdogs is also at work around the world to help stop Iraq's pillaging. Recently he received frantic e-mails from a source of his in New York reporting plans for a private sale of ancient artifacts – many of which showed telltale signs of originating from southern Iraq.

Back in Chicago, Emberling says evidence turned up by US and Iraqi officials that the sale of looted artifacts is funding insurgent activities is a good, hard-nosed reason for efforts to stop the plundering. But not the only one: "This historical record the looters destroy is Iraq's heritage, and it is the heritage of all of us."