Is Iran prepared to undo 30 years of anti-Americanism?

As Obama spells out aims to engage with Iran, the Islamic Republic debates whether to step away from decades of hatred for the 'Great Satan.'

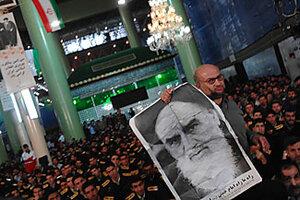

Father of the revolution: An Iranian man held a poster of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini on Jan. 31 at a gathering south of Tehran.

Scott Peterson/Getty Images

Tehran, Iran

"On that day when the United States of America will praise us, we should mourn," said Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, leader of Iran's 1979 Islamic Revolution.

His words so captured the uncompromising anti-American ideology here that they were painted like a billboard across the old US Embassy wall in Tehran, standing for years as a message of defiance to the West.

Today the quote is gone, recently painted over as if to signify a softening of Iran's hard-line rhetoric. But as President Obama spells out his wish to engage with Iran, is the Islamic Republic – which marks its 30th anniversary next week – really ready to set aside decades of official hatred for the "Great Satan"?

That is the debate now swirling across Iran, where leaders have been sending mixed signals as they anticipate an unprecedented public effort by Washington to reach out to its archrival.

[This is Part 2 in a two-part package on Iran's view of America under Obama. To read Part 1, 'Iranians wary of Obama's approach,' click here.]

Call for global respect

Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad Thursday called for a new level of global respect: "Bullying powers should learn how to speak correctly and be polite so Iran's cultured and peace-loving people listen to them," he told a rally in the northeast city of Mashad. "Iranians are logical people … and welcome anyone who offers a solution to problems of the world."

Analysts agree that only Supreme Leader Ayatollah Sayed Ali Khamenei can make a final decision on US ties – and justify it to ideologues that have despised America for a generation.

But not all agree that Ayatollah Khamenei can bring himself to do away with such a useful enemy. Last November he said not a day had passed "in which America has had good intentions toward Iran," and that the US-Iran problem is "like a matter of life and death."

"The Leader is a very rational person [and] wants to control the country and respond to reality," says Amir Mohebian, a conservative editor and analyst. "When the US sends a hard signal, the Supreme Leader is very hard. If the US sends a soft signal, he is very soft. We balance ourselves with our partner."

While Iran boasts the most pro-American population in the region, any substantive talks with the US are a big step for a regime that still chants "Death to America" at rallies.

"Some people think this is the time to solve the problem with the US in a balanced way," says Mr. Mohebian. "But others think the hostility against the US after 30 years is a main element of our identity, and if we solve it we will dissolve ourselves."

Mixed signals from Tehran

The mixed signals from Tehran can bolster either view. The firebrand Mr. Ahmadinejad wrote an unprecedented note of congratulations to Mr. Obama just days after the US election, noting high expectations for change. Despite fierce anti-Western rhetoric and verbal attacks against the US, Ahmadinejad has reached out more than any of his predecessors, telling Americans the US could be a "great friend" of Iran.

But this week an official representative of Khamenei said that confronting the "arrogant policies" of the US and Israel were "red lines" for Iran.

"Opposing the Zionist regime and defending oppressed people are among the pillars of the Islamic revolution and Iran and America's relationship will not change because of Obama taking office," said cleric Ali Maboudi, in a Fars News Agency report quoted by Reuters.

American officials are deciding how to approach Iran – and when, considering Ahmadinejad is up for reelection in June – to maximize chances of success on issues from Iran's nuclear ambitions to its regional role. The US has long labeled Iran the "premier state sponsor of terror" for supporting Hezbollah and Hamas and accused it of causing US deaths in Iraq by supporting Shiite militias.

Past efforts have failed, and numerous secret contacts yielded little. Significantly, analysts say Iran still smarts from being included in President Bush's "axis of evil," after giving critical help to the US during and after the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan.

"The main issue here is 'What will be the answer?' " says a Western diplomat in Tehran. "The Iranians are very confused. The Americans are still discussing the best strategy, but they know what they want. Here, I am not so sure. Iran has been a revolutionary state for 30 years and needs a crisis, an enemy to survive.

"If the archfoe is not the archfoe, then what?" asks the diplomat. "If Obama were to officially make a request tomorrow, there would be shock here…. They want [to engage] – it's clear – but the question is how to do this without losing face."

Already Ahmadinejad has broken the anti-US taboo and analysts say Iran now has certain expectations in return. State Department officials have been drafting letters to break the ice, and are debating whether the US should reach out before Iran's election. But such a move could give Ahmadinejad a boost over challengers like former President Mohammad Khatami, a reformist who won elections in 1997 and 2001 by a landslide but was still unable to break the US-Iran deadlock.

Window of opportunity before Iranian elections

In Iran, some argue that if the US does not send a message before the Iran election, it will show a US preference in the vote and be seen as meddling. Others point out that only Ahmadinejad has the rightwing gravitas to reassure hard-liners.

A swift American move may produce better results, says Mohebian, with a "short, polite" letter to Ahmadinejad from Obama, thanking him for his note and "hoping to make a new reality."

"But the main letter – to solve the problems – should be sent to the Leader," says Mohebian. This letter should acknowledge past historical grievances – such as the CIA-orchestrated coup in 1953 – and suggest: "It's better to forget the past. The Islamic Republic is a reality. We want a new future," he says.

"After that you will see the situation change – not immediately, but gradually over two years," says Mohebian. During that time, both sides would have to commit to new policies. Khamenei could portray the change as one of strength, not weakness, he says.

But is such a scenario possible? Even those close to ruling circles caution that Iran's reaction will depend upon US actions. And they can't predict how far the Islamic system is willing to budge.

"The first thing Iranian leaders need is to be convinced the US is not after regime change," says a veteran analyst in Tehran. The regime "wants" to engage, though "only someone deep in the religious establishment can do it and Ahmadinejad has the credentials. But he also must keep his revolutionary image and rhetoric."

"I would really like reformists to rule the country – it's better," says this analyst. "But in these crucial issues, they will be crippled if they try rapprochement…. If strange things happen and Ahmadinejad and Khamenei are doing it, they can't stop [hard-line reaction], but can convince them to go along."

Yet there is plenty of room for doubt, says a reformist political scientist in Tehran: "They rule the country based on their opposition to the US. If they change there is no basis for their legitimacy," he says. "Ahmadinejad is very, very interested in resuming negotiations with the US, but the leader does not allow it [because] anyone who does that will be a big hero in Iran."

• Part 2 of two. Yesterday: Iranians remain wary of Obama's approach.