Neither liberal nor Islamist: Who are Libya's frontrunners?

Libya's National Forces Alliance has claimed the lead as election results roll in. The big-tent coalition appears headed for victory, but it's still unclear what its goals are.

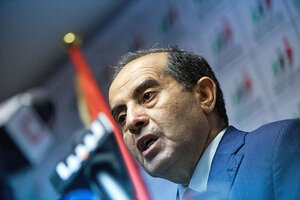

Mahmoud Jibril speaks at a press conference at the National Forces Alliance headquarters in Tripoli, Libya, Sunday.

Manu Brabo/AP

Tripoli, Libya

Two days after Libyans voted in their first elections in more than four decades – a key step toward remaking their country after Qaddafi – many are talking about a possible liberal win in a country long seen as conservative.

Votes are still being counted, but yesterday, the National Forces Alliance coalition (NFA) claimed an unofficial lead in congressional elections, something the two main Islamist groups acknowledged. Now the question is: with NFA leader and former interim prime minister Mahmoud Jibril rejecting both the liberal label and the Islamist, what does the NFA intend? And what do Libyans think it intends?

Two days ago, Libyans voted in their first elections in more than four decades – a key step toward remaking their country after the downfall last year of dictator Muammar Qaddafi. Votes are still being counted, but already Libyans are talking about a possible liberal win in a country long seen as conservative.

Yesterday, the National Forces Alliance coalition (NFA) claimed an unofficial lead in congressional elections, and two main Islamist groups acknowledged the claimed lead. But with NFA leader and former interim prime minister Mahmoud Jibril rejecting both the liberal label and its Libyan opposite, Islamist, what does the NFA intend? And, perhaps as important, what do Libyans think it intends?

As Mr. Jibril tells it, the NFA is classic big tent politics: about 55 diverse parties and 100 individual candidates united to make Libya function after autocracy.

“We’re not an ideological organization,” he told reporters at a press conference last night at the NFA’s headquarters. “We’re a mixture of different parties who have joined hands to rebuild this country.”

For supporters, however, Jibril represents the Libya they want to see take shape: politically centrist, outward-looking, respectful of Islam but not beholden to it.

“I want a modern country, though not too liberal, because we’re Muslims,” says Nairuz Shihub, a young bank employee taking a lunch break this afternoon in the upscale district of Hay al Andalus. She voted for a party from within the NFA party.

“Jibril has a lot of plans for the economy and for education, and he’s not closeminded like the Islamists,” she says.

United by a common goal

A former prime minister in the interim government appointed last year by the National Transitional Council (NTC), Jibril toured Libya for months to meet local leaders, says Faisel Krekshi, the NFA’s secretary general. “The main thing they all have in common is a basic principle: Start building Libya,” Mr. Krekshi says.

The NFA wants to form a unity government with rival groups, including Islamists such as the Justice and Construction Party, a Muslim Brotherhood branch, and the Nation Party.

“This country is 100 percent Muslim; talking about secularism would be stupid,” Krekshi says. “Religion cannot be an obstacle to restarting the country.”

The NFA rejects political Islam. But its manifesto cites Islam as a source of law while pledging respect of other religions and foreigners’ freedom to practice them.

It remains to be seen how votes will stack up in official results expected later this month. Even with a high score, the NFA might splinter or fail to find partners.

Islamists might deem Jibril insufficiently pious, while eastern Libyans might criticize his service in an interim cabinet that some say has favored Tripoli, says Mustafa Fetouri, an independent Libyan academic in Belgium. Easterners have also complained that their region gets only 60 of 200 congressional seats, while Tripoli gets 102.

“That could deny the NFA a majority coalition,” he says. “Or parties could take matters into their own hands and cause trouble in areas like the east and southeast.”

Jibril, meanwhile, called for dialogue with disgruntled easterners and stressed problem-solving over polemics. “Arguments don’t serve the interests of Libyan citizens,” he said.

Jibril's star power

The NFA wants to leave questions of ideology aside to focus on nuts-and-bolts issues. That would be a dramatic break from Mr. Qaddafi’s rule, when Libyans were subject to his shifting interests.

He backed armed groups in the name of anticolonialism, banned political parties in favor of the jamahiriya committee system – his own invention – and as a pan-Africanist lavished Libyan wealth on sub-Saharan governments.

Libya, meanwhile, was neglected. Today many note the contradiction between the country’s vast oil reserves and the shabby state of its roads, schools, and infrastructure.

During Jibril’s press conference, the electricity cut out. He stopped in mid-sentence, the room dark, until staff members started a generator outside. When the conference, ended the audience filtered into the night beneath a giant NFA poster bearing his image.

He stresses that he is one of many partners. Yet star power and a hurried 18-day campaign period has brought him to the fore, says Krekshi.

Many voters on Saturday said they put individual capacities above party affiliation. But for some, association with Jibril was a plus.

“He was one of the first people in the NTC, and we saw him on television more than the others,” says Ms. Shihub.

“We haven’t had time to fully explain our program,” says Krekshi. “But it would be crazy to hide a personality like him. If you have a Ferrari, you go with it.”