With aid groups stretched thin, Syrian refugees provide their own relief

With the number of Syrian refugees in Jordan reaching 10 percent of the Kingdom's population, international and Jordanian NGOs can't meet all their needs.

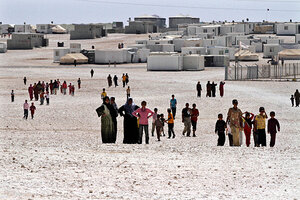

Syrian refugees gather at Zaatari camp near the Syrian border, near Mafraq, Jordan, during a visit by Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida, unseen, Friday, July 26, 2013.

Raad Adayleh/AP/File

Amman, Jordan

As the Syrian exodus continues at a stunning rate, most starkly evident in this weekend's footage of thousands rushing into Iraqi Kurdistan, host countries are overwhelmed. In Jordan, local and international NGOs were caught off guard by the scale of the influx and lack the resources to absorb their numbers. The funding gap is increasingly being filled by independent, ad-hoc aid networks of Syrians living in the Kingdom.

Roughly 515,000 Syrians have been registered or are awaiting registration by the UN humanitarian agency in Jordan – almost 10 percent of Jordan’s population. While the Zaatari refugee camp near the Syrian border has become the human face of the refugee crisis, three quarters of refugees are dispersed throughout urban areas.

About 10 Syrian groups are helping refugee communities in Jordan's major towns and cities, where NGOs face the challenge of a dispersed population.

"In the camps, people are all in one place and it's easier to manage. A lot of funding has gone to the camp so far, but people are scattered across the country – our main objective now is to mobilize our local partners in host communities," says Michele Servadei, deputy representative for Jordan for the UN children's agency, UNICEF.

One of the more ambitious ad hoc operations is run out of a dimly lit basement in Irbid. When Syrian Adnan Abuon arrived a year ago, he despaired at the disconnect between local institutions and the refugees who needed them most.

“So many Syrians in Jordan didn’t know how to access help,” he says. “I started getting friends and neighbors to make a record of Syrians living in Irbid. Now there are more than 20 people working across Jordan, all voluntarily, recording refugees’ details and situations.”

So, partnering with a handful of Jordanian NGOs, Mr. Abuon founded the Syrian Institute for Documenting and Publishing (SIFDAP), which matches the needs of refugees with charities that can help. In the past two months, the organization registered 2,800 fatherless Syrians who qualify for financial assistance. The group’s latest project is geared toward Syrians like Shaher (who asked that his first name only be used), who need medical help but don’t qualify for free treatment at Jordanian state hospitals because their needs aren't deemed urgent.

Shaher had lost feeling in his legs after he was shot while fighting with the rebels' Free Syrian Army. The bullet was removed at a Syrian field hospital and he received treatment for burns in Jordan, but was refused further care.

"The doctor in Amman said I was paralyzed and didn't need any more treatment," he says.

Through physiotherapy sessions coordinated by SIFDAP, Shaher has regained some feeling in his legs. However, the price of the surgery that could help him walk again is prohibitive for the organization. It is searching for additional funding.

The ad hoc aid organizations could also heal some of the deep divisions among Syrians. The Syrian Refugee Relief network has united five Syrians from disparate religious backgrounds through a desire to help the most vulnerable.

"Word spread quickly around refugees in Amman. We became famous!" exclaims Sameer, who joined the group last summer and also requested that only his first name be used.

“We distribute food, mattresses, blankets, cookers, heaters, furniture – whatever people need. It’s not sophisticated, we just respond to refugees’ needs, whether it’s baby hygiene kits for new mothers or money for rent, we try and help the poorest,” he says.

The group hosts fundraising events in Amman and receives contributions through word of mouth and online.

“We’ve had donations from Syrians here, Jordanians, and from Europe. A Spanish company donated a percentage of their wages so we could purchase gas heaters last winter. It’s amazing, these people have never met us but they believe in the work we do.”